Alfred Nobel 1833-1896

Lasting Legacy

Even today Nobel’s legacy lives on through the annual Nobel Prize

ceremonies, which are held in various parts of Sweden and Norway

annually. These awards honour the best and the brightest, who reflect

Alfred Nobel’s vision of making the world a better place! Even today Nobel’s legacy lives on through the annual Nobel Prize

ceremonies, which are held in various parts of Sweden and Norway

annually. These awards honour the best and the brightest, who reflect

Alfred Nobel’s vision of making the world a better place!

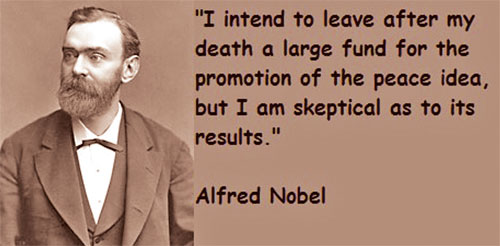

“I intend to leave after my death a large fund for the promotion of

the peace idea, but I am sceptical as to its results.”

-Alfred Nobel

His last Will

In his will of November 27, 1895 signed in Paris, Alfred Nobel

specified that the bulk of his fortune should be divided into five parts

and to be used for Prizes in Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine,

Literature and Peace to “those who, during the preceding year, shall

have conferred the greatest benefit on mankind.”

The dynamite dynamo

Since 1901, the Nobel Prize has been honouring men and women from all

corners of the globe for outstanding achievements in Physics, Chemistry,

Medicine, Literature, and for work in Peace.

The foundations for the prize were laid in 1895 when Alfred Nobel

wrote his last will, leaving much of his wealth to the establishment of

the Nobel Prize.

But who was Alfred Nobel? This article gives a glimpse of a man whose

varied interests are reflected in the prize he established.

Alfred Nobel never attended any university, nor did he obtain any

degree. His tutorial instruction came to an end as early as 1850.

While his older brothers Robert and Ludvig were busy working in the

family engineering enterprise, Alfred was sent at age 17 out into the

world on educational travels, first to Paris, where – at the

recommendation of his chemistry teacher, Prof Zinin – he worked in the

laboratory of the famous Prof Jules Pélouze. Here he came into contact

with the Italian chemist Ascanio Sobrero, who had discovered

nitroglycerine in 1847. Nitroglycerine possessed violent explosive

power, but no one had devised a solution regarding how to control this

highly dangerous substance.

Alfred’s education continued in the United States where he studied

the latest technological advances. He met John Ericsson, his father’s

countryman and contemporary who had arrived in America the year after

Immanuel reached Russia and whose interests and inventions largely

coincided with the Nobel company’s activities in St. Petersburg.

Returning from his foreign travels in 1852, Alfred joined his two

brothers at their father’s factory in St. Petersburg.

Alfred often suffered from delicate health. Combined with hard work,

this led him to fall ill in the summer of 1854 and he travelled to the

Bohemian spa town of Franzenbad to take the waters.

Together with his father, Alfred had understood the enormous

potential of nitroglycerine as an explosive and tried to develop a form

that was less hazardous and easier to handle. In testimony during one of

the American patent cases that Alfred was involved in many years later,

he explained how he and his father had become

interested in

nitroglycerine. He was asked: “Do you know of any one before you having

experimented with nitroglycerine?” interested in

nitroglycerine. He was asked: “Do you know of any one before you having

experimented with nitroglycerine?”

His answer:

“Yes, Sobrero who discovered it, also discovered that it was

explosive. Prof Zinin and Prof Trapp in St. Petersburg went a step

further in conjecturing that it might be made useful and called the

attention of my father to it, who was then engaged in making torpedos

for the Russian government during the Crimean War.

“My father tried it, but could not get it to explode.”

The next question:

“When did you first experiment with nitroglycerine, and what did you

do?”

Alfred Nobel’s answer:

“The first time I saw nitroglycerine was in the beginning of the

Crimean War. Prof Zinin in St. Petersburg exhibited some to my father

and me and struck some on an anvil to show that only the part touched by

the hammer exploded without spreading. His opinion was that it might

become a useful substance for military purposes, if only a practical

means could be devised to explode it.

My father tried to explode it during the Crimean war, but completely

failed to do so ... My father’s later experiments with gunpowder mixed

with nitroglycerine were all on a small scale.” The early 1850s were

golden years for the Nobel family. In 1853, Immanuel was presented at

court and awarded Tsar Nikolai’s Imperial Gold Medal “for diligence and

creative skill in Russian industry,” a rare distinction for a foreigner.

After the Tsar’s death in 1855 and the conclusion of the Crimean War

under the Treaty of Paris of March 30, 1856, the new government of

Russia disregarded the promises for orders made by its predecessor.

-Internet |