|

observer |

|

|

|

|

|

OTHER LINKS |

|

|

|

The kite runners of Lahore

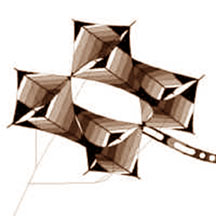

Lahore wakes up in spring. Warm breezes roll through Pakistan's proudest, most cosmopolitan city, and inspire a brief, intense season of weddings and parties before the massive, deadening heat of summer. And if there is a symbol of this busying, quickening time of the year, it is the kite. Not one, but thousands, a mad flock flying above the city. Don't be confused. The kites of Lahore are not the kites of London, or the Lake District. They are not plastic or flown in isolation by serious-looking people in the park, holding onto tough nylon lines and steady, well-made handles. They are kites flown in the ways of the north Indian, Pakistani or Afghan: where the aim is not so much a Mary Poppins moment but the peitch, the cutting of your neighbour's kite out the sky and claiming it. Kite-flying in Lahore, which culminates in the annual festival of Basant, a 24-hour binge of battling shapes, is a communal, noisy event, where people climb onto the roofs of their houses, cook, eat, dance and compete with each other. It is the same sport as described in Khalid Hosseini's 2003 novel The Kite Runner (to be released as a film in 2007), only more so. Sports in their bloodLahoris claim that the sport is in their blood, a part of who they are. An otherwise calm psychology professor in the city explained it to me this way: "It's a unique game. You do not fly the kite, you fly yourself. It is a sensational game." He went on: "It's mood and spirit has always been the same: to defeat your competitor and celebrate with a loud voice, this is the Punjabi way."

A walled city that was for centuries a hub of political and artistic power, Lahore sits on the old Grand Trunk Road that joins Kabul and New Delhi and used to be known as the Paris of India. Nowadays it sits on the border of Indian Punjab, 54km from Amritsar, and is the undisputed cultural capital of Pakistan: the home of its newspapers, publishing firms, fashion houses and Lollywood, the country's nascent film industry. If you can see past Lahore's extraordinary traffic - a kind of perpetual swerve of motorbikes, donkeys, buses, tiny Japanese cars and, occasionally, bigger Western ones - you can read the city's history in its streets. Extra ordinary trafficIn the north-east corner there is the old city, a tight, brown, spaghetti of bazaars and crumbling buildings, overseen by the magnificent fort and Badshahi mosque, built by the Mughal emperors of the seventeenth century. Spilling out of the walled city is a succession of orderly, British avenues, which are lined with trees and Lahore's major institutions: its railway station, post office, courts, provincial assembly and museum, all built in the striking Mughal-colonial style. There is a mixture of time standing still and moving decidedly on. The Mall, its name unchanged, remains the central artery of Lahore and still holds the Zamzama, the talismanic cannon made famous by Rudyard Kipling's poem of the same name. But the streets are lined with billboards and news tickers now, and the platform outside the Punjabi Assembly that used to carry a statue of Queen Victoria holds a glass-cased Koran and a collection of gifts from the 1974 world Islamic conference. When I arrived, Lahore's traffic also spoke of the coming of the kites. The commonest form of transport in the city is the Honda motorbike - normally emblazoned with a tough-sounding slogan, like "Death Game" or "Fly Racer" or (my favourite) "Cash Deposit" - and many of these had been rigged up to protect their riders from kite strings. Motorcyclists had patched together aerials and strips of piping to make loops from their handlebars to their exhausts so stray kite strings hanging across the road wouldn't catch them by the neck. DiscoveryAnd this was my discovery over the coming days, that kite-flying in Lahore, like many hugely popular, competitive sports, had become complicated, lethal and very controversial. It comes back to the pitch. The desire to slice through the strings of all the other kites in the sky has fuelled an unhealthy hunger in Lahore for ever sharper and even corrosive strings. The kite stringKnown as dur, kite string has for a long time come in a bewildering range of sizes, lengths and degrees of edginess. Once you know that length is measured (simultaneously) in "pieces", "Goths" and yards (three pieces equals seven-and-half Goths equals 2,000 yards), you get the picture. But in the last few years, dur has evolved to bring new, modern dangers: threads covered in glass powder, coated in acid or reinforced with metal. When these strings fall, they entangle in Lahore's electricity supply and hang, dangerously across Lahore's busy roads. In the weeks leading up to this year's Basant, seven people, including a three-year-old girl and a four-year-old boy, both riding as passengers on motorbikes, were killed by the strings. Last year, 24 people died in similar accidents. The legend The kites are also seen as responsible for moral dangers. Basant, derived from the Hindu word Bassand, is a secular, Indian festival in which, as the legend goes, the kites are supposed to represent the swaying of mustard flowers and so the coming of spring. As a non-lslamic event that is associated with loud music, eating and drinking, it has always attracted the criticism of ascetic Muslims. In recent years, the increasingly corporate nature of the festival - large Western and Indian companies tend to hire roofs in the old city to watch the kite-flying - and the hazards of the newer kite strings have only added to the unease. Syed Muhammed Abba, a teacher in a Shia madrassa, told me that the festival was a symptom of Lahore's moral decline. (Courtesy:www.timesonline.co.u |

Sam Knight visits the Pakistani city in time for the annual

kite-flying festival - only to find attempts to crackdown on the time-honoured

sport.

Sam Knight visits the Pakistani city in time for the annual

kite-flying festival - only to find attempts to crackdown on the time-honoured

sport.  I arrived in Lahore earlier this month, a few days before the start

of Basant, which usually opens as darkness falls on a Saturday night in

late February or early March.

I arrived in Lahore earlier this month, a few days before the start

of Basant, which usually opens as darkness falls on a Saturday night in

late February or early March.