Can you own a colour?

How would we market the shades favoured by famous artists? Following

British Petroleum's (BP) failed bid to trademark green, BBC's Fiona

Macdonald checks out the pigments of great painters.

The oil company BP lost its battle to trademark the colour green in

Australia - but other brands around the world have managed to claim

particular shades as their own: US jeweller Tiffany has the sole legal

right to use its signature blue and purple has been commandeered by pet

food company Whiskas in Australia.

From Titian red to Yves Klein blue, some shades are immediately

associated with particular artists. With the help of experts from the

National Gallery and Tate Modern in London, BBC has picked out seven

hues that have taken on particular meanings for painters in different

schools, from Renaissance Masters to Russian abstract art pioneers.

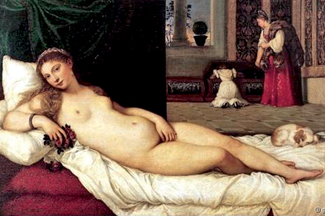

| Realgar: Titian

Although

artists had mixed red and yellow to make orange in Medieval

paintings, a pure pigment was sought. The mineral realgar

was used in 16th Century Venetian and Dutch flower

paintings, but it had one drawback - it contained arsenic. "Realgar

produced a really bright orange, but was poisonous," says

Campbell. Despite this, the Venetian painter Titian was

partial to the pigment, using it to tint the tresses of the

women in his paintings a particular shade that is now a

popular hair dye (and even inspired a range of Barbie

dolls). "Titian red was a phrase that was coined in the 18th

or 19th Century for looking at the hair of the women he

painted - such as the Flora in the Uffizi Gallery, or the

Venus," says Campbell. Although

artists had mixed red and yellow to make orange in Medieval

paintings, a pure pigment was sought. The mineral realgar

was used in 16th Century Venetian and Dutch flower

paintings, but it had one drawback - it contained arsenic. "Realgar

produced a really bright orange, but was poisonous," says

Campbell. Despite this, the Venetian painter Titian was

partial to the pigment, using it to tint the tresses of the

women in his paintings a particular shade that is now a

popular hair dye (and even inspired a range of Barbie

dolls). "Titian red was a phrase that was coined in the 18th

or 19th Century for looking at the hair of the women he

painted - such as the Flora in the Uffizi Gallery, or the

Venus," says Campbell. |

International

Klein Blue: Yves Klein International

Klein Blue: Yves Klein

While lounging on a beach with friends in

1947, a 19-year-old Yves Klein reportedly gazed up at the

sky, imagining his signature next to the clouds, and

declared "the blue sky is my first artwork." The French

artist went on to patent his own unique shade of blue in

1961 and moved away from creating the paintings himself,

instead directing naked models covered in the colour as they

walked, rolled and sprawled on blank canvases. |

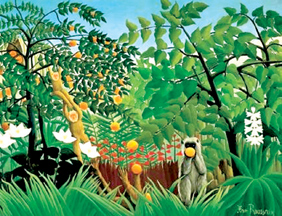

Viridian:

Henri Rousseau and Paul Cezanne Viridian:

Henri Rousseau and Paul Cezanne

What did you do if you were a 14th Century

painter, and you wanted to depict a tree? One unexpected

problem encountered by nature-loving Renaissance artists was

a degradation of pigment, leaving them with bizarrely

coloured landscapes centuries later. "Previously, painters

were often mixing blue and yellow together, and often the

yellows were unstable and so the greenery is now blue," says

Caroline Campbell, the co-curator of the exhibition Making

Colour at London's National Gallery.

"Landscapes weren't really painted until

the 16th and 17th Centuries; it's a genre of painting that

didn't exist before, so there wasn't such a desire to find

green pigments. But by the 19th Century, when Rousseau and

Cezanne are painting largely as landscapists, they have

these new manufactured pigments that are rich in colour and

also very stable: emerald green and viridian. Suddenly you

have these landscapes which can be green, and stay green."

|

Chrome

yellow: Vincent Van Gogh Chrome

yellow: Vincent Van Gogh

"People associate yellow with Van Gogh,"

says Campbell. "He said that yellow is the colour of

happiness ... and it's the colour of so many of his

paintings between 1880 and 1890." Doctors believed that the

Dutch painter suffered from epilepsy, prescribing him the

drug digitalis - which can cause users to see in yellow.

High doses of the chemical thujone can have a similar

effect: the toxin is present in absinthe, which Van Gogh

drank regularly. "At this really intense period in the

summer of 1888 when he's painting the sunflowers, yellow

really is the colour of happiness," says Campbell. "But that

changes, and by the end of the year when he's cut off his

ear and his relationship with Gauguin is gone, it's

interesting that his self-portrait with a bandaged ear is

also in yellow. Maybe it's because he's thinking about a

moment in his life in which he was very happy." |

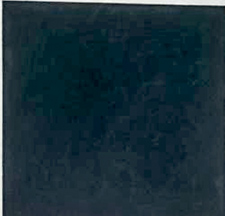

| Black: Kasimir Malevich

Renaissance

painters produced their blacks by burning bones or ivory,

collecting soot from oil lamps and grinding charred grape

vines. The colour was long associated with death - but one

painter gave it a different spin in 1915. When Kasimir

Malevich painted his first Black Square, he launched a new

movement, Suprematism, and liberated art from the

figurative. Renaissance

painters produced their blacks by burning bones or ivory,

collecting soot from oil lamps and grinding charred grape

vines. The colour was long associated with death - but one

painter gave it a different spin in 1915. When Kasimir

Malevich painted his first Black Square, he launched a new

movement, Suprematism, and liberated art from the

figurative.

It "brought an end to centuries of

representation and marked a zero hour in modern art"

according to Achim Borchardt-Hume, the curator of Malevich:

Revolutionary of Russian Art at London's Tate Modern. It

also became a personal motif for the painter: when he died

in the Soviet Union in 1935, mourners waved banners with

black squares; his burial site was marked by a black square

on a white cube. "Within months of Malevich's death, his art

was banned from public view and the Black Square was not to

find its way back onto display until the early 1980s." But

the dark hue marked a new beginning: "For Malevich, it was

the starting point for a wholly new approach to art, wiping

clean the slate of conventional notions of image

construction." |

Mauveine:

Royal portraitists Mauveine:

Royal portraitists

Purple, the traditional colour of royalty,

was given a twist in 1856 when the English chemist William

Perkin accidentally produced the first ever synthetic dye,

mauveine. Perkin's shade of mauve received a royal seal of

approval in 1862, when Queen Victoria appeared at the

International Exhibition wearing a silk gown dyed with

mauveine and brought the colour into vogue. In a set of

photographs, she and her family are shown in dresses in this

colour - the pictures were hand-painted with a coloured wash

made from the dye. "When I think of Victorian England, I do

think of purple as being one of the colours associated with

it," says Campbell. "Suddenly this colour that was the

colour of royalty could be really easily and quickly

produced." |

Green

earth: Renaissance Masters Green

earth: Renaissance Masters

Italian painters often used the mineral

clay pigment as an underlayer when painting skin. It

neutralised reds and pinks, which could appear fiery when

applied to wood panels - but with the passing of time it

lends an unfortunate complexion. "The problem is that often

the top paint layers faded over centuries, and now these

faces sometimes have a rather sepulchral greenish tinge,"

says Campbell. The pigment has given greenish tinges to the

faces of the Archangel Gabriel and the Virgin Mary in

Ducci's The Annunciation and to the neck of the woman in

Vermeer's Guitar Player. |

|