|

Dayan Jayatilleka's latest book :

An interrogative piece on 'Fidelismo'

The following is the English translation of a review essay by Prof.

Remy Herrera which has appeared under the headline "Morale de la

revolution" in the December 2008 edition of Afrique-Asie, the reputed

French magazine. "Re-defining the terms of a moral ideal of rebel

resistance: How to master revolutionary violence? questions the Sri

Lankan academic Dayan Jayatilleka in his latest book. It is by

practising a strict code of ethics, the way the 'Maximum Leader' did,

proving that the limits imposed on legitimate violence help avoid terror

and extreme violence and that those limits help gain popular support.

|

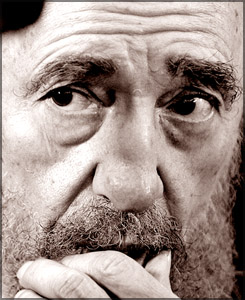

Fidel Castro |

For nearly a decade, Latin America has become a place of resurgence

of the people's struggle for national sovereignty, respect for cultural

diversity, social progress and democracy. This renewed vigour in the

Latin American people's resistance, and the strong and permanent

ideological reference that the Cuban revolution and its historic leader

Fidel Castro (whom Hugo Chavez Frias, the President of the Bolivarian

Republic of Venezuela, calls his "political father") constitutes in the

heart of that popular movement, compel us to interrogate the nature,

value and the modernity of 'Fidelismo'.

That is precisely what Dayan Jayatilleka, a steadfast progressist, a

lecturer at the Department of Political Science and Public Policy at the

University of Colombo and representative of Sri Lanka to the Human

Rights Council at the UN in Geneva, has undertaken to do in a profound

and important work titled Fidel's Ethics of Violence, published in

English, by Pluto Press, London.

Cuba's adherence to Communism since 1959 and the survival of the

Cuban Revolution beyond the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early

1990s can be understood only in the long-term perspective, through a

complex analysis of the conditions under which they fused with Cuba's

struggles for national liberation and social emancipation.

The role played by Fidel Castro - from the commander of a guerrilla

war to the victorious Head of State of the Tricontinental - in the

consolidation of the Cuban people's resistance and in maintaining their

unity in the face of the dangers they encountered, should be evaluated

for what the Cuban people were, and still are: this is absolutely vital.

It is to the fundamental basis of this reality that Dayan Jayatilleka

chooses to draw the attention of the reader; although many Western

leftist administrations might still be hampered by great confusion and

have not yet found, due to the incessant bombardment of the media

feedback, the ways of rebuilding their internationalism and an active

solidarity with the peoples of the South; although great leaders of the

Third World may not yet be truly recognised - even by many Marxists - as

having contributed to the advancement of the history of thought in

political philosophy, in general - and in Marxism, in particular;

although Fidel himself, disgusted by the personality cult and political

pragmatism, has not systematized his vision of the world in a completed,

written doctrinal work.

According to the author, Fidel Castro's major contribution is the

moral and ethical dimension which characterizes his thought and action.

The sources of his ethics are deeply rooted in the history of the "Cubanism"

itself, in its very special mix of idealism and realism, in the

successful combination of the humanist heritage of Jose Marti (the

initiator and hero of the war for independence who died in the battle in

1895) and Marxism-Leninism, and in the unique way of balancing the

exercise of power and the imperative for virtue.

This is one of the fundamental reasons for which the Cuban Revolution

not only was not entombed with the USSR (how many times should it be

reminded that Cuba is not a residue of the Soviet Union, lost in the

Caribbean?), but also did not, hitherto, resort to terror to prevail.

And this is certainly not strange because up to now, of all the great

revolutions, it is the one that took place in Cuba that gave its leaders

- first of all, to the first among them - the longest, widest and most

solid support of its people.

At the heart of the topic resides of course the issue of

revolutionary violence and its containment - that is to say, the use of

violence in a "fair" or "correct" manner - when an entire nation rises

up clamouring for its liberation. Because, if we accept that (these

obvious facts have now become taboos) the violence of the oppressed is

not of the same nature as that of the oppressor - a Palestinian child

who grabs hold of a stone against an Israeli soldier who holds him at

gun point - and that people can legitimately opt for armed struggle to

resist oppression - French resistance under Nazi occupation, the

Algerian "rebels" during the fight for Independence, the Vietnamese

fighting against the U.S. aggression, were they terrorists? - an

inevitable disquieting concern arises: what are the limits that are to

be imposed on this legitimate violence?

Dayan Jayatilleka shows how Fidel Castro was capable of defining

these impassable limits through an inflexible code of ethics, and how he

put it to practise in Cuba even during the movement of people's

rebellion. And this code of honour, these universal values which were

practised even in the guerrilla war, who else than Ernesto Che Guevara -

the heroic guerrilla, the "moral giant" as Fidel called him- could be

more pure and popular to have been able to symbolize them? One day in

1958, after a battle against the army of the dictator Batista in the

mountains of Sierra Maestra, a guerrilla asked Fidel "What shall we do

with the prisoners?" Fidel's answer was: "Treat them humanely.

Do not ever insult them. And remember, for us, the life of an unarmed

human being must always remain sacred."

It's this ethic that nurtured the Cuban Revolution since its very

beginning, on the island as well as beyond its borders, in the

deployment of its military internationalism in solidarity with the

struggles of other nations, against colonialism, imperialism and

apartheid.

And again, it is this ethic that made him constantly safeguard the

lives of the non-combatant civilians, refuse the execution of the

prisoners of war and reject torture.

After all, everyone knows this (even John McCain, who nevertheless

claimed to have been "tortured" by Cubans in Vietnam ... although there

were no Cuban fighters in Vietnam!): If torture is used on Cuban soil,

it is in the Guantanamo base, and nowhere else, that is to say, it is in

this piece of land that the United States holds since the military

occupation of the island in 1898 and which it refuses to give back to

the Cuban people for over a century.

Dayan Jayatilleka does not brush aside any problem (neither of

philosophical nature nor of practical nature), makes no effort to

differentiate (from other revolutionary experiences in the South,

Ethiopia, Cambodia, Afghanistan, Iran, Sri Lanka ...), does not forget

any of the painful issues (for example, the Ochoa case).

Through his nuanced, courageous and 'against the current' thinking,

he offers all progressives the opportunity, both to set up the terms of

a moral ideal of rebel resistance and to rebuild a concrete alternative

which fits challenges of modernity.

And to the most radical among them, this book might help them even to

rethink the unthinkable under such trying conditions at the beginning of

this twenty-first century: another world, which is better and ...

socialist.

Remy Herrera, Professor in Development Economics at the Universit‚ de

Paris 1, France, is a researcher at the CNRS, the National Centre for

Scientific Research, and the Director of the Social Forum collection at

Edition L'Harmattan, Paris. A collaborator of Prof. Samir Amin, he is a

member of the World Forum of the Alternatives - FMA, Dakar. |