|

|

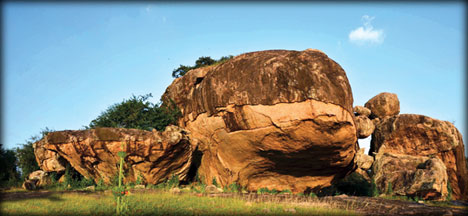

The Bovattagala rock

boulder |

Bovattagala – a cave complex in the wild

by Ranil WIJESINGHE

It is late afternoon and we can see the silhouette of trees with dead

branches jutting out against a cloudless sky. On the rock boulder, the

orange rays of the sun are reflected in the Kumana Wewa. There is a soft

hush in the air.

We climb the flat rocky terrain in Kumana through the dense jungle.

Birds including hawk-eagles and spoon-bills are on tree-tops. Suddenly,

I glimpse a hawk-eagle take wing, flying towards its prey on the rock as

we break the silence of the quiet environs. The sun starts setting over

the Kumana Wewa in a burst of orange colour.

The destination of my group was Bovattagala, about 11 kilometres

inland from the Kumana Wewa, in the southernmost tip of the Kumana

National Park. The Bovattagala crop, a huge, flat rock boulder where the

ruins of a Buddhist monastery are seen, is said to belong to the Third

Century. It contains a cluster of drip-ledged caves and a number of rock

inscriptions. From the top of Bovattagala, the endless panorama of the

Kumana Wewa and the sanctuary can be seen.

Our tracker Gayan, who has an eye for detail, takes us to the

Bovattagala site where we find an ancient flight of steps, carved out of

the rock, leading to the top of the rock.

|

|

The arrow-like cave |

|

|

An inscription |

|

|

The ruins at the site |

Today, the flight of steps is severely disfigured due to the passage

of time. We follow the same route to climb the rock as the ancient

Bhikkhus did.

On the summit of Bovattagala is an extensive area of flat rock

surface.

On the cliff of the Bovattagala rock boulder in front of the caves,

the Kumana Wewa glistening in emerald hues is a sight to behold while

the perennial carpet of trees and bushes cover the area. On the flat

rocky surface of Bovattagala, Gayan shows us two rock inscriptions and

an image of a stupa carved from the rock. From the summit, the

picturesque Kumana Wewa is visible, in the distance. The Wewa was a main

irrigation tank providing water to cultivate paddy for the inhabitants

of Kumana decades ago.

Agro-based livelihood

In ancient times, there was an anicut built across the Kumbukkan Oya

at a place called Mahagal Amuna to divert water to the Kumana Wewa to

irrigate the area. This is clear evidence that there had been an

agro-based livelihood in Kumana.

“A stupa was once believed to have stood over there,” said Gayan,

pointing to a heap of rubble on the summit overgrown with creepers.

There were ancient bricks and broken carved stones scattered everywhere,

indicating that the stupa has been demolished by treasure hunters in the

recent past.

The most striking feature of the site is the cluster of drip-ledged

caves and the Brahmin inscriptions and drawings carved on the rock

surface about 25 feet above ground. Observing the inscriptions, I

realised that they are thickly carved into the rock and the drawings

have solidity. Even today, most of these inscriptions and drawings are

clear although many centuries have passed.

The Bovattagala rock lies in a somewhat higher altitude and consists

of several caves and remnants of brick-walls around it. These caves have

been bestowed on Bhikkhus in ancient times. There is evidence that these

caves have been reused in later years. Archaeologists believe that some

of these ruined brick-walls belonged to the latter part of the Third

Century BC.

One of the caves in Bovattagala contains a drawing of an awesome

figure which looks like a ghost and has six fingers in one hand.

Archaeologists believe that it is the work of a veddah who inhabited

these caves in later years. Another cave has a drawing of a fish, giving

the impression that the site had been associated with fishing. In fact,

fishing for food started with pre-historic man and became an important

economic activity. One of the inscriptions dating from the Third Century

BC to the First Century AD is of a fish.

Since a proper archaeological survey or research has not been carried

out about the site, the history of Bovattagala is yet to be discovered.

However, some of the rock inscriptions give significant clues to the

historical background of the place. The history of Bovattagala dates

back to the Third Century BC. It was a reputed Buddhist monastery in the

Third Century BC and was venerated by the 10 noble brothers of

Kataragama, known as the Kataragama Kshathriya. These royals are

believed to have ruled the Southern and Eastern Provinces of Sri Lanka

under the regime of the King in Anuradhapura.

Jaya Sri Maha Bodhi

These princes of southern Sri Lanka took part in the festival in

Anuradhapura in celebration of the arrival of the Sacred Jaya Sri Maha

Bodhi in Sri Lanka. They had received one of the first eight plants to

shoot from the Sacred Bodhi Tree which was believed to have been planted

in Kataragama. According to archaeologists, one inscription at the site

says that the Bodhi tree had been planted in Bovattagala.

|

|

More inscriptions |

|

|

The majestic sight of

the hawk-eagle |

History also notes that kings and provincial rulers had done yeoman

service to the monastery. Another inscription indicates that the

Minister in the name of Naka, King Mahasen and King Jetta Tissa had made

various contributions to the Bovattagala monastery.

The beauty of the Bovattagala caves has been spoilt by human beings,

however, with the most horrifying sight being the names and addresses

scribbled on the rock ceiling in Sinhala and Tamil, by visitors to the

site. It is believed that these scribblings may have been carried out by

poachers or Tiger terrorists who made these caves their hideout inside

the Kumana jungle. Unfortunately, these letters are in non-erasable ink.

In addition to the main caves, there lies another isolated cave a few

feet away from the main cave, formed like an arrow with both sides open.

A little beyond this cave lies a natural pond and ruins of a stone

foundation of a huge building. The ruins of the monastery are scattered

on the summit of Bovattagala. Today, the place is deserted and lies

majestically amidst the thick jungle of Kumana, and has become home to

wild beasts.

Pix: Mahil Wijesinghe and Susantha Wijegunasekara

|