|

Julio Cortázar and Michelangelo Antonioni::

‘Blow up and Other Stories’: Cortázar's influence on Cinema

'Blow-Up and Other Stories' is a collection of short stories, written

by Argentinian author Julio Cortázar, who wrote 'Rayuela' (Hopscotch),

reviewed last week. The title story of the collection served as

inspiration for Michelangelo Antonioni's film title 'Blow-up'.

Cortázar's 'Blow-up' is one of his best known short stories and in spite

of the extraordinary amount of commentary dedicated to it, it still

remains one of his most problematic. 'Blow-Up and Other Stories' is a collection of short stories, written

by Argentinian author Julio Cortázar, who wrote 'Rayuela' (Hopscotch),

reviewed last week. The title story of the collection served as

inspiration for Michelangelo Antonioni's film title 'Blow-up'.

Cortázar's 'Blow-up' is one of his best known short stories and in spite

of the extraordinary amount of commentary dedicated to it, it still

remains one of his most problematic.

There are many things that are confusing. The hesitancy around the

person of the narrator, the grammatical permutations, the mixture of

first and third person narration, the double time of the narrative

(first the original scene at the parapet of the Quai de Bourbon and then

the repetition of the scene in the fifth floor apartment of the

writer/photographer Roberto-Michel).

|

Michelangelo Antonioni |

There is also the rotation of the subject positions taken up by the

boy, the blond woman, the man in the grey hat and Roberto-Michel

himself. Finally the 'dead' (and alive) status of the narrator at the

end of the story. It is true that many of these structural and narrative

effects or devices are to be found in many of Cortázar's other short

stories. Julio Cortázar's "Las Babas del Diablo" (the Devil's Drool) is

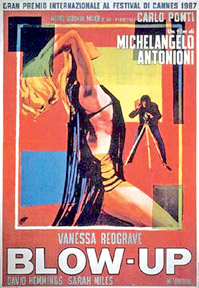

the acknowledged precursor of Michelangelo Antonioni's Blowup (1966),

rather than his short story 'Blow-up' (which inspired the style and the

title). This type of writing is typical of the Boom era, which I have

been exploring for several weeks.

In the Antonioni film, a photographer, Thomas (David Hemmings), blows

up a photograph and discovers a hidden gunman in the bushes. Thomas

initially believes his photograph saved an old man from being murdered

but discovers later that the murder happened anyway. In the Cortázar

short story, a photographer thinks he has captured the bittersweet

seduction of an adolescent by an older woman only to discover to his

horror that she is "pimping" him for a dirty old man waiting in a nearby

automobile.

Moving into the surreal, the photograph becomes a movie or rather a

photomontage of moving figures. In a further transformation, the

photographer is drawn into the slow motion of the photo montage. He

becomes his camera, becomes the seduced boy and yet remains himself. It

is while he is in this tripartite state that he is murdered by the old

man and lies dead in the photograph staring at the sky as camera, boy

and photographer are all rolled into one.

The film begins the day after Thomas spends the night at a doss house

where he has taken pictures for a book of art photos he hopes to

publish. He is late for a photo shoot at his studio with 60's supermodel

Veruschka, which in turn makes him late for another photo shoot with

many other models later in the morning. He grows bored and walks off the

shoot (also leaving the models and production staff in the lurch).

|

Blow-Up Movie Poster |

Image from Blow Up 1966 |

Exiting the studio, two girls, aspiring teenage models (Jane Birkin

and Gillian Hills), ask to speak with him butThomas drives off to look

at an antiques shop which he might buy. He then wanders into nearby

Maryon Park where he sees two lovers and takes photos of them. The woman

(Redgrave) stalks Thomas back to his studio, asking for the film. This

makes him want the film even more, so he misleads her into taking

another roll instead. He makes many blowups (enlargements) of the black

and white photos.

These blowups have very rough film grain but nonetheless seem to show

a body lying in the grass and a killer lurking in the trees with a gun.

Thomas is frightened by a knock on the door but it is only the two

girls again, with whom he has a romp in his studio and falls asleep.

Awakening, although they hope he will photograph them then and there, he

tells the girls to leave. Both film and story are meditations on

aesthetics and morality. Although the Spanish title ("Las Babas del

Diablo") is a colloquial phrase meaning to be in a dangerous situation.

However, Cortázar enjoys wordplay, and seems to be suggesting with the

title that the camera is a drooling devil - a lustful voyeur that is

capable only of lifeless illusion and is ultimately impotent. In the

story, Cortázar's narrator writes:

I think that I know how to look, if it's something I know, and also

that every looking oozes with mendacity, because it's that which expels

us furthest outside ourselves.

Later the photographe r/narrator expresses his rage:

It was horrible, their mocking me, deciding it before my impotent

eye, mocking me and I couldn't yell for him to run.

It would appear that Cortázar and Antonioni are saying that our media

is inherently alienating and dehumanizing. The camera has turned us into

passive voyeurs, programmable for predictable responses, ultimately

helpless and even inhumanly dead. These are dark thoughts indeed, but

the work of Cortázar and Antonioni are not exactly known for their

optimism.

As The Yardbirds perform in the nightclub, the eerily mute crowd is

so still that some of the people may not be people at all, but

department store mannequins or wax figures. If this is true, it fits

well with the mannequins in the window just outside the club and with

the plastic family enjoying their desert home in Antonioni's 'Zabriskie

Point' (1970). Either way, with the odd stillness of the crowd,

Antonioni is trying to get at the heart of the Cortázar story.

Rather than liberating us, our technologically driven art forms

(cinema, photography, and rock and roll) are finally numbing and

paralysing us because they seem to require passivity of their audiences.

At the very least, passivity is encouraged. In an Antonioni film, Jeff

Beck destroying his amp and guitar is not merely a realistic cultural

detail, it is symbolic of the artist's rage against his tools, which are

isolating, denaturing and incapable of conveying a clear vision, of

changing or influencing the quotidian. Caught up with the

media-controlled crowd, Thomas joins the scrambles for the guitar-neck

totem but discards it as meaningless once he is alone. He works

frantically to blow up photos and discover hidden truths. Once

discovered he lets them drift away.

Thomas goes to a party to raise interest in his murder case but fails

in an ending that is even darker than Cortázar's story. In the story,

the narrator may be dead, but at least his art was able to discover the

truth and the photographer was able to empathize and identify with the

victim to the point of dying in his place, surely a positive outcome for

a work of art. In Antonioni's film, nothing is done, nothing is learned

and nobody cares. "A murder? So what!" his characters seem to say. In a

dialogue of total emptiness, Thomas talks to his stoned editor, Ron

(Peter Bowles):

Thomas: I want you to see the corpse. We've got to get a shot of it.

Ron: I'm not a photographer.

Thomas: I am.

Ron (muttering to himself as if Thomas has left the room, although he

hasn't): What's the matter with him? What did you see in that park?

Thomas (sighing): Nothing.

Seeing justice done is never a goal. It becomes clear that Thomas'

goals have always been completely aesthetic. When Thomas returns to the

park for the shot he wants to finish out his book, he discovers the body

gone. He smiles wryly. Art for him is an illusion, nothing more than a

game of make-believe where we can dream away our lives in childish play.

The real world is even less than that - it's not even amusing. At the

end of Cortázar's story, we discover that the narrator is dead,

immobilized, metamorphosed into the very lens of the camera as it views

the world as a photograph. It appears that Antonioni reaches the same

conclusion with his justly famous ending.

When Thomas stoops to retrieve and toss an imaginary tennis ball back

into the mime game, he enters the frame of art, leaves reality and

ceases to be himself in pursuit of pure ćsthetics. The camera pulls back

to show Thomas walking utterly alone across a vast green field. Using a

dissolve, Antonioni causes him to suddenly disappear like the ghost he

has become.

The two American versions of the story are a copy of a copy which all

but obliterate the original Cortázar story. They switch from photography

to sound, but the inability of technology to intelligently capture

nature and the ontological merging of artist and medium are still the

prevailing themes. In Francis Ford Coppola's The Conversation (1974),

Harry Caul (Gene Hackman), becomes convinced that his surveillance tape

will result in the deaths of the young couple he has recorded as they

walk through San Francisco. The festival atmosphere, is clearly a subtle

nod to Antonioni but the disturbing ending suggests the influence of

Cortázar. Harry discovers that he has been completely wrong and has

inadvertently helped the couple commit murder. Finally, they turn his

technology on him as he is drawn into his own "aural photograph", and is

left as paralysed and impotent as Michael in the Cortázar tale.

In Brian De Palma's 'Blow Out' (1981), Jack (John Travolta) captures

a sound that equals the murder of a presidential hopeful. Unlike

Antonioni's amoral protagonist, Jack is driven by a desire to do what is

right, much like Harry in 'The Conversation' and Michael in 'Las Babas

del Diablo'. However, also like them, he solves nothing and saves no

one; he only discovers his own impotence.

Plus his defeat results in his own moral corruption, a conclusion

suggested more by Cortázar than Antonioni. Jack works as a soundman for

cheap horror movies and "Blow Out" opens with him criticising a "bad

scream" used in a shower knifing sequence. When Manny (Dennis Franz)

murders Jack's love interest, Sally (Nancy Allen), Jack is close enough

to record her scream but not to save her life. In the closing scene of

the film, we see the ruined hero listening to her scream which has been

as the needed scream for the horror flick - a snippet of aural snuff.

Jack has merged with his technology and has blurred reality and fiction

so that the real no longer matters and the fiction is not even good art.

All four tales make the same point - art is impotent to do anything but

corrupt the artist. |