|

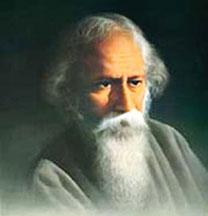

Rabindranath Tagore:

A mystic figure?

In this series on the life and times of Rabindranath Tagore and

exploring his enduring influence on Asian culture on his 150th birth

anniversary, in this week’s column, we explore the perception of his

towering personality particularly as seen in his time in the eyes of the

West. In this series on the life and times of Rabindranath Tagore and

exploring his enduring influence on Asian culture on his 150th birth

anniversary, in this week’s column, we explore the perception of his

towering personality particularly as seen in his time in the eyes of the

West.

It is well known that the West regarded him as a mystic figure,

combining his colossal personality with the Orientalist idea of the

East. However, it is pertinent to explore whether the intellectuals in

the West at the time would comprehend the philosopher and his vision for

India in general and Asia in particular. Before examining his

masterpiece Gitanjali, it is interesting to note that the Western

intellectuals had not misunderstood Tagore and his humanist philosophy

as opposed to the widely held belief that Tagore had remained a mystic

figure.

An interesting archival material that sheds light on this important

aspect of the Bengali poet and perhaps, the most celebrated Indian

cultural icon of our times is the Germany’s reaction to Gitanjali. In

Germany Gitanjali was greeted with controversy.

Primarily the controversy sprang out of inability to assess ‘the true

spirit of Tagore’s work’ in the West; “The reactionary right wing

regarded him as a Bolshevik agent and propagandist. Others, with the

narrow-mindedness which comes from a total fixation of one’s own

culture, were of the opinion that Tagore’s liberal religious

understanding was inconceivable without the Christian missionary

influence in India and held him up triumphantly as a tangible proof of

the vitality of the Christian philosophy.” Primarily the controversy sprang out of inability to assess ‘the true

spirit of Tagore’s work’ in the West; “The reactionary right wing

regarded him as a Bolshevik agent and propagandist. Others, with the

narrow-mindedness which comes from a total fixation of one’s own

culture, were of the opinion that Tagore’s liberal religious

understanding was inconceivable without the Christian missionary

influence in India and held him up triumphantly as a tangible proof of

the vitality of the Christian philosophy.”

It is stated regarding the overwhelming influence of religious poetry

on Tagore’s work and that vitality of the term ‘religion’ cannot be

realised in European context; “Tagore’s religious ideas and the

religio-philosophical content of many of his works are the reason for

the many misunderstandings surrounding his work and his person. What

earned him praise as well as censure in Europe-the religious style of

his poems-is exactly the basis of the popularity of his works in India.

Religious songs and ballads are an essential part of Indian literature

and have always had a wide circulation in their verbal form among the

public, many of whom were uninitiated into reading.

Division

Because the division between religious and secular poetry had not yet

been fully defined, the metaphors used by Tagore are drawn from

religious principles as well as worldly phenomena. The religious vein of

his poetry is not the expression of a mystic’s renunciation of the world

–something Tagore never was in his life. Heinz Mode writes in his

biography of Tagore that the connotation of the term ‘religion’ as

applied to Tagore’s work are much broader and cannot be fully covered by

the association of the world and its content in the European context. In

this religiosity there is barely a trace of mysticism that the Western

perspective and wishful thinking so often mistakenly presumes in

oriental literature. The religious element in Tagore’s writing is a kind

of visionary idealism, which arises from minute observation of the

world.”

What is interesting to note is that the same passage describes in no

uncertain terms that Tagore’s vision is not merely appreciating nature

but uses that knowledge to define the purpose of man in life; ‘while

looking at the world, it turns its gaze inward to the potential of man

within society and nature and uses the knowledge thus gained to define

man’s purpose in life.”

Tagore’s idealism was revolutionary even in his time; “The highest

ideal which Tagore envisages for human being is –to find fulfilment in

creativity and in the dedication of one’s life to the service of others,

to be loved by God who does not distinguish between his children and not

to be chained to a particular caste and its accompanying discrimination-

these postulates were courageous and much ahead of Tagore’s time. When

he gave his own son his approval to marry a widow, he sent a clear

signal how he himself put into practice his newly acquired social and

religious awareness and understanding. ”

Philosophy

In describing the difficulties that a European reader may find in

understanding Tagore’s philosophy encapsulated in Gitanjali, his vision

should be understood against the socio-economic backdrop in which Tagore

lived.“Without doubt, understanding of Gitanjali, which is Tagore’s

vision of a harmonious society, is not free from problems and

difficulties for the European reader. In our efforts to understand

Tagore’s personality and his work, we have to try to imagine what

exactly been ‘progressive’ meant in a society where feudal structures

dominated and colonial exploitation hindered its growth and development.

Tagore watched the destruction of the traditional Indian society and

realised that industrialisation according to Western formula, was not

the solution for India.

The historical contradictions during the time of Tagore came in rapid

succession. In Europe there was a gap of a few hundred years between the

Renaissance and the freeing of the country from capitalism. In the case

of India, Bengali Renaissance had begun only around 30 years before the

birth of Tagore and within a few years of his death the country threw

off the shackles of colonial rule. Tagore was a witness to all the

contradictions of his epoch and gave them permanent literary expression

in his books. ”

After 150 years from Tagore’s birth, one could clearly see how

profoundly his philosophy and literary works influenced the formation of

the cultural backbone of India and its modern outlook. Though it is

unfair to state that Tagore’s literary work and vision alone contributed

to the modern character of Indian and its organic nature of modernity,

as opposed to European modernity, it is suffice to say that India has

devised its own ‘modernity’ and ‘industrialisation’ as envisioned by

Tagore.

It is the vibrant Indian modernity which readily assimilated Indian

literature, music, philosophies and culture into its fold and has made

an effective and sustainable formula of its own industrialisation and

modernisation.

|