Modes of ‘Time’ manifested through trajectories of ‘Motion’

A review of the theatre production ‘Time and Motion’:

By Dilshan BOANGE

|

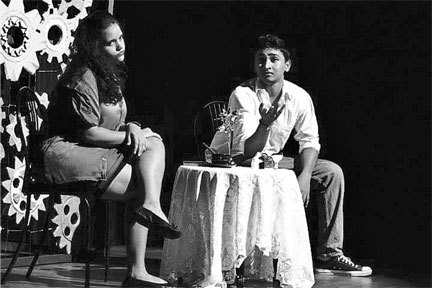

A scene from Time and motion

|

Sri Lankans, when we go to the theatre want to be entertained, we

want to laugh. It’s in our nature to want to see things optimistically,

and feel a sense of positivism. And even plays that have a very serious

theme and subject must bring out some comic relief here and there, and

create some laughs.

These were some sentiments once expressed to me by Gihan de Chickera,

a face known from both the screen and stage. The validity of such views

can be tested by studying the success of plays staged in Sri Lanka and

how many runs they enjoy in the theatre circuits enticing viewers to

watch them over and over again.

Time and Motion

In this context one hopes the theatre production Time and Motion

staged on August 4 at the Lionel Wendt directed by a debutante drama

directress Anushka Senanayake and produced by Swasha Fernando and

Trinushka Perera, will not be hesitant to test the waters of audience

receptiveness by going on the boards with repeated runs.

Presented by an ensemble of notably young talent, this production

truly does show much optimism in terms of Sri Lanka’s scope of producing

another generation of Thespians to succeed, in time, to the mantle

created and being created, by the big names in contemporary Sri Lankan

theatre. Time and Motion was a medley of five short plays performed (in

sequential order) as –‘Sure thing’, ‘Restless in the restroom’, ‘Philip

Glass buys a loaf of bread’, ‘Variations on the death of Trotsky’, and

‘Yes and No, also known as, It works.’

The production’s holism

The unique and distinctness of the character and technique

demonstrated of each play showed the production’s holism. Each

performance held its ground and drove on its own merits of subject,

topic and mode of dramatisation and was not dependent on one other, yet

contributed to building a larger expression of how one may perceive the

relevance of ‘Time’ and its non retractable ‘motion’ that defines human

existence. The performances were line up of short plays written by

contemporary American playwright David Ives as well as Anushka

Senanayake herself.

Sure thing

In Sure thing the seemingly uncomplicated instance of a boy trying to

get acquainted with a girl sitting in a cafe reading a book is revealed

for the many complexities that can occur dependent on the mood and

moment of the people involved. The characters in this short play show us

that ‘people are human’ and the outcomes of conversation can be

different, depending on the approach and interaction that ensues and

also how ‘Time’ may work, or not on one’s side.

The technique employed showed that if humans were allowed to redo and

rerun and rewind their ‘motions’ at will, the application of ‘Time’

would be ‘rewritten’. And thus mistakes in life would of course never

really be a human possibility as one could simply ‘erase and write over’

whenever ‘time is up’ at a given attempt to reach an objective.

The sounding of a timekeeper’s bell marked a new moment between Bill

and Betty who finally do pair up to go to the movies despite all the

complexities of humanness they carry as two people yet to know each

other but having had their share of complication created by members of

the opposite sex and the indignations they cause in their respective

lives.

The symbolic Bill and Betty

|

Anushka Senanayake |

Bill and Betty are thus symbols and also representative of a desire

that can never come true –the instant ability to do certain things in

life over, erase the mistakes, as if they had never happened. The stage

is thus a space where one can see what we would direly wish to rectify

in our lives, governed by the rigidities of time and its irreversible

forward motion, achieved through time ‘reconstructed’, and made our

redeemer from our own bungling.

Resolutions in washrooms

Restless in the restroom had a sense of being something of a classily

done comical ‘chick lit’ scenario theatricalised to express how time may

hold a different value to people based on their perception and

conception of time’s ‘motion’ even if made to share a common space.

The action picks off in the ladies’ washroom in the ‘Cardamom Grand’

Hotel as Brenda the Bride, her Maid of Honour, she has been a TV

commercial model famed for a one time appearance in a butter

advertisement, an erudite bespectacled pretty girl on her way to an

interview with a visiting Harvard professor to secure a grad

scholarship, get locked in together and unleash a spiral of female

melodrama as Brenda bawls hysterically in classic bimbo blondness how

her fiancé is insensitive and uncaring of her feelings based on his

indifference to, and lack of recognition of, two certain shades of pink,

apparently rather notably distinguishable to the female senses according

to the Bride, her MOH and the former model.

With the eventual arrival of a shy man who mistakenly wanders in to

this very same ladies’ restroom and again allows the door to get shut,

revealing to be the ‘Professor Mendez’ with whom the given appointment

had by then been missed by the intellectual young woman, a providential

turn of ‘motion’, it seems, occurs to salvage the scholarship hopeful to

whom ‘time’ had not been kind.

‘Pink’ sensibilities

Although the classically superficial fusspot bimbo bride may seem to

make no ‘sensible’ argument in alleging her intended husband as

insensitive and unsympathetic to priorities in her life, the

counterargument could be that the ‘pinks’ concerned are meant to be

symbolic and representational of how a woman such as herself relates to

objects that bespeak her interiority.

The failure to see distinctions in those ‘colours’ could mean that

‘Shehan’ the fiancé, through his failure to see distinctions of two

symbols with marginally distinguishable difference, fails to grasp and

perceive a facet of Brenda’s interiority.

The likes of Shehan are thus in their ‘manliness’ unable to connect

with the ‘emotional being’ within the likes of Brenda. Food for thought,

one may say, when gauging how the seemingly superficial may speak of

divides between genders seeking expressionisms.

Pausing ‘Time’ for ‘Motion’

|

A scene from Time and motion |

‘Time’ and ‘Motion’ as concepts and phenomena took an entirely new

theatrical dimensionality in ‘Philip Glass buys a loaf of bread’. The

act built on a host of symbolic ‘motional’ elements as dance and jerky

repetitive verbalisation to signal deviation from chronology and

communication as perceived in conventionalism.

The intricacies involved in this performance required bodily

precision and dexterity to be ‘spot on’ and the players pulled it off

with great skill and ability which surely was the result of dedicated

rehearsals to ensure the smooth flow that seemed nothing short of

natural to the four players who should be applauded for the execution of

an act that entreated the audience to show sentential deconstruction and

reconstruction coupled with dance synchronisations could redefine time

and motion and present an altered version of reality.

Enter comrade Trotsky

The fourth short play, which was after the intermission is one that

could be thought of as a brilliant rightwing script theatricalised with

elements of the comic, the darkly comic, tragic, and also doleful.

Variations on the death of Trotsky can be thought of as tastefully

rightwing not because it creates a comicality out of the assassination

of exiled Soviet revolutionary Lev Davidovich Bronstein better known to

the world as Leon Trotsky, but since the play ‘humanly’ relooks at the

assassination which happened in Mexico of one of the most prolific

political figures of the 20th century who in the belief of upholding the

ideals of the Bolshevik revolution became Stalin’s most formidable

opponent in international communism.

The performance gives room to explore a possible alternative from a

hypothetical Trotsky built on the premise of humanism.

The humanisation of a Soviet leader as Trotsky as one who must be

sympathised with for fearing death and yearning for humanistic

understanding of why he was killed so brutally, makes the play’s

discussion one of critiquing leftist dogma. After all, orthodox Soviet

socialism rejects humanism as a specious machination of the capitalist

system to deprive the proletariat to become empowered.

Acts segmented by lighting

The variations were acts segmented by the control of lighting with

blackouts ending each ‘variation’, which at times left the audience in a

quandary as to whether the short play had ended towards the latter acts.

Yet the hilarity delivered by some of the acts at the inception came

to a definite halt when a doleful Trotsky after fully grasping the fact

that he is destined to die as written in history, says he would like to

take the time available to him to smell the flowers in his garden, a

simple act that makes him every bit human.

A masala mix of comedy

The finale showed ‘Time’ as a precious resource running out for young

Rahul Malhotra who must get married to escape a family curse that ends

the lives of the males who do not wed before turning twenty-one.

A hilariously rib-tickling short play Yes and No, also known as It

Works is an Indian scenario where masala bungling and Bollywood apery

are tenets that drive the comedy, making ‘Time’ also reflective of

generational changes in Indian society showing ancient traditional

beliefs and customs finding conciliation with modern technology.

The ‘foreseeing app’ of the sage ‘Rahagvan ji’ played entreatingly by

Wesleyite, Shazad Synon symbolised the modern day predicament of India

in the face of moving towards becoming a techno society; which through

comicality brings to question how much of Indian traditionalisms and

olden ways can survive without transpiring into something more

compatible with their westward modernism?

Creative veins

The jingle played over the sound system where a ‘tabla’ beat and

sitar stringing mixed chorusing of ‘Arranged-marriage-dot-com – it

works!’ in a typical Indian accent noticeably over enunciating the ‘r’

sound, every time someone mentions the ingenious website for solving the

dilemma of finding partners for young Indians, was simply a marvellous

theatrical device bespeaking the creative veins that had been at work on

the production.

Overall the production showed how a new vein of devising a theatrical

stage production could be conceptualised to fulfil the requirements of

entertainment as well as providing food for ponderous thought for those

who would like to see deeper running currents of profoundness woven in

the text of live performance, whilst not being a full length drama.

A matter of accents

There are, however, some notably accentuated points in the play where

the ‘elocutionary element’ brought out a not very naturalistic Sri

Lankan verbal output. This was most notable in the first play Sure thing

where both Bill and Betty had markedly accented dialogues. The screechy

bathroom bound bride Brenda too brought out a notable accented manner of

speech that hinted of an elocution class trained student.

Interestingly Rahul Malhotra who was played by the young actor who

played Bill in ‘Sure thing’ had switched to a very Sri Lankan manner of

speaking in English which while is very unlike the typical Indian, also

makes one wonder if Sure thing was meant to actually represent two

people in a Parisian cafe and not made to be taken in a Sri Lankan

context. In which case the question arises of whether the gamut of

complexities that were unveiled in the trial and error ‘chatting up’

scenario was actually meant to represent the western mindset?

Philip, the plainly clothed

Very clearly the young directress had a talented troupe of actors

bringing her directorial vision to life. Past Peterite Kanishka Herat

who delivered a praiseworthy performance last year in See how they run

playing the Bishop of Lax, was in a very new mould of impressive

‘agility and motion’ as Philip Glass; as were the others players in that

short play.

Yet one could not help but notice how while much attention had gone

into the wardrobe department in all actors, Kanishka, in his role,

costume wise, appeared very much the average young man going home after

office, with his sleeves rolled up. Costume wise Philip Glass was plain

and stood out in that plainness.

Beardless Trotsky

Unless some space for ‘meaning mapping’ of the character was intended

on the face of the player who brought to life the character of Trotsky,

the directress is not too likely to win the admiration of any Trotskyite

for presenting the proponent of ‘Eternal revolution’ ‘clean shaven’ and

devoid of his signature goatee and moustache. How this image defining

detail of Trotsky was overlooked in a production that evinces much hard

work and effort having been invested in art direction is rather

baffling.

The props and stage sets used served a tastefully utilitarian end.

The different sets seemed neither economically minimalistic nor showily

superfluous and evinced a very well devised and executed production from

its logistical aspects as well.

Time and Motion was a very welcoming newness to the theatre scene in

Colombo and one hopes the rousing applause that erupted at the curtain

call will resonate as a ‘calling’ to the talented group of young

artistes to further unveil their theatrical talents on stage, in days to

come. |