Drawing and painting fur and feathers

by Tissa Hewavitarane

Many people are daunted by the prospect of drawing fur because they

see the complexities first without considering how information could be

simplified.

To begin with, choose an animal that you are familiar with or work

from a photograph which will allow you to practise at your own pace. A

drawing or painting of a bird or animal without some indication of

characteristics of its fur, wool or feathers would be largely

meaningless. Therefore, the artist needs to be more inventive in this

field than in any other.

Animals and birds, unlike still life subjects, cannot be studied at

leisure. So, an extra measure of ingenuity combined with patience, is

needed even to make the preliminary observations that will enable you to

capture their forms and textures accurately.

|

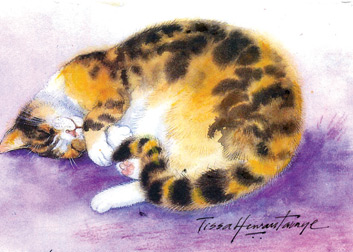

A watercolour painting of a cat |

The best way to begin is with familiar subjects. If you have a pet

dog, cat, rabbit or parrot, spend some time drawing and observing them,

try to understand the way the fur, hair or feathers clothe the forms.

Textural qualities

One of the major difficulties in drawing birds and rough-or

long-haired animals is relating the 'the top surface' to the body below,

once you can get it right you are halfway there, and can enjoy yourself

finding ways of expressing the textural qualities.

In the case of fur, light can often be very revealing. You are

unlikely to be able to deliberately light your pet as you might a still

life, but if your cat has the habit of sitting on a window sill for long

periods of time, so that it is lit from behind, study the way light

interacts with the edges of the fur and make a few drawings with chalk

or a soft pencil to see if you can capture the main tonal areas.

If the light is strong you will find that the main body of the animal

and its shadow will tend to merge together, providing an important

textural clue to the soft corona of light marking the edge of the fur.

To be able to draw or paint any complicated texture such as fur and

feathers, you must simplify the subject to some extent, which is easier

than it sounds. There is no particular recipe. But some of the following

methods might be helpful. First consider the concept of the painting.

What is it that you want to paint and why. This may seem rather

obvious, but it is sometimes easy to forget once you get involved in the

painting.

If you want to paint a portrait of your cat, for example, it would be

distracting to get too involved in some detail in the bsckground. Keep

the focus on the way the light is reflected from the fur or the special

markings and make sure all the other parts of the composition supporting

the central idea.

Even when you know what you want to paint and have got a reasonably

clear focus, like subjects present you with so much visual information

that you have to leave some of it out.

One of the biggest problems in drawing birds and animals in the wild

is getting close enough to see everything clearly.

As soon as you settle down to draw, the creature is likely to run or

fly away, so it is vital to get in the habit of sketching as rapidly as

possible. It takes some practice to make sketches that contain enough

information to use as the basis for a painting, so for the beginner it

is a good idea to start off by drawing some creature that will remain

still for long periods of time.

Observation is as important as sketching. For those who wish to draw

more exotic animals such as bears, or leopards the zoo is the obvious

place to visit and this is also the best possible place for sketching

birds such as parrots.

Your subjects will, of course, move but at least, being caged, they

will not disappear.

When you paint your dog or cat indoors or in the garden, you will

have a ready-made setting for the animal, but when your subject is a

wild creature and you are working from sketches and photographs you will

have to give some thought to the environment in which you show it.

If you look at many of the most successful animal and bird paintings

you will notice that artists take great pains to make the habitat look

convincing and achieve a lively counterpoint between the textures of the

creature and those of the surroundings.

Many will bring materials such as pieces of bark, twigs, stones or

wood to the studio so that they can refer to them while they work.

Photographs

This has the great advantage of allowing them to study shapes and

textures at leisure and choose those that make the most interesting

contrasts, but when you are out drawing or photographing wildlife it is

also worth building a visual reference file of landscape features that

might be used in a composition.

Weather-beaten wood, grass, mossy tree trunks and rough-hewn boulders

will help provide an interesting and natural-looking environment.

Rough sketches are essential and they can give a lifelike feeling to

the drawing or painting.

You will need more detailed information as well, and here the

photographs become useful. There are some who still see photographs as a

supplement to their other studies and indispensable when it comes to

drawing and painting smaller or rarer animals and birds. How ever,

photographs do have to be used with caution.

A good photograph will present a very realistic and detailed image of

the subject.

It doesn't simplify the problems, because it provides you with too

much information, giving you the job of deciding what to concentrate on

and what to leave out.

It is always best to keep a little distance between the photograph

and the painting so that it is used as a reference and does not become

the subject of the painting. |