|

Professor Yasmine Gooneratne:

Not promoting the pretensions of' ‘literary theory'

By Ranga Chandrarathne

After receiving a first class Honours degree from the University of

Ceylon, Gooneratne attended Cambridge University in the late 1950s. For

her doctoral thesis she selected Sri Lankan Writing in English. After receiving a first class Honours degree from the University of

Ceylon, Gooneratne attended Cambridge University in the late 1950s. For

her doctoral thesis she selected Sri Lankan Writing in English.

It was, as far as I am aware, the second Ph.D. awarded by Cambridge

University on a topic outside its Euro-centric orbit, the first having

been E.F.C. Ludowyk's thesis on English education in Ceylon.

On her return to Sri Lanka, Dr. Gooneratne continued her teaching

career at the University of Ceylon, Peradeniya where she first focused

on British literature by examining satire and irony, key elements which

later turned out to be important features in her own critical and

creative writing, particularly in "A Change of Skies".

After teaching for ten years at the University of Ceylon, she moved

to Australia with her physician husband in 1972 and she spent 30 years

before returning to Sri Lanka. She is the author of over 20 books in a

variety of genres that include four volumes of poems, three novels and

one immensely readable personal memoir of her family.

In 1999, Prof. Gooneratne collaborated with her husband, the

historian and environmentalist Dr Brendon Gooneratne, in researching and

writing an intriguing biography of an enigmatic Englishman, Sir John

D'Oyly (1774-1824).

Her second novel, "The Pleasures of Conquest" was published in 1995

and was short listed for the 1996 Commonwealth Writers Prize.

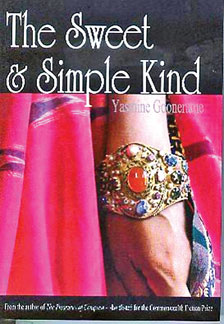

Gooneratne's latest novel is "The Sweet and Simple Kind", first

published in 2006 in Sri Lanka.

This 645 page long social chronicle is about two intelligent young

women from a distinguished and highly political family who pursue their

personal freedom in postcolonial Sri Lanka.

Gooneratne has also published a number of critical works on

individual authors such as Jane Austen, Alexander Pope and Ruth Prawer

Jhabvala, studies of the literature and culture of Sri Lanka, and essays

on other Commonwealth and Postcolonial writing. Her publications are a

testament to her wide range of interests and skills.

Professor Gooneratne had received several prestigious prizes and

honours here and abroad: the Sahithyaratna award for literary excellence

in Sri Lanka, the Order of Australia for her work in literature and

education, the Raja Rao award from India's Samvad Foundation, the

Marjorie Barnard Prize for literary fiction in Australia. Besides her

novels have been shortlisted for both the Commonwealth Writers' Prize

and the Dublin Impac International Award.

The following is an exclusive interview given by Professor Gooneratne

to the Montage:

Q. After you obtained a first class honours degree from the

University of Ceylon, you studied at Cambridge University. For your

doctoral thesis you wrote on Sri Lankan Writing in English. Your study

of 19th century Sri Lankan literature, English Literature in Ceylon 1815

– 1878 is considered a landmark study.

A. Is that right? I can't tell you how happy I am to hear

this. I remember choosing the topic because I had a sense that many

writers working, as I was, in the English language in Sri Lanka, had

little or no perception of any kind of home-grown tradition.

By this I mean that though we might have read Samuel Purchas's

description of our country as an exotic 'Paradise of plenty and peace',

or Keats's famous reference to the pearl-divers of Mannar in his poem

'Isabella and the Pot of Basil', we had no knowledge of poetry or

fiction written by people who had actually lived here and...

attempted to describe local landscape or local characters. I hoped

that research into what had been written and published here in the 19th

century might provide us with some background, some basis on which to

build future writing.

Q. Your dissertation is said to be the second Ph.D. awarded by

Cambridge University on a topic outside its Euro-centric orbit.

A. That's probably correct. I believe the first might have

been Professor E,F.C. Ludowyk's, which was on the subject of English

education in Ceylon.

Q. What made you to look at Sri Lankan writing instead of

working on popular English authors or theories?

A: My first choice among 'popular English authors' would have

been Charles Dickens, Jane Austen, or Alexander Pope. All three were

family favourites throughout my childhood, and I would have been on

familiar ground in taking up any one of them. But my father introduced

me to our eminent ancestor, his grandfather the 19th century Sinhalese

scholar and poet James de Alwis.

I read de Alwis's introduction to the Sidat Sangarava, and realised

that part of the 'tradition' I was seeking might lie in his work. A

detailed study of de Alwis's literary criticism is an important part of

my thesis. I read de Alwis's introduction to the Sidat Sangarava, and realised

that part of the 'tradition' I was seeking might lie in his work. A

detailed study of de Alwis's literary criticism is an important part of

my thesis.

Q. In addition to your outstanding academic work on subjects

such as the work of Jane Austen, Alexander Pope and Ruth Prawer

Jhabvala, your studies of the literature and culture of Sri Lanka, and

your essays on other Commonwealth and Postcolonial texts, you have

produced significant work of a creative kind, mainly fiction and poetry.

What factors influenced you in your creative writing?

A. I came late to creative writing, you know. Of course, like

most college students and undergraduates, I tried my hand at writing

short stories, and even poetry, at Bishop's College, and later at

Peradeniya.

My teacher at Bishop's, Mrs Pauline Hensman, encouraged this,

although she never professed herself to be a teacher of 'creative

writing'. But I was never happy with the results, either at school or at

university, they seemed to me to be basically imitations of the writers

I most admired, with nothing original about them. A clearer

understanding of what it really meant to write poetry came with the

death of my father in 1959.

Three days after his funeral, I wrote "Review" in his memory, and I

recognised this poem as definitely, uniquely, my own. Following that,

flood-gates seemed to open, and poetry poured through them.

The poet Lakdasa Wikkramasinha was alive at that time, he read some

of my poems, and urged me to publish them. With my husband's

encouragement and help I did so, printing the poems on a Heidelberg

press at T.B. Godamunne's printing establishment in Kandy.

Word Bird Motif appeared in a limited edition of 53 poems, with a

beautiful cover by Stanley Kirinde, who was working at Peradeniya as an

Assistant Registrar at the time. I sent a copy of the book to Patrick

Fernando, hoping he would review it.

I didn't know him personally, but I had read some of his poetry, and

admired it more than that of any one else writing at that time. Patrick

surprised me with a stunning review in the Daily News, which was then

under Mervyn de Silva's editorship. Fiction-writing came later.

Q. When? And how?

A. I was in Australia by then, having published a book on Jane

Austen for Cambridge University Press in 1970, and resigned from

Peradeniya in 1972. I had joined Macquarie University as the English

Department's 18th century 'expert' - a term that was popular in

Australia at the time, but one which has always amused me, for how can

anyone teaching authors such as Dryden, Pope, Johnson, Byron and Jane

Austen profess to be an 'expert' on their work!

They all, and especially Pope, "snatch a grace beyond the reach of

art". And then again, the problem with working on an author like Jane

Austen, a consummate stylist, is that nothing from one's own pen (or

computer!) can ever compare. So nothing could have been further from my

mind than actually writing fiction of my own.

Until Macquarie University chose to give me its first higher doctoral

degree - that of Doctor of Letters (D.Litt.). That was a landmark event,

for the University, and for me.

It inspired me to write a book about my family, mainly for my

children, who were growing up in Australia, and had no knowledge about

the literary achievements of their ancestors and kinsfolk: people such

as their great-grandfather James de Alwis, or (another

great-grandfather) Canon S.W. Dias Bandaranaike, who translated The Book

of Common Prayer into Sinhala, or Sir Paul Pieris, the historian, a

great-uncle. Writing about the personalities of my relations (many of

whom were fairly volatile, to put it mildly!) I acquired some experience

in drawing character.

That was how Relative Merits came to be written. It was published in

Britain in 1986. A huge success! Still in print, still going strong!

Q: In addition to your wide range of academic writings, you

have covered fiction, memoirs, and poetry. If you have to select one

genre, what would be your choice?

A. Oh, fiction, every time. In my experience, poetry has come

out of gut-wrenching sadness, the misery caused by death, loss, and

exile. I don't want to deal with sadness at my time of life.

Q: You combined satire and social history in an account of the

westernised lifestyle when you wrote about your ancestors in Relative

Merits: A Personal Memoir of the Bandaranaike Family of Sri Lanka in

1986. In my view, you use satire as a powerful tool in your fiction. A

good example of this, perhaps, is your first novel, A Change of Skies.

Would you please comment?

A: Yes, there's no doubt about the fact that satire is a

powerful tool in fiction. But it requires an educated and sophisticated

audience to be effective. I was fortunate to find such an audience in

Australia, when I published A Change of Skies. Without such an audience,

readers who can see the subtle difference between satire and personal

attack, it can become a dangerous weapon for an author, however

well-intentioned, to use.

Q: Many people who are now into postcolonial literature may

have forgotten that you are a pioneer in this field. You were a

path-finder in promoting post-colonial writing with your former

colleagues such as Gareth Griffiths through your work at Macquarie

University where you had a Personal Chair. Would you please give us a

summary of your work in this field?

A: The 1970s were exciting years, when very classy writing was

emerging from the West Indies, from India, and from Australia. V.S.

Naipaul, Samuel Selvon, George Lamming, Patrick White were all at the

peak of their form. Meenakshi Mukherjee in India made her mark as a

brilliant, perceptive critic.

No one who was teaching English at the time could have failed to

recognise the excellence of the material available. I was one of the

many who did, and introduced it to my students. I'm very pleased to

recall that I placed a novel by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala on my text-list at

Macquarie, years before her book Heat and Dust made her an

internationally well-known author.

Q: In your opinion, how far has this new discipline of

post-colonial writing progressed? What are its obvious shortcomings?

A: This may surprise you, coming from a former Director of a

Centre for Postcolonial Studies, but I've never been able to take

'post-colonialism' (with or without the hyphen!) seriously. Remember

that once, very long ago, it was known as 'Commonwealth Literature'.

Then the academics tired of that and re-christened it 'The New

Literatures in English'. But that didn't suit everyone, and another

switch brought the title 'Postcolonial'.

Doubtless yet another title will be upon us some day soon! Matters

have been further complicated by the sudden desire among academics to

pay homage at the altar of literary theory emanating from Europe.

As a result, the unfortunates who write PhD dissertations these days

have to make due obeisance to Derrida et al before they can move on to

real literary criticism: by which I mean the study of good writing by

good authors. I'm glad I'm not involved in promoting the pretensions of

'literary theory', and I'm happy to say I never was.

Q. According to Sunil Govinnage, you are the pathfinder of

writing about the Sri Lankan diaspora in Australia. In one of his

academic papers on your award-winning first novel A Change of Skies, he

writes: “When Yasmine Gooneratne published A Change of Skies in 1991,

she also established a tradition of representing the Sri Lankan diaspora

in the Australian literary scene. This is an important issue that many

of the critics who have evaluated Gooneratne's work have tended to

overlook".

What are your comments?

A: Yes, I've read that paper of Dr Govinnage's, and I do

appreciate his evaluation of my contribution to Australian literature

and culture, not to mention his extremely kind comparison of my writing

to that of the great Maxim Gorky! I'm not sure, however, that I can be

said to have established a 'tradition'.

|

|

Prof. Yasmine Gooneratne with Dr.

Lakshmi de Silva |

It's just that a number of Sri Lankans arrived in Australia a little

later than I did, and they too wrote fiction or poetry or drama about

the experience of exile and immigration. I was probably the first to do

so successfully.

Q: In your edited collection of short fiction, Stories from

Sri Lanka (Heinemann, 1979) you write: “In modern times, the writers of

Sri Lanka have been influenced by European fiction, and have absorbed

many attitudes (both to life and to literature), that originate in the

west.” Looking at current English writings in Sri Lanka, do you think

the situation has changed today?

A: I think so, largely due to the lively, energetic writing of

writers such as Carl Muller, the sound literary criticism of reviewers

such as Dr Lakshmi de Silva, and the emergence of a publisher such as

Perera Hussein. But there's no reason why our writers, in observing the

world around them, should be called on to reject the work of overseas

authors.

The increasing attendance over five years at the Galle Literary

Festival indicates, in fact, that they do not. And this is as it should

be.

Isn't it far better that our writers should open their eyes and their

hearts to literature from beyond our shores than that they should be

confined, due to irresponsible educational policies and incompetent

teaching, to the pathetic situation of 'frogs in the well'?

Q: How do you define “Sri Lankan English writings” and should

such work be confined to our island alone?

A: I take it that in applying the phrase "Sri Lankan" to

English-language writing, you're doing so in the context of

categorisation and qualification: Who, for example, should be considered

"Sri Lankan" when literary prizes are offered, or national honours

bestowed? Should a Sri Lanka-born individual whose application for a

literary award comes from an address in Washington or Sydney or Mombasa

be considered "Sri Lankan" enough to qualify? I'm afraid I don't know.

And, to be perfectly frank, I don't want to know. Such considerations

are irrelevant to good writing. The most valuable prize, the most

satisfying honour, an author can receive is the rapt attention of

well-educated readers, and that, as I know from both experience and

observation, comes independently of any prize or so-called honour.

The news I received last week that Little Brown, the company that

published my last novel The Sweet and Simple Kind in the UK, has been

called upon to reprint 4,000 extra copies in paperback for the North

American market has given me tremendous pleasure and encouragement. It

means that people out there, people I've never seen, are reading my book

and loving it. That pleases me more than honours and awards.

Q: And yet you have yourself received several prestigious

prizes and honours here and abroad: the Sahithyaratna award for literary

excellence in Sri Lanka, the Order of Australia for your work in

literature and education, the Raja Rao award from India's Samvad

Foundation, the Marjorie Barnard Prize for literary fiction in

Australia, to mention only four.

Besides which your novels have been shortlisted for both the

Commonwealth Writers' Prize and the Dublin Impac International Award.

These are rare achievements. Do you have anything against the giving of

prizes to deserving authors?

A: No, not at all. All the instances you have just mentioned

pleased me very much when I was informed that I was to receive them, but

they were awards and prizes for which I did not personally apply, nor

did I have to compete for them. If a committee or a publisher wishes to

nominate an outstanding book or a deserving author for a literary award,

good luck to them, I say! But a writer's mission - my mission - is to

put words together as best as I can, in fact to write. Not to compete

for prizes.

Q. What advice would you give to Sri Lankan academics of the

new generation who are pursuing academic careers in literature?

A: Don't let anyone at your university talk you into teaching

'creative writing'! Presenting academic courses and awarding academic

degrees in 'Creative Writing' has become fashionable overseas, and it's

a popular policy with administrators because it's a money-spinner for

the institution. Students think it's a soft option, and enrol in large

numbers. Creative writing simply cannot be taught.

What you can do, what you must do as a responsible teacher, is to

teach your students to read and understand literary texts. Encourage

them to re-read the classics, in English as well as in other languages.

And stay away from theory.

Q: What are your current literary projects?

A: I have an on-going occupation as a literary editor. This, like a

series of 8 essays on "The Practice of Writing" that I wrote recently

for MONTAGE, is part of a small, personal campaign to improve the

standard of English writing in Sri Lanka, but it also gives me a lot of

pleasure, because I take pride in the books that I see into print.

I have a novel in draft, which I have put aside until I think the

time is right for publishing it. I'm reading a lot - all the books I've

always meant to read, and never had the time.

And I'm learning a lot about the charm of language from conversations

with my 3-year-old grand-daughter - they're 'literary' because she likes

telling stories, and finds me a good listener.

|