Sri Lanka's forgotten 4.2 %

Sri Lanka has long been synonymous with fine tea. With a plantation

history dating back to 1862 and an export value estimated to reach US$

2,500 million this year, the humble beverage is the island's pride

across the globe. Accounting for nearly 14% of the country's total

export earnings, it is among the nation's most valuable and prized

produce. Sri Lanka has long been synonymous with fine tea. With a plantation

history dating back to 1862 and an export value estimated to reach US$

2,500 million this year, the humble beverage is the island's pride

across the globe. Accounting for nearly 14% of the country's total

export earnings, it is among the nation's most valuable and prized

produce.

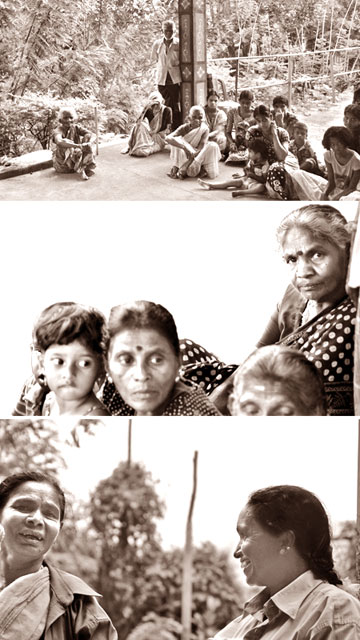

However, history has and might continue to overlook the most

important cogs in the large machine that is the tea industry of Sri

Lanka; the people without whose tireless labour this process would grind

to a screeching halt - the workers on the tea estates.

Descendants of South Indian labourers first sent here in the 19th and

20th centuries to work in the first British plantations, the 'up-country

Tamils' or 'Indian Tamils,' constitute 4.2% of the Sri Lankan

population.

Over the years, they have been marginalized by the very country that

they devote all their energy to. The Sinhala nationalism that fuelled

the Ceylon Citizenship Act of 1948 set such precise terms of identity

that even though they had lived on the island for decades, lack of

proper documentation meant they were not recognized as citizens of Sri

Lanka and left stateless.

A handful of agreements between India and Sri Lanka over next few

decades laid out plans to repatriate some, while granting citizenship to

a select few.

Finally, it was the J.R Jayewardene Government that came into power

in the 1970s that revised the Citizenship Act, adding in a Special

Provisions in the form of the Grant of Citizenship to Stateless Persons

of Indian Origin, accepting all remaining Indian Tamils as citizens of

Sri Lanka, equipping them with a nationality and a vote.

The 'line' system that exists in estate housing is the same one

established in the late 19th century - a row of small houses, each more

similar in size to a single room, that share a roof. These were

initially meant to be temporary shelters for the workers yet estate

management over the years never sought to develop the living conditions

of the workers. The 'line' system that exists in estate housing is the same one

established in the late 19th century - a row of small houses, each more

similar in size to a single room, that share a roof. These were

initially meant to be temporary shelters for the workers yet estate

management over the years never sought to develop the living conditions

of the workers.

Each family is allocated one of these 'houses', meaning everyone

lives in uncomfortably close quarters, severely distorting family

dynamics. Should a child marry, reproduce and come to live in his/her

parents' house, as it does frequently happen, the situation worsens.

No address

Yet the estate worker is not the owner of his house, even though it

is that small. Since the plantation land belongs entirely to the estate,

the worker is not provided with a deed or permit that proves that the

house is his/hers. Should he plant a tree outside the line, even its

fruits would technically belong to the estate management.

Because of this system, where the housing comes under the control of

the management, individual houses are not provided with an address. This

results in administrative issues, problems for the police and issues

during voting.

The lack of an address also means important correspondence doesn't

reach the house - all mail must be addressed to the estate's head office

and is distributed at the management's convenience. Workers don't

receive time-sensitive EPF notices, students who persevere enough to

complete their AL education don't receive their university letters in

time and most personal correspondence never reaches the person it was

meant for.

Estates, being private lands, do not fall under the Pradeshiya Sabha

Act therefore local authorities do not have the power to provide

addresses in these areas as the roads too are the estate's property;

their maintenance is the responsibility of the estate.

This feeds into a range of obstacles in the worker's daily life.

Walking from their line house to the particular area of the plantation

they are required to work at, both places sometimes on two different

hills, is laborious enough without the badly-maintained road. The walk

back after a day's backbreaking work is hellish.

Classes in estate schools are limited and students who wish to study

further have to go into the main town. Hospitals, long since neglected,

are not adequate for all emergencies and again, they are forced to

resort to services in the town. Access to these are made additionally

time-consuming because the roads are so badly damaged and the limited

bus services available to estates are irregular.

Estate schools extend to Grade 5 or Grade 9 in most cases and

students who wish to study beyond that resort to making the journey from

the estate to the closest city to complete their education. Kids

talented in sports or the arts don't have as many options for

progression in their fields as a child in the town would. While most

schools would employ teachers who are specialists in their subjects to

teach children, some of the young women appointed to estate schools only

have the Advanced Level qualifications.

Though there are hospitals buildings in the estates, most of them

have fallen to disarray after years of neglect and those that do

function, can only administer treatment for the most basic ailments.

Surgeries and delivery of babies has to be done by trained doctors in a

town hospital.

Health issues are constantly mounting in the cramped living

conditions. A single line with five or so houses share a wall and with

more than five people living in a single room, contagious diseases

spread rapidly. In addition, most estates don't have a proper toilet

system for the inhabitants of the line houses to use. Health issues are constantly mounting in the cramped living

conditions. A single line with five or so houses share a wall and with

more than five people living in a single room, contagious diseases

spread rapidly. In addition, most estates don't have a proper toilet

system for the inhabitants of the line houses to use.

No options

Water distribution in some plantations is such that the same water

used by lines higher up the mountain makes its way down a channel to the

lower divisions and the individuals there are left having to use water

that is far from pure. Even in places where this particular system is

not used, irregular water distribution methods and lack of basic hygiene

facilities contribute to prevailing health dilemmas.

The options available to women who wish to work outside the estate

are very limited. Aspiring to reach greater heights than the generations

before them, idealistic women look for jobs in Colombo - working in

someone's house or in a garment factory.

Their other option is to look for labour work abroad, which they

sometimes find difficult to adjust to because of the culture

differences. Eventually, most of them return only to marry and begin

their own families and start, inevitably, working on the estate.

Though some do make these journeys, some fall into the cycle of the

culture and are married as soon as they come of the legal age. Young

brides bear children at a young age and are thereby compelled to stop

schooling to take care of and provide for the children.

The consumption of alcohol by men, to beat the cold of shivering

temperatures around the mountains and as an antidote to a day's hard

work, has resulted in an increased number of cases of violence against

women and children.

This habit has spread among the women too. Because the communities

consume illicit alcohol that is not manufactured properly, sickness

results.

Lack of documentation

To approach the relevant authorities that could possibly help address

their concerns is also difficult for the workers; even though the

communities are Tamil, government agents appointed to offices in these

areas are mostly Sinhala and the language barrier creates more

confusion. Police stations, hospitals and other entities working

directly with the people are not able to communicate using the language

of the region's majority.

This is one of the many factors that contribute to lack of proper

documentation in the estate communities. Birth certificates are not

issued or don't carry accurate information, individuals do not have

national identity cards and when couples marry, they do not seek to

obtain a marriage certificate. Lack of awareness of the administrative

procedures due to being cut off from society reinforces these inactions.

However, superintendents hold back in giving work, asserting that the

leaves are not yet ready for plucking; this means some workers can't

fulfill the quota and thereby have their pay reduced. Estates have taken

to hiring workers on a 'temporary' basis, where they are paid by the

kilogram at a rate that is much lower than the wages of the permanent

worker; all far too little considering the harsh working conditions and

the denial of any other labourer benefits to the workers.

Over the years, the estate Tamils have been a community marginalized

by the state and mistreated by the corporations that employ them.

The distance from an estate to the nearest town and the tight working

schedules helps the estate management to keep them cornered from and

uneducated about society.

Unions, who should be advocating worker's demands for benefits, shy

away from their responsibility due to political influence.

These workers have not been made aware of the benefits they should be

receiving as employees and rights they are able to exercise as citizens

of Sri Lanka.

Story and pix: Centre for Policy Alternatives

|