The Elephants in the Room

|

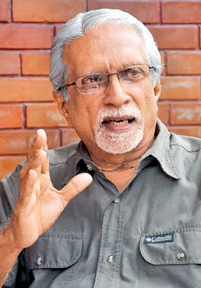

Jayantha Jayawardene

|

Take a small-sized developing island nation. Sprinkle in some

depleting jungle habitat. Now add five thousand elephants to the mix.

Jayantha Jayawardene, founder of Sri Lanka's Biodiversity & Elephant

Conservation Trust, tells Pranav Capila, consulting editor with the

Wildlife Trust of India, the dangers of stirring such a pot.

Q: You were, I believe, a tea planter at one point of time.

What drove you to work with wild animals? A: I have been interested in

animals since I was a child. And I was fortunate to have that interest

nurtured at school -Trinity College - where I was a member of the

Natural History Society. It was just a bit of bird watching, hiking and

camping once in a while, but it made a big impact on me at that young

age.

Later, as a tea planter, I began camping out a lot in various

wilderness areas around Sri Lanka. I grew closer to wildlife, elephants

in particular. I took detailed notes when I was out in the wild,

observing elephant behaviour, seeing how they interacted with one

another.

Q: I read an article in the Asian Wall Street Journal, dated a

decade ago, which quoted you as saying that Sri Lankan elephant numbers,

unique to Asia, were on the rise. What is the current status?

A: Elephant numbers were depleted at the time and were on the

rise. They now seem to be steady at about 5500, neither increasing nor

declining significantly.

One reason why people may believe that the numbers are still rising

is the large number of baby elephants we find in Sri Lanka annually.

However, there are no studies to determine whether these babies ever

reach maturity. You see, from the time they are weaned to the age of

about eight or nine years, elephants have to compete for food with

ungulates such as deer. It is only when they grow bigger that they can

reach food sources that are not available to smaller herbivores.

Q: Especially on a small island, a developing nation where the

competition for land is acute, doesn't a large elephant population

exaggerate human-elephant issues?

A: There are three facets to these issues. One is that man is

intruding into elephant habitat: the increase in human population means

that more land is required for agriculture, settlements, development

etc. That reduces the wilderness area available to elephants - and you

may know that the elephant is an umbrella species; by protecting

elephant habitat you conserve the habitat of a number of other species.

The second point is that the clearing of jungles is being done ad

hoc. The different government departments involved in development

activities take chunks of jungle land from wherever they please, without

coordinating with each other. Not in a planned way where smaller but

contiguous portions of jungle could be left intact. The result: elephant

habitat is fragmented, which means that elephants have to travel through

human inhabited land to get from one habitat to the other.

The third point is that elephants are smart enough to have realised,

over the years, that the food humans grow is highly nutritious. Asian

elephants would usually walk 10-20 kilometres a day to find sufficient

food. Now they come to human cultivations, which are like supermarkets

to them!

Q: In your talk at the Minding Animals Conference (hosted in

New Delhi by the Wildlife Trust of India) you said 'conflict' is a

one-sided, human centric version of events: it is 'conflict' when

elephants hurt human interests, not when humans hurt elephant interests.

But how do you sell conservation to people for whom elephant control is

quite literally a matter of life and death?

A: I have undertaken two comprehensive surveys in areas of

human-elephant conflict around Sri Lanka. I stayed in the villages in

these areas, talked to the people there. And if you ask them whether

they want the elephants killed, they say no, just get them out of our

way, away from our crops.

Q: What's the way forward? I read press reports that suggested

there was some talk of exporting Sri Lankan elephants to Vietnam, Laos,

Malaysia?

A:

Well, Sri Lanka is a CITES (Convention on International Trade in

Endangered Species) signatory, so such reports are not founded in

reality. It's a question of planning. We have to realise that 70 percent

of the elephants in Sri Lanka live outside our national parks - which

also increases the incidence of conflict. So at some point of time we

have to demarcate the elephants' home ranges, both inside and outside

the parks, as protected areas. A:

Well, Sri Lanka is a CITES (Convention on International Trade in

Endangered Species) signatory, so such reports are not founded in

reality. It's a question of planning. We have to realise that 70 percent

of the elephants in Sri Lanka live outside our national parks - which

also increases the incidence of conflict. So at some point of time we

have to demarcate the elephants' home ranges, both inside and outside

the parks, as protected areas.

Another solution wherever we have intermingling of elephants and

humans is to have what we call 'managed elephant reserves,' which place

an emphasis on maintaining elephant corridors.

Q: I believe the Sri Lankan Government has mulled a policy to

capture 'troubled' elephants and use them for cultural performances,

industry etc?

A: Well, Sri Lanka has a requirement for tame elephants,

because they are used in temple ceremonies and the like. The number of

tame elephants is depleting, however, since there is very little captive

breeding. One reason is that elephant owners don't like to have their

female elephants 'out of commission' - as they would be when they are

pregnant. Second, baby elephants are seen as a resource drain because

they are not income worthy till the age of about ten years.

The government used to issue special permits to families that had

traditionally raised elephants, allowing them to capture elephants from

the wild. This was stopped in the 1970s since wild populations were

depleting.

My suggestion to the government of Sri Lanka - I spoke to several

ministers about this - was to capture and train elephants that are

designated 'troubled'. Such elephants are reported by villagers to the

Department of Wildlife Conservation and are thus easily identified;

instead of shooting or poisoning them they could be captured and tamed.

They could then be given to owners that are registered with the

department of wildlife and have been deemed capable of the care and

upkeep of such elephants.

The government did actually start a pilot project along these lines.

However, when they invited potential owners, about 200 to 300

politicians put their own names forward. So the idea had to be shelved;

it has been in limbo for the last five years. It's unfortunate, but that

is the nature of the political class in most countries, I imagine!

(This interview was originally published in

Sanctuary Asia, August 2015, www.sanctuaryasia.com.) |