54-million-year-old skull reveals surprises about early evolution of

primate brains

by Bill Kanapaux

Researchers at the Florida Museum of Natural History and the

University of Winnipeg have developed the first detailed images of a

primitive primate brain, unexpectedly revealing that cousins of our

earliest ancestors relied on smell more than sight.

The analysis of a well-preserved skull from 54 million years ago

contradicts some common assumptions about brain structure and evolution

in the first primates. The study, also narrows the possibilities for

what caused primates to evolve larger brain sizes.

The skull belongs to a group of primitive primates known as

Plesiadapiforms, which evolved in the 10 million years between the

extinction of the dinosaurs and the first traceable ancestors of modern

primates.

|

|

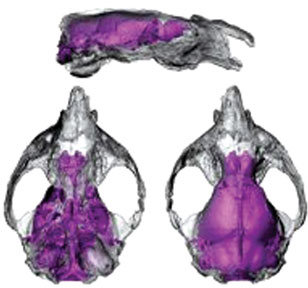

This image shows a translucent

rendering of the brain as it would fit inside the skull of

the 54-million-year-old primitive primate, Ignacius

graybullianus. |

The 1.5-inch-long skull was found fully intact, allowing researchers

to make the first virtual mold of a primitive primate brain.

"Most explanations on the evolution of primate brains are based on

data from living primates," said lead author Mary Silcox, an

anthropologist at the University of Winnipeg and research associate at

the Florida Museum. "There have been all these inferences about what the

brains of the earliest primates would look like, and it turns out that

most of those inferences are wrong."

Researchers used CT scans to take more than 1,200 cross-sectional

X-ray images of the skull, which were combined into a 3-D model of the

brain.

"A large and complex brain has long been regarded as one of the major

steps that sets primates apart from the rest of mammals," said Florida

Museum vertebrate paleontologist and study co-author Jonathan Bloch. "At

our very humble beginnings, we weren't so special. That happened over

tens of millions of years."

The animal, Ignacius graybullianus, represents a side branch on the

primate tree of life, Bloch said. "You can think of it as a cousin of

the main line lineage that would have given rise ultimately to us."

Nose first

In previous research, Bloch and Silcox established that

Plesiadapiforms were transitional species. Ignacius was similar to

modern primates in terms of its diet and tree-dwelling but did not leap

from tree to tree like modern fast-moving primates.

In many ways, the early primate behaved like living primates but with

a brain that was one-half to two-thirds the size of the smallest modern

primates. This means factors such as tree-dwelling and fruit-eating can

be eliminated as potential causes for primates evolving larger brain

sizes, Silcox said, because "the smaller-brained Ignacius was already

doing those things."

The mould suggests a "startling combination" of features in the early

primate that requires a re-thinking of primate brain evolution, said

Florida State University anthropologist Dean Falk, who was not involved

in the study.

"Hypotheses about early primate brain evolution often link keen smell

with nocturnal insect-eating, and a more recently evolved increase in

visual processing with fruit-eating in arboreal habitats," Falk said.

The move to larger brain size occurred during an evolutionary burst

that happened 10 million years after the extinction of the dinosaurs. At

that point, visual features in the brain became more prominent while the

olfactory bulbs became proportionately smaller.

More than likely, Bloch said, this change in brain structure and size

was related to primates living in closed canopy forests that brought

trees closer together and allowed for more leaping. But answering that

will require the discovery and analysis of new fossils.

Changes in brain size and structure in the early stages of primate

evolution have generated enormous debates for decades. But until now,

fossil evidence has been lacking. Many models of the ancestral primate

brain are based on tree shrews, which come from Southeast Asia and are

distantly related to humans. But with some 70 million years of evolution

between them and humans, "it turns out tree shrew brains are not a good

model," Silcox said.

The early primate's brain had relatively large olfactory bulbs,

indicating the animal relied on smell rather than sight. "Being visually

directed is one of the things that is a primate characteristic, but we

can tell from the brain that's not something that came in right at the

base of primates but evolved later," Silcox said.

Detailed picture

The fossil record provides the best test of inferences about brain

evolution, but until recently, fossil evidence for primates has been

mostly limited to teeth and fragmented jaws. But in past two decades,

limestone deposits in Wyoming have yielded well-preserved skeletons and

skulls.

The CT scan technique has become an accepted method for fossil

studies but most often involves medical scanners that are re-purposed

for fossils.

By contrast, the primate brain study used a more powerful

industrial-strength high-resolution scanner at Penn State University.

Claire Dalmyn, an undergraduate student at the University of Winnipeg

and paper co-author, traced more than 800 X-ray images of the braincase.

The effort took nearly a year and produced one of the best endocasts

they had ever seen for an extinct mammal.

"I couldn't believe what we were seeing," Bloch said.

Primate brains tend to be dominated by cerebrum, the most highly

evolved part of the brain, making it difficult to look at functional

areas and forcing researchers to focus solely on brain size.

"Brain size is interesting, but it's quite difficult to interpret

because in one brain, 50 percent could be made up of olfactory bulbs,

and in another brain, 50 percent could be made up of visual processing

areas," Silcox said.

In the primitive primate, the cerebrum had not yet evolved to the

point where it covered all of the other functional regions of the brain.

As a result, the relative sizes of different parts of the brain

provide a better picture of brain function and the early stages of

primate evolution.

The specimen came from north central Wyoming, near the entrance to

Yellowstone National Park. The intact skull is a rare find that allowed

the primate to be studied this way for the first time, Silcox said.

"This is very exciting in terms of the history of paleo-neurology,

the history of the study of brains in the fossil record," Silcox said.

Courtesy: Natural History

|