The world's first calendar found after 10,000 years

Humans had a sophisticated calendrical system thousands of years

earlier than previously thought, according to new research.

The discovery based on a detailed analysis of data from an

archaeological site in northern Scotland - a row of ancient pits which

archaeologists believe is the world's oldest calendar, is almost five

thousand years older than its nearest rival - an ancient calendar from

Bronze Age Mesopotamia.

Created by Stone Age Britons some 10,000 years ago, archaeologists

believe that the complex of pits was designed to represent the months of

the year and the lunar phases of the month. They believe it also allowed

the observation of the mid-winter sunrise - in effect the birth of the

new year - so that the lunar calendar could be annually re-calibrated to

bring it back into line with the solar year.

|

|

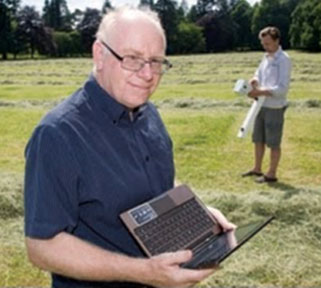

Archaeologists at the

site where a row of pits were found |

Remarkably the monument was in use for some 4,000 years - from around

8,000BC (the early Mesolithic period) to around 4,000BC (the early

Neolithic).

The pits were periodically re-cut - probably dozens of times,

possibly hundreds of times - over those four millennia. It is,

therefore, impossible to know whether or not they originally held timber

posts or standing stones after they were first dug 10,000 years ago.

However variations in the depths of the pits suggest that the arc had a

complex design - with each lunar month potentially divided into three

roughly ten day 'weeks' - representing the waxing moon, the gibbous/full

moon and the waning moon.

The 50-metre long row of 12 main pits was arranged as an arc facing a

v-shaped dip in the horizon out of which the sun rose on mid-winter's

day. There are 12.37 lunar cycles (lunar months) in a solar year - and

the archaeologists believe that each pit represented a particular month,

with the entire arc representing a year.

The 12 pits may also have played a second role by representing the

lunar month. Mirroring the phases of the moon, the waxing and the waning

of which takes 29 and half days, the succession of pits, arranged in a

shallow arc (perhaps symbolising the movement of the moon across the

sky), starts small and shallow at one end, grows in diameter and depth

towards the middle of the arc and then wanes in size at the other end.

In its role as an annual calendar (covering 12 months - one for each

pit), a pattern of alternating pit depths suggests that adjacent months

may have been paired in some way, potentially reflecting some sort of

dualistic cosmological belief system - known in the ethnographic and

historical record in many parts of the world, but not previously

detected archaeologically from the Stone Age.

Keeping track of time would have been of immense economic and

spiritual use to the hunter gatherer communities of the Mesolithic

period. Their calendar would have helped them to pinpoint the precise

time that animal herds could be expected to migrate or the most likely

time that salmon might begin to run.

But Stone Age communal leaders - potentially including Shamans - may

also have used the calendar to give themselves the appearance of being

able to predict or control the seasons or the behaviour of the moon and

the sun.

The site - at Warren Field, Crathes, Aberdeenshire - was excavated in

2004 by the National Trust for Scotland, but the data was only analysed

in detail over the past six months using the specially written software

which permitted an interactive exploration of the relationship between

the 12 pits, the local topography and the movements of the moon and the

sun.

The analysis has been carried out by a team of specialists led by

Prof Vincent Gaffney of the University of Birmingham. "The research

demonstrates that Stone Age society 10,000 years ago was much more

sophisticated than we had previously suspected.

The site has implications for the way we understand how Mesolithic

society developed in economic, social and cosmological terms," said Prof

Gaffney. "The evidence suggests that hunter-gatherer societies in

Scotland had both the need and sophistication to track time across the

years, to correct for seasonal drift of the lunar year and that this

occurred nearly 5,000 years before the first formal calendars known in

the Near East.

- The Independent

|