|

After thoughts on the keynote address:

Taking Sri Lankan literary creativity into the folds of world

literature

By Dilshan BOANGE

The twelfth Godage National Awards held on September 2 at the

Mahaweli Centre paid tribute to several esteemed personalities whose

contributions to literary developments in Sri Lanka are truly

monumental. The keynote speech at this august occasion was delivered by

journalist Malinda Seneviratne who spoke on a topic and theme that

resonated with a lot of timely significance to Sri Lanka's community of

writers. Malinda touched on the matter of language and literature and

the argument of 'ownership' of literature.

|

|

Arundathi Roy |

|

|

Charles Dickens |

Who owns what when a work goes beyond its original language and

transpires as a 'translation' along the channels of 'world literature'?

Poetry was the genre that was made the platform for the theorem to be

exemplified as seen fitting by Malinda who put to the audience of who

owned those lines of verse he read out in Sinhala. Was it the poet Nizam

Hikmet who wrote them in Turkish or the one who translated them to

English, or was it Malinda who translated them in being read out in

Sinhala, or was it us the audience who listened to it all? I see the

argument brought forward by Malinda taking on a very significant facet

related to Print Capitalism.

Print capitalism and literature

It was as an undergraduate at Colombo varsity reading for a special

degree in English that I came to know of print capitalism and its

theoretical foundations, which primarily deals with Benedict Anderson's

views that the invention of the printing machine and consequent

circulation of literature that contributed much to the growth of the

concept of the nation-state. Print capitalism is on the one hand about

commoditization of the written word, and consequently leads to (one may

say) the establishment of languages of power or prestige in the global

scenario of consuming literature as another commodity. Yes about owning

a work of literature as a consumable commodity (in terms of an audience)

comes very visible when you consider how many books are bought from

bookshops around the world on any given day.

In that sense the consumer can claim ownership over the product

purchased by him through the channels that from the publishing industry

of the present age. After all I am not willing to say that the Tintin

books in my bookshelf belong to Georges Rémi aka Hergé! But then the

question of who can claim the greatness of having created the 'work' and

not merely the 'product' comes up along with issues of copyrights now in

this modern age of commoditized literature. Copyrights and rights

related to the work's transformation into a commodity is of crucial

importance to present day writers mainly if the writer wishes to be a

fully fledged 'Author' whose occupation is writing/creating literary

works.

Markets and earnings

In this light translations and who owns them and who makes money from

their sales is not an aspect of the publishing industry that can be

negated. Although today's sales of copies of the Iliad or Odyssey do not

contribute to Homer's estate, the matter of royalties takes a very

significant facet once a book enters the streams of print capitalism.

This connects with what I once told a friend of mine who asked me how

can a writer in Sinhala make a living since sales would be very limited

on account of the potential reader base (market scope) being essentially

within Sri Lanka, and that too would be a relatively small number. Yes,

unless it conforms to the teen romance novel category in popular Sinhala

fiction it is unlikely that mega sales could be expected.

Even a highly creative work of fantasy fiction that may be something

along the lines of a Harry Potter or a Disc World novel with potential

of becoming a global hit may not reach its probable heights if it does

not try to reach audiences beyond our national borders. Therefore

translations become a very crucial factor in helping writers of Sinhala

and even Tamil (although one may assume that India does have a possible

market for Tamil literature written by Sri Lankans) to reach new

audiences and also reap the benefits of print capitalism of the present

age.

Lack of institutional impetus

The competitiveness of course may require writers to become more

audience oriented and thereby market focused, which is of course not the

most faltering prospect for a writer who considers his creations to be

for the primary purpose of literature as art. But nevertheless Sri

Lanka's literary ethos may very well find a significant niche in the

stratosphere of contemporary world literature if English translations

(and translations in other languages which are widely used) were

produced more widely. On this line of thinking Malinda brought out an

important point recalling what Liyanage Amarakeerthi (Sinhala scholar

attached presently to Peradeniya University) who presumably was a

contemporary of Malinda's at campus had said.

|

|

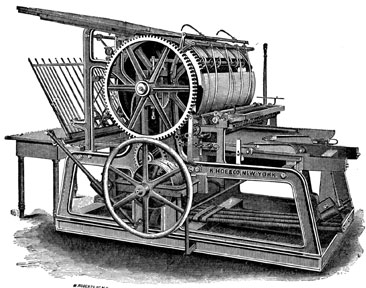

Printing press |

Amarakeerthi had said that although every year the English department

produces a set of English Hons. graduates not many of them would care to

associate with the Sinhala Hons students and offer to do English

translations of their works of creative writing which no doubt would be

helpful to the latter's career development. This argument seems to take

on a criticism that has do with a social dimension that may not

necessarily produce a possibl solution to the lacuna of effective and

wider English translations of Sinhala literary works. In my opinion the

criticism needs to be directed at the institutional track more than the

social aspect.

To the best of my knowledge the present university system in Sri

Lanka does not offer any courses in creative writing. Translation

methods and techniques aren't part of the curricula of the English

departments of the present university circuit.

This in my opinion is a severe lacking in the system. English and

French are the two most wide spread European languages, with a

considerable number of works in those languages being translated into

Sinhala every year, but how many Sinhala novels are translated into

these two languages to reach readers outside our shores? This in my

opinion is a sad state of affairs for which the system needs to be

critiqued.

I came to know through Jayashika Padmasiri a journalist and now a

published poetess, that at the University of Leeds, where she is reading

for her BA in English, it is mandatory for a student of English to take

a course in creative writing each year as part of the course selections.

Therefore, here in Sri Lanka more of an institutional thrust could be

created within the curricula of universities to serve as impetus for

students of language and literature to take up endeavours of literary

creativity.

Sri Lanka's literary voice in the global sphere

I fully agree with what Malinda said in his keynote speech that a

work of literature does not devalue in its integrity simply because it

didn't get translated in to the number one international language. But I

also wish to cite novelist Milan Kundera says of Franz Kafka (one of the

most celebrated and revered figures in modern European literature) in

his work The Curtain: an essay in seven parts, which is that had Kafka,

being a citizen of the Czech Republic, written in the Czech language and

not German (which had been his first language) the 'world' would not

come to know of a Franz Kafka.

I believe there is much truth in this Kunderian perspective which is

sage advice for Sri Lanka's contemporary writers. The Sri Lankan ethos

in its manifold forms of creative expression could in this day and age

of modern technological conveniences make significant achievements if it

were to more effectively enter the folds of print capitalism.

|