|

|

| |||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

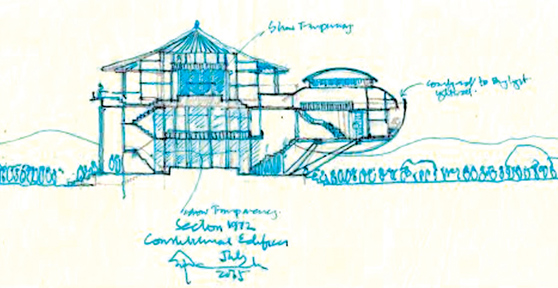

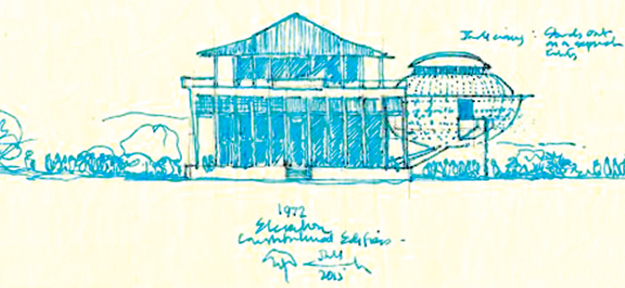

Connected to this was an interest in the Constitution as an enabling (or in the case of Sri Lanka, enervating) idea. The process through which the heinous 18th Amendment came to pass was deeply instructive in how through the manipulation of discursive spaces, the spread of misinformation, the shrill drowning out voices of caution and reason and in a context of fear, with mainstream media controlled by partisan and market driven interests, expedient parochialism was seen as somehow benevolent and necessary. Interrogating the ConstitutionTwo years after the 18th Amendment, my first attempt to interrogate the Constitution through architecture was in 2012 with ‘Mediated’ – an exhibition that focussed on research driven art – and was anchored to the depicting the power-sharing in pre-British Sri Lanka as a viable model for devolution of power, post-war. The output was a collaboration between architect Sunela Jayawardene and Asanga Welikala, a constitutional lawyer and close friend from the halcyon days of S. Thomas’ College, Mount Lavinia. My second attempt was in 2013, and involved Sunela again. As part of the ‘30 Years Ago’ exhibition, a triptych by her portrayed key developments and individuals three decades after the events of ‘Black July’, using Google Maps imagery on Jaffna, Colombo and elsewhere as the base layer. Though compelling and critically acclaimed in their own right, I yearned for a more finely matched interrogation of Sri Lanka’s constitutional evolution through architecture. Architecture is for me a dark art - making small spaces seem larger than they are, harnessing the chiaroscuro within a building to influence the mood of inhabitants, enabling access to spaces, barring access to others, creating secret pathways, chambers and shortcuts purposefully or inadvertently, giving the illusion of openness, when in fact inhabitants are boxed in, or conversely, freeing up a claustrophobic space with just slivers of open sky. If architects were the gods of spaces they created, I wondered, could the same be said of those who drafted our Constitution? A Constitution is essentially a blueprint of power relations. Architecture – drawing, rendering and modelling – provides a blueprint of spatial relationships. This exhibition is not a study in how and to what degree (State or authoritarian) power influences the design of edifices. It is rather an attempt to use the visual and spatial expression of architecture to visually depict as well as deconstruct loci of power as enshrined in our Constitution. Lanka’s constitutional evolutionWhat, I imagined, would a corridor that connected a central hall to a room far in the periphery look like? How many people could fit into these corridors? What would the President’s room look like? Would it be large and grandiose with thick walls and few windows? How would someone access the Supreme Court? What would Parliament look like? What would the rooms and offices within it be like – porous walls that allowed conversations from adjacent spaces to seep in, a catacomb of doors, some mysteriously locked, to access what was otherwise a stone’s throw away? How large would the main halls be, and how cramped would be the periphery’s accommodation?

The exhibition clearly demonstrates the futility of even more amendments to a constitution that since conception 1978 was deeply flawed. It highlights the outgrowth of authoritarianism, and the illusion of stability. It gives life to the phrase, ‘the centre cannot hold’. Through errors thrown up by the architectural programme Autodesk Revit, significant flaws of our present constitution are clearly flagged. The models will collapse over time. The drawings are increasingly grotesque. The architectural output makes abundantly clear the failure of our constitutional vision. All this, we countenanced. All this, we could have opposed. All this, we voted in, defended or were silent about. Invitation to reflect‘Corridors of power’, as with all my exhibitions previously, is an invitation to reflect on what we have been hostage to in the past in order to imagine a more just, inclusive, open future. Spaces to meet, reflect and react, need expansion. The checks and balances of power need firmer foundations. Centripetal tendencies in design must be eschewed in favour of centrifugal development. We need open spaces instead of closed sites, grass to walk and play on instead of just to admire. Easy access to key locations. Light, more than shadow and shade too, where needed. In sum, we need to be the architects of the change we want to see. It is the essence of citizenship. It is what gives life to a constitution worth having. Worth knowing. Worth defending.

|

|

|

|

|

|