|

observer |

|

|

|

|

|

OTHER LINKS |

|

|

|

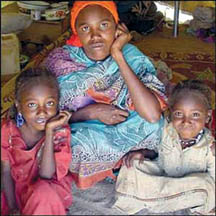

No end in sight to Darfur troublesIt is over three years since Darfur first came to the attention of the Western world. Back in the summer of 2003, television viewers watched in horror as images of burning villages filled their screens. "Janjaweed" militia backed by the Sudanese government were on the rampage.

Humanitarian effortWorld leaders, Oscar-winning actors, even Olympic sportsmen came to take a look at a human catastrophe on a vast scale. Three years on, the names of some of the rebel movements have changed, but overall the picture is depressingly similar - the Sudanese government is bombing villages in Darfur while rebel forces fight a guerrilla war on the ground. The feared "janjaweed" are still around, but the government have now enlisted another junior partner, in Minni Minnawi's former rebel Sudan Liberation Army faction. Large areas of Darfur are now off-limits to both the aid community and African Union peacekeepers. Without impartial observers, no-one is able to report back on exactly what is taking place. The evidence from the injured and those fleeing points to a large government offensive aimed at rebels factions who refused to sign May's peace agreement. These rebels have formed an umbrella group called The National Redemption Front and have had some military success, most notably taking the town of Um Sidir. The government has retaliated from the air, bombing four areas in north Darfur. There is no precision targeting in the Sudanese Air Force. Bombs and other improvised devices are rolled out of the back of the cargo door, onto the ground below.

Instead of the other rebel groups being gradually pressured into joining the agreement, the opposite has happened. Public opinion in Darfur has crystallised against the DPA and commanders appear to be leaving the deal, rather than joining. Khartoum now claims it inhabits the moral high-ground, fighting in the name of peace. Faced with such a violent mess, the UN peacekeeping force has been promoted as the solution to Darfur's problems. The current African Union mission has struggled with 7,000 men so a better-equipped force, three times the size, has been proposed. Resolutions from both the UN Security Council and the African Union have called for a transition to take place. RhetoricBut, faced with mounting international pressure, Sudan has shown about as much flexibility as a brick wall. Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir has dubbed the UN mission re-colonialisation and offered to resign and lead the armed resistance himself. Sanctions have been threatened as a means of persuading Khartoum to change its mind but on the back of rising oil exports the Sudanese economy is booming. American or European sanctions would undoubtedly hurt but Sudan still has good friends in the Middle East and most of the country's oil is bought by China, which has a less than perfect human rights record. There are already 10,000 UN peacekeepers deployed in the south. So, for many Sudanese, a quiet transition from UN to AU would hardly have raised an eyebrow. But after six months of rhetoric from President Bashir, everyone suddenly has an opinion on the issue. Rejecting the UN has become the central plank of Sudan's foreign and domestic policy. With the stakes so high any climbdown from Sudan could threaten the continued survival of President Bashir and his government. |

Tens of thousands of people, probably many more, died. Over two

million Darfurians were driven from their homes. In the face of such

misery, the world's largest humanitarian operation was hastily assembled

to provide food and water.

Tens of thousands of people, probably many more, died. Over two

million Darfurians were driven from their homes. In the face of such

misery, the world's largest humanitarian operation was hastily assembled

to provide food and water.  As the fighting escalates May's Darfur Peace Agreement, or DPA, now

looks much more like a military alliance than a comprehensive peace

agreement. The gamble taken by the international community to back a

deal signed by just one rebel faction (Minnawi's SLA) has back-fired

spectacularly.

As the fighting escalates May's Darfur Peace Agreement, or DPA, now

looks much more like a military alliance than a comprehensive peace

agreement. The gamble taken by the international community to back a

deal signed by just one rebel faction (Minnawi's SLA) has back-fired

spectacularly.