|

DRAMA

Facing recollection and seeking closure

A review of the drama 'Forgetting November' :

by Dilshan Boange

What currency do memories have without a 'tangible' stamp of

authority to its authenticity? One might say, this is where the 'past'

conflicts with 'history'. Reminiscence is thus a vehicle with which the

'past' can be accessed, while history stands to claim its

'accessibility' as a 'legible record'. But creating 'monuments for

remembrance' is an act that can perhaps serve as stimuli for personal

reminiscence while also being a record for history. Whose purpose does

memorialisation ultimately serve? Without evidence of records, are

memories just as vulnerable to being dubbed imagination? These are some

of my thoughts after watching the play 'Forgetting November' at the

Harold Peiris Galley of the Lionel Wendt Arts Centre, late last month. What currency do memories have without a 'tangible' stamp of

authority to its authenticity? One might say, this is where the 'past'

conflicts with 'history'. Reminiscence is thus a vehicle with which the

'past' can be accessed, while history stands to claim its

'accessibility' as a 'legible record'. But creating 'monuments for

remembrance' is an act that can perhaps serve as stimuli for personal

reminiscence while also being a record for history. Whose purpose does

memorialisation ultimately serve? Without evidence of records, are

memories just as vulnerable to being dubbed imagination? These are some

of my thoughts after watching the play 'Forgetting November' at the

Harold Peiris Galley of the Lionel Wendt Arts Centre, late last month.

Written

and directed by Jake Oorlof of Floating Space Theatre Company the

production was supported by Groundviews, the online citizens' journalism

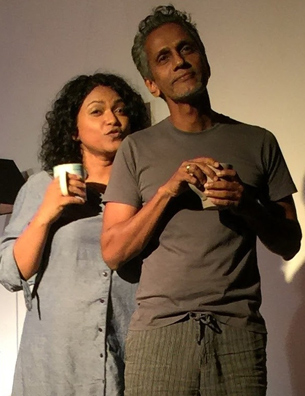

forum. The cast consisted of veteran actor of the stage and screen Peter

D'Almedida, theatre practitioner and academic Ruhanie Perera and reputed

arts promoter Ranmali Mirchandani.

Forgetting November was not staged as a proscenium show. Observing in

closer proximity was the principal factor that created the nexus of

intensity with the audience. However, the players were fixed on, what

was to me, a noticeably theatricalised form befitting the proscenium.

Thus it was perceptibly proscenium theatricality though physically out

of the proscenium.

Ruhanie Perera seemed conscious of the audience during the opening

scene. There was a noticeable 'woodenness' in the dialogues between her

and Peter D'Almeida, which however thawed as the play progressed. The

same could be said of the initial dialogues between D'Almeida and

Ranmali Mirchandani. But the actors seemed more in an eased gear of

performance in their solo moments, like for example Mirchandani's

monologue, or Perera's solitary moment of washing herself in the living

room. From a theoretical perspective, one may ask how effectively

'Forgetting November' broke the 'fourth wall'. My observations say it

did not undeniably redefine the 'space of performance' to create a new

propinquity between the viewer and the performer.

Cultural setting

The set was tastefully done. The decor showed no incongruity with the

performance venue and its physical space. Among the pictures hanging on

the wall I observed one that was a black and white daubed brush painting

distinguishing to the discerning eye Don Quixote on horseback and Sancho

Panza mounted on his donkey complete with the windmills. A subtle item

of identification of the cultural setting the story geographically

unfolds in, one may assume. The story is set in a fictional Latin

American country.

Perera's performance peaked at the point her character recollects the

run in with her torturer and the consequent emotional whirlwind that

erupts. It was a compelling delivery of the recurring agony silently

suffered by a victim of repetitive rape and physical torture. Unlike

memories of sweetness, the memory of pain is pain itself.

Among the issues debated are the monument by the government for the

fallen rebel leader 'Thiago', and the decision of the character played

by Perera to give evidence at a hearing of a commission for truth and

justice.

Meaningful closure

Perera's character says she recognised the army officer who was in

charge of the camp in which she was tortured, after running into him

accidentally in a hotel years after the ordeal. But he simply didn't

recognise her. And that speaks of how in a different time and space the

circumstances created a context that her identity was completely

different in the eyes of her former captor. Our individual identity at

times depends largely on what others remember of us. Context can

determine who we are to whom and what our 'identity' may be at a given

moment in time. When 'spaces' change, identities of individuals too can

get shifted and even get sifted.

"There is no shame in sweat. It's an equalizer," says Mirchandani's

character quoting her former rebel leader and lover Thiago. But she

herself admits to using 'hand cream'. So how much does that character

reflect her former self apart from her memories? "There is no shame in sweat. It's an equalizer," says Mirchandani's

character quoting her former rebel leader and lover Thiago. But she

herself admits to using 'hand cream'. So how much does that character

reflect her former self apart from her memories?

One of the central issues in the story is the purpose and merit of

the commission created to investigate crimes committed by government

forces.

The former rebel played by D'Almeida says it's "opening a window to

close a door." Do commissions on war crimes actually bring

reconciliation and meaningful closure, or are they merely token gestures

that become routine and redundant with prolonged denial of concrete

conclusions playing on a promise that eventually justice may be

delivered?

During my undergrad days the Czech novelist Milan Kundera's The Book

of Laughter and Forgetting showed me how the 'past' relies on both

individual and collective memory to stay alive, while 'history' is a

record sanctioned by state authority. As a teenager I got my first

notion of how the 'past' and 'history' can be differentiable, from what

was spoken by the character of a Native American elder of the Navajo

tribe on an episode of The X-Files. I rediscovered that text from my

collection of 'X-Files literature'. Page 148 of The X-Files, Book of the

Unexplained by Jane Goldman Vol. 2 (1996) contains that narrative. I

have produced here an excerpt-"There is an ancient Indian saying that

something lives only as long as the last person who remembers it. My

people have come to trust memory over history. Memory, like fire, is

radiant and immutable while history serves only those who seek to

control it, those who would douse the flame of memory in order to put

out the dangerous fire of truth."

Forgetting November is a significant work of post-war literature/art

in Sri Lanka in the medium of performance. Issues relating to both the

JVP insurrections and the war in the North can find connections with

this play's narrative. When monuments are erected newly and old ones are

torn down and memorialisation becomes state crafted 'remembrance',

irrespective of which regime holds the reigns, what finally, is 'the

truth' passed to posterity? From whichever angle you look at it,

finally, the truth of the matter is that history is the prerogative of

the victor.

Pix by Sanjana Hattotuwa |