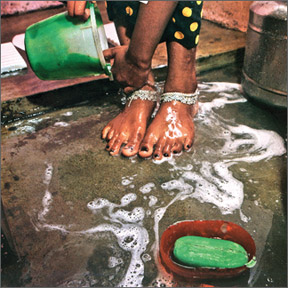

Health challenges of basic sanitation and hygiene

By Shanika SRIYANANDA

This story is not a rosy one. It's about the one billion South Asians

clamouring for toilets. Though sanitation is not an attractive topic, it

means a lot to these people as it has a bearing on their 'dignity' and

'cleanliness'.Out of this number, about 700 million men, women and

children do not have toilets and have to adopt a undignified modes to

relieve themselves in remote rural villages and the poor in informal

urban localities in metropolitan cities. This story is not a rosy one. It's about the one billion South Asians

clamouring for toilets. Though sanitation is not an attractive topic, it

means a lot to these people as it has a bearing on their 'dignity' and

'cleanliness'.Out of this number, about 700 million men, women and

children do not have toilets and have to adopt a undignified modes to

relieve themselves in remote rural villages and the poor in informal

urban localities in metropolitan cities.

They are exposed to severe health risks, violence and add to

environmental pollution.

A majority of schools do not have decent toilets and hand washing

facilities for children hence, a chance to change their hygiene in the

next generation is missed out.Economically better performing regions

during the global economic slowdown is facing health challenges of basic

sanitation and hygiene.

This is a problem which the developed world faced and resolved in the

early 18th century as a fundamental human development. This neglect in

the way of human development may be consequential for future economic

development potential.

The economic, social and environmental consequences of this situation

are globally known. The World Bank estimates that the consequences of

inadequate sanitation cost India approximately USD 53.8 billion - 6.4

percent of GDP - every year and Bangladesh BDT 295.5 billion (US$4.2

billion)-6.3 percent of GDP.In India alone every day, more than 1,000

children under the age of five die from diarrhoea caused by dirty water,

lack of toilets and poor hygiene, placing India in the top spot in world

diarrhoea rankings.

Pakistan and Bangladesh, two other South Asian nations, follow close

behind.They aspire for dignity, privacy and freedom from a life of shame

and embarrassment.

They want functional toilets, waste water disposal systems, and

adequate and regular arrangements for disposal of solid waste.All

countries in South Asia are signatories to the right to water and

sanitation; however, almost half the region's population is without

improved sanitation andmore than seven hundred million people defecate

in the open every day.

The report - South Asian people's perspective on sanitation -

released ahead of the SAARC Summit held in The Maldives have highlighted

people's view through interviews conducted in South Asian countries,

focus group discussions held with underprivileged communities and social

groups across Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.All

countries in South Asia are signatories to the right to water and

sanitation; however, almost half the region's population is without

improved sanitation andmore than seven hundred million people defecate

in the open every day.

The report, which prepared together with the Freshwater Action

Network South Asia (FANSA) and the Water Supply and Sanitation

Collaborative Council (WSSCC) quoted people who believe that sanitation

programs and projects have failed because of a lack of involvement and

commitment from both communities and external agencies and the

consequent lapses in technology, planning, implementation, supervision,

support and, above all, accountability.

For making services sustainable and programmes successful, the

quality of construction work should be improved, minimising vested

interest group to benefit, controlling corruption and establishing an

effective operation and maintenance system."Why is this pathetic

condition socially and politically accepted in the region, which

otherwise inspires the world in many areas? Put another way, how this

very basic developmental challenge has been addressed by developed

countries? The factors we found are public sector investment and greater

political commitment at higher level which transformed the societies.

There is political commitment to change but not at the required

levels, with new policies and investment for public services but these

are not adequate. The region also faces the inherent problem of

exclusion.

The biggest, and often overlooked, problems of exclusion and

inequality deny millions of poor and marginalised people of their basic

rights", Mustafa Talpur, Regional Advocacy Manager-WaterAid South Asia

said at a function held in Colombo to release the report in Colombo.

He said sanitation had never been on the agenda of SAARC in 16

summits over the span of 25 years and the Millennium Development Goal

target for sanitation to be achieved by 2015 rests with countries in

South Asia and it had demonstrated that it can make things happen with

political will."If South Asia makes progress on sanitation, then the

world will make progress.

The overarching message emerged from peoples' voices across the

region is that their political leadership must take a collective resolve

in the region to promote right to sanitation and dignified lives, work

to provide them and their children a disease-free and healthy

environment.

How this aspiration could be translated into a reality when this

region faces political hostilities, struggling to share a common

regional development vision. Can the issue of sanitation be a common

factor in this unfriendly political environment?", he said.Mustafa said

it was high time for SAARC political leadership to come up with clear

and ambitious targets, timeline and cash for sanitation and the SAARC

leadership needs to recognise that sanitation is the building block of a

dignified society in South Asia.

" They must recognize sanitation crisis in the region as diarrhoea is

the biggest child killer in the region.

There is a greater challenge of inequity in resource distribution and

service provision. SAARC can encourage such moves by national

governments.

They need to work out a regional mechanism for implementation,

coordination, research and knowledge sharing and steering the plan

through the existing SAARC secretariat and strengthening South Asian

Conference on Sanitation process", he pointed out.FANSA's Ramisetty

Muraili said the report clearly indicates that people want to live a

life of dignity and health, but are frustrated by lack of effective

support and failure of poorly planned and implemented projects, whereas

some communities are reluctant to adopt safe hygiene practices because

of sociological and cultural barriers and extreme poverty."Moreover, the

collective voice of the people also associates sanitation with notions

of happiness, pride, safety, health and education.

The study appeals to policy-makers to revamp institutional mechanisms

that invite community participation in sanitation projects.Above all,

the study calls for greater accountability and transparency measures and

a focus on human-centred development, targeting the below-poverty

communities in India and the hardcore-poor of Bangladesh and Nepal.

WSSCC's Archana Patkar said, "SAARC needs to recognise the sanitation

crisis in the region and challenge the inequity in the provision and

distribution of resources. Governments need to engage pro-actively in

matters related to water, sanitation and hygiene." She added, "The

regional mechanisms for implementation, coordination, research and

knowledge-sharing through the existing SAARC Secretariat is needed to

strengthen the process of the South Asian Conference on Sanitation", she

said.

The report states that the level of understanding of sanitation and

hygiene, and its articulation, was influenced to an extent by both the

educational attainment of respondents and interventions in the area.

Interventions made communities more educated and aware, and in turn

people in these communities described sanitation as 'hygienic toilets',

'closed drainage' and 'rubbish-free settlements'. For such communities,

it also meant regular maintenance of the facilities and sustained

availability of services. Similarly, it was observed, especially in

India and Sri Lanka, that the higher the educational status of community

leaders and respondents, the better knowledge they possessed and the

better they could articulate their understanding of sanitation.

However, at the same time even the illiterate respondents had a basic

understanding of sanitation and hygiene. Mina Begum of Aadibasi

Sundarpara of Shyamnagar, Satkhira, Bangladesh, is illiterate and

belongs to a minority group.

To her, sanitation means a hygienic latrine, safe drinking water,

washing hands with soap, and disposing of children's faeces in the

latrine. "Sanitation is essential for life. It is an important part of

our religion too. Cleanliness helps a person get a better education and

higher position in society. Hand-washing with soap after defecation is

very important for maintaining hygiene. Food hygiene prevents disease

and keeps children healthy." she said.There was also a difference

between women's perspective of sanitation and men's. For women it

especially meant keeping themselves, their houses and their

childrenclean.

Women from some rural communities in states like Tamil Nadu said that

a clean house gave them immense 'happiness' and 'pride'."Sanitation is

the basis for happiness and satisfaction. It urges me to get up early

and remains as the first thought for the day to keep my home and

surrounding clean. As the day starts with cleaning,the whole day then

becomes very active and happy" Punitha, Chinnaviai, urban panchayat in

the district of Kanyakumari in Tamil Nadu, India said.It is a matter of

dignity despite the gender.

Understanding of sanitation was closely related to open defecation

and the need for toilets, especially in crowded urban settlements.

Whether recalling exposure to a sanitation intervention or not, almost

all women and most male respondents reported feeling acutely embarrassed

in front of neighbours as well as outsiders in the absence of a private

toilet.

Privacy and dignity are especially important to women.

"There is a need for separate toilets for each house because people

without toilets are cornered by others and face difficulties

entertaining guests", that was the view of Gayani Mendis, from Galle,

Sri Lanka.The safety of men, women and children was often found to be

compromised by poor sanitation.

Open fields - especially in the night or during the rainy season -or

railway tracks were described as unsafe and instances of people losing

their limbs, or even their lives, and of women being molested were

frequently reported,"Everyone in the village goes to the nearby fields

for defecation.

According to 50-year-old Veerkala, 50, Kota Dewara, Uttar Pradesh,

India it was 'dirty, troublesome, time consuming and dangerous as well,

especially for women and physically challenged people. It is very common

for pigs to attack us from behind when we are squatting in the field.

We are forced to take someone along when going out to the

fields".Goma Chaudhari, community leader in Bhiratnagar Municipality,

Nepal said some people, especially children, still defecate in the open,

and while almost all households have toilets, the drainage is open and

sewage poorly managed. "People know about health and hygiene in general,

but they lack the attitude.

For example, they know the importance of hand-washing but do not act

upon it. I guess only 40 percent of people in the village are active

regarding their cleanliness."Many people across all the countries

believed that keeping one's body and environment clean, leading a

healthy life and protecting oneself from diseaseconstitute sanitation

and hygiene.

Those who had a clear understanding of hygiene perceived that living

in an unhygienic environment led to all kinds of diseases.

They said that following simple hygiene practices, like washing hands

before meals or cooking food, keeping the drinking water covered and so

on, would eliminate many of the diseases. They were clear that it would

therefore also contribute towards reducing poverty,H. A Chandana, from

the Uva province, Sri Lanka, who was quoted in the report, said: "It is

government responsibility that it should expand people's right to them.

I do not know much about non government organisations; if they help

people we deserve that.

I believe if people collectively struggle for the solution of

problems, they can achieve any goal. Considering the United Nations'

standards, it is the duty of the Sri Lankan Government to ensure access

to water and sanitation.""For Sughran Bibi, a housewife of Jungle

Barali, district Vehari, Punjab, Pakistan it her and her family dignity

to have a toilet. "In the absence of sanitation facilities, people feel

degraded,especially when guests arrive.

Many people have migrated from this place just because of poor

sanitation."Is sanitation is a 'right'? Although notions of sanitation

as a 'right' were not always clear in many countries, most people, whom

were interviewed, thought that it was important and it meant that the

government was responsible to provide adequate facilities and services

to the people.The disposal of used cloths and sanitary napkins is a huge

issue across South Asia.

In most countries they are thrown into nearby ditches or places where

other waste is thrown.

In Sri Lanka schools reported that as toilets lacked proper bins or

disposal systems, soiled napkins were strewn around toilets, dissuading

other children from using them.According to the report, projects have

been successful where there has been a high level of community

involvement from the planning to the implementation stage. Community

leaders in Nepal for instance suggested that projects need to first

sensitise communities to construct public and private toilets, and

engage local people to monitor and maintain the initiatives.

They believe that unless people take ownership of what they receive,

success is not possible. Most community leaders believe that support for

infrastructure alone is not sufficient to make sanitation initiatives

successful. |