|

The Gibson Cauldron:

Mobster Fantasies and Get the Gringo

By Dr. Binoy KAMPMARK

It was supposedly a trumpet blast signalling Mel Gibson’s return, but

Get the Gringo was released straight to view-on-demand in the US having

failed to make a decent theatrical run. (Indeed, it might even be said

it made no run at all.) The Los Angeles Times (Apr 19) quipped that,

‘Mel Gibson’s new movie Get the Gringo rolled into a handful of theatres

Wednesday night for what is certain to be the shortest theatrical run in

the actor’s history: one night.’ This is not entirely negative for

Gibson, even if commentary on this fact exudes it. VOD transactions

might well be the new nirvana, and he is hoping to capitalise on it.

That said, VOD tends to be the home of low budget experiments rather

than richly fed financed projects. Gibson himself suggested at an Austin

theatre where the film was being premiered that the ‘era’ was

‘different’. ‘Many people just like to see things in their homes. It’s

just another way to do it and a better way to do it. I think it’s the

future.’ That said, VOD tends to be the home of low budget experiments rather

than richly fed financed projects. Gibson himself suggested at an Austin

theatre where the film was being premiered that the ‘era’ was

‘different’. ‘Many people just like to see things in their homes. It’s

just another way to do it and a better way to do it. I think it’s the

future.’

Gibson has financed a film which features him as protagonist,

co-writer and producer, forking out an amount in the order of $20

million. That he should use his own deeply lined wallet will surprise

few. His drop in the film world has been spectacular – at least in terms

of film receipts and celluloid appeal. Edge of Darkness netted $43.3

million, a poor return on a hefty budget of $80 million.

Having been in a wilderness filled with anti-Semitic suggestions and

claims of domestic violence, Gibson’s Get the Gringo is not something to

lightly dismiss. It is fresh, raw, and sparkling.

Even Peter Bradshaw at the Guardian (May 10), a critic often hard to

please, had to admit that Gibson had ‘a disconcerting habit of releasing

good films just when his reputation as a human being is lower than low.’

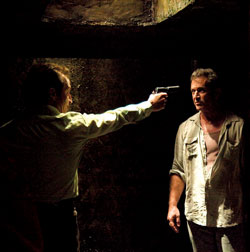

A criminal by the name of Driver is eager, opportunistic and perpetually

thieving. Millions of a mobster’s own returns go missing courtesy of

Driver’s eagerness, and he finds himself crossing the US-Mexican border

and ending up in the hands of the Mexican authorities. Naturally, the

dusky are corrupt, and make off with the proceeds. Driver, however,

isn’t too troubled. One thief’s loot is another’s purpose.

Absurdist, panoramic violence has its place (Gibson is always good on

searing flesh and blood stains), and a Mexican prison located near the

US border provides rich pickings. In this particular microcosm of

brutality that mimics the correctional facility of El Pueblito in

Tijuana, everything is available for purchase.

The sub-text to this is an obsession about a liver transplant for a

criminal overlord and the young boy (Kevin Hernandez) who can provide

it. Gibson rushes to the lad’s protection, becoming a rugged de facto

daddy. Perhaps the most striking scene is the assault on the compound by

the Mexican authorities, even as the attempted transplant is taking

place. The only tediousness, in the end, is that Gibson’s character

should win out. There is a virtue counter regarding criminality, and

Driver scented with saintliness. The sub-text to this is an obsession about a liver transplant for a

criminal overlord and the young boy (Kevin Hernandez) who can provide

it. Gibson rushes to the lad’s protection, becoming a rugged de facto

daddy. Perhaps the most striking scene is the assault on the compound by

the Mexican authorities, even as the attempted transplant is taking

place. The only tediousness, in the end, is that Gibson’s character

should win out. There is a virtue counter regarding criminality, and

Driver scented with saintliness.

Gibson is without doubt his own worst enemy, marshmallow soft as a

target, an oaf before the camera when he is not acting. He has a habit

of being guileless in company, oblivious to the recording media that the

twenty first century provides.

Screenwriter Joe Eszterhas obliged Gibson’s worst tendencies by

releasing an audio recording of the actor haranguing houseguests and

blasting his ex-girlfriend’s moral character. (The recording itself had

been taken by an alarmed but nonetheless ready Eszterhas junior.)

Eszterhas was himself wounded by Gibson’s apparent refusal to entertain

the scriptwriter’s The Maccabees on a notable 2nd-century BC Jewish

revolt that was as much directed against Hellenizing Jews as anybody

else.

The explanation for the rebuff, as simple as it is convenient:

anti-Semitism. Besides, The Maccabees project was only entertained, or

so we are told, to convert Jews to Christianity. Gibson remains, in the

views of such critics, a loather of Jews and a preacher of the Christian

creed. But whether he has reason to loathe the viewings and receipts on

his latest film effort will be a question to put to his accountant and

the judges who shunned him.

Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College,

Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email:

[email protected]

|