Earthhope

Trends and perspectives

Policies for irrigation development:

by J. Alwis

The policy initiatives for the program to develop irrigation

facilities in the dry zone were first taken by the colonial government

during the first quarter of this century when Sri Lanka experienced the

travails of an impoverished economy. The rural peasantry was the worst

affected by the economic despondency which gripped the country during

this period. Official documents of that time bear witness to famines and

near famine conditions in the Dry Zone, abject rural poverty,

deprivation and starvation among rural peasantry. The incipient

development of a policy which concerned itself with the welfare of the

rural peasantry was given shape towards the end of the quarter and was

crystallized into recommendations in the Land Commission report of 1927.

These

recommendations were subsequently translated into an action programme

through the Land Development Ordinance in 1935. These

recommendations were subsequently translated into an action programme

through the Land Development Ordinance in 1935.

Irrigation construction for land redistribution

1. The programme which dealt with land and water resources

development and through which rural welfare policies were committed to

action acquired the form of a land redistribution programme for which

even special agencies such as the Land Commissioner's Department and the

Land Development Department were set up. The bias towards land

redistribution was prompted in a large measure by the difficulties that

had to be encountered in attracting people to settle down in dry zone

parts of the country.

On the one hand the dry zone conditions offered a harsh and an

inhospitable environment infested with Malaria. On the other the unequal

competition between paddy cultivation and the plantation crops persisted

with paddy yields in Sri Lanka being the lowest in Asia. The policy

makers therefore asserted that the colonization of the dry zone through

which the redistribution of population would be effected was the only

way out and that it will soon become 'not a matter of choice but a grim

necessity'. So the challenge before the government was to formulate and

implement a programme which would make the transfer of the wet zone

rural population to the dry zone as attractive and feasible as possible.

Considering these circumstances under which the programmes had to be

implemented the accent on social welfare policies could not have been

easily avoided.

1. As Malaria was responding to DDT spraying, prospects for

increasing the pace of the programme became brighter. In 1948 when Sri

Lanka became an independent nation, the social and political objectives

of the programme appear to have been far more important than its

corresponding economic potential and it was well on its way to become

the cornerstone of government policy to promote peasant welfare.

1. In retrospect, the emphasis on land redistribution for the 'colonisation

of the dry zone' resulted in certain negative features of the programme

being left unaltered. Firstly the integration between the irrigation

sector and the agriculture sector left much to be desired and even today

it has proved to be a major constraint. Given the state of technological

development achieved by the Department of Agriculture in paddy and other

domestic crops in forties and early fifties, an immediate breakthrough

in producing a food surplus through irrigation systems did not appear to

be all that feasible, although the best conditions for irrigated farming

existed in dry zone conditions.

1. Secondly the peasant welfare policies in the manner they were

dovetailed to the resettlement programme conveyed an impression which

was totally incompatible with the costs effectiveness of the programmes

implemented. By and large, irrigation and settlement programme was

understood as a social service programme to relieve people of their

immediate distress.

1. Thirdly the design of the physical system did not take into

account the need to incorporate measures to assure effective water

distribution and the proper water management to guarantee equitable

distribution at field level. Physical structures for the control and

regulation of water flows were conspicuously absent in major irrigation

systems designed during this period. The distributary and field canals

were of irregular lengths and in certain cases the length of each field

channels was over one mile. Obviously the need to manage water was not a

primary consideration in the design philosophies adopted in planning

these schemes.

1. Fourthly the design of irrigation system was mainly intended to

provide supplementary irrigation during Maha and not necessarily aimed

at a Yala cultivation in the manner that these facilities are being

utilized today. So the discharge capacity of the canal system was

limited. Evidently the provision of supplementary irrigation facilities

during Maha did not place a high premium either on the control

capacities of the system or on the capacity of farmers to obtain and

share water equitably. In expanding the scale and intensity of operation

to meet the new demands for extensive cultivation, inadequate canal

capacities seem to have acted as a major constraint in system

operations.

1. On reflecting upon these situations, comments offered here could

be easily said today than they were acted upon before. From an

engineering perspective, maximum consideration was given to ensure

safety of the reservoir. Then it was also necessary to bring as much

cultivable land as possible into the command areas so that the largest

number of farm families could be settled. The irrigation system was

therefore stretched on all sides like a membrane to accommodate the

demand for more lands and much of them originated with political

interventions.

When canal and other reservations were also annexed to the system,

its operation proved to be even more difficult, and management problems

were further compounded resulting from additional lands being considered

as recipients of legal water entitlements.

Maximising agricultural production

1. Until sixties, the programme for the development of irrigation and

settlement schemes was financed entirely by local funds. The pattern of

allocating investment resources in favour of irrigation and settlement

development however began to attract criticisms in the second half of

fifties. This situation was further heightened by the attractive

economic benefits in the plantation sector. The wisdom of making further

allocations for the establishment of colonisation schemes was then

challenged and appeared in several of the government planning and policy

documents. For instance, the Agriculture Plan issued by the Ministry of

Agriculture and Food in 1958 commented that "the cost of current

policies of land development, irrigation and colonisation are extremely

high and that the annual production in the average dry zone colony

represents only about 16% of the total capital outlay". Prof. Kaldor, a

visiting economist advised the government that "large scale schemes for

the development of food production by means of irrigation are found to

be very wasteful in comparison with large scale schemes for the

development of plantation agriculture". Outside these references,

several other view points asserted that in terms of earning scarce

foreign exchange, employment and return on investment in industrial and

plantation sectors were far more attractive than investments in land

developments.

1. Alongside these changes in the thinking, the more important

development however took place in the agriculture sector with the

introduction of the new technology of high yielding varieties by the so

called Green Revolution. The new variety of H-4 had been already bred

towards the end of fifties and rice breeders appeared to have closely

identified factors concerning the environmental conditions, new

techniques of breeding and plant types related to the spread of high

yielding varieties even as early as mid-sixties. Varietal trials

conducted under different agro-ecological conditions confirmed that

strategies for rice breeding should adopt perceptive changes more

suitable to local conditions and that it should be even tailored to

satisfy the weaknesses arising out of low input technology to which most

farmers resort to in discounting risks in paddy farming.

1. The decade of sixties was a watershed in the development of

irrigated agriculture in Sri Lanka. On reaching sixties, the restoration

of the more important large reservoir have been completed or taken in

hand. The construction of new reservoirs in new sites was becoming

costly.

Down-stream development was proving to be even more costlier. Lack of

local funds to support a continuation of the programme for irrigation

and settlement development required a revision of the implementation

strategies which favoured maximizing production in irrigation systems.

The technological development in the agriculture sector facilitated this

change in emphasis as high complementarity existed between irrigation

facilities and the high yielding varieties.

A change in the direction and emphasis from peasant welfare

programmes to an effort at maximizing production output required

organizational and institutional changes. Already the Paddy Lands Act of

1958 ushered a new era by introducing tenancy reforms. Amendments were

introduced in the first half of sixties to the Irrigation Ordinance and

Paddy Lands Act to incorporate new thinking on combining institutional

development with the process developed for irrigated agriculture. Even

more importantly the prohibition on cultivating other crops in paddy

fields was removed giving new impetus to the cultivation of subsidiary

crops. Enhanced Agricultural Credit, providing legal status to

Guaranteed Price Scheme and extension of the same scheme to other crops

and promotion of Agricultural Insurance for paddy are some of the other

important institutional innovations introduced during sixties through a

package of institutional reforms.

1. The new emphasis on maximising production as generated by the

social, political, economic and technological environment that prevailed

during sixties also resulted in precipitating plural approaches promoted

through national level participation and also through individual

initiatives by officials themselves. In 1965, the new Government Agent

of Anuradhapura, late Mr. Mahinda Silva who in his previous posting

functioned as Director of Agriculture, experimented with two important

innovative approaches in his District. In the programme which he

initiated for certain minor irrigation systems in Kahatagasdigiliya

area, an attempt was made to co-ordinate services provided by the line

departments with a view to eliminate certain production constraints

which the farmer had to encounter at the field level and provide

extension support in maximising resource utilization. This programme

eventually aimed at optimizing the services provided by field level

official without increasing their numerical strength. In the second

programme, the strategy worked out for the minor system was developed to

prepare an Agriculture Implementation Programme for the district with

planning targets being fixed in close collaboration with grass-root

organisations.

1. Perhaps the more important events that took place in the period

after mid-sixties were further enhanced by the arrival of a mission in

Sri Lanka under the auspices of the FAO/IBRD Co-operative Programme to

review the status of the irrigation development programme in Sri Lanka

as envisioned by the Government of that time. The mission was popularly

referred to as the Pepersak Mission, named after the mission leader who

was an agronomist.

More specifically the arrival of the Mission was in response to a

request by the government to obtain foreign funds to finance the

irrigation programme. The Mission was expected to review the strategies

to optimize resource utilization and make recommendations on

institutional, organizational, managerial and technical measures

required to ensure successful execution and operation in existing and

future projects.

1. The report of the Mission submitted in 1967 asserted that "the

objective of increasing productivity (and income) of farmers, of capital

and of land must take primacy over the objective of settling the maximum

number of families without regard to whether these families can

eventually earn enough to pay taxes rather than having to rely

indefinitely on direct and hidden subsidies". The mission

recommendations included irrigation rehabilitation instead of expanding

the irrigated extent through new construction of irrigation projects,

and undertaking lift irrigation, drainage and reclamation programmes.

It also recommended measures to intensify agricultural production by

formulating package programmes to increase the flow of agricultural

inputs, water control to prevent inefficient and wasteful practices and

initiate crop diversification to enhance farmer incomes..

1. Amongst the recommendation made by the Mission, highest attention

was however given by the government to a programme to intensify the

production output by launching the Special Projects Programme (SPP) of

1967 which covered approximately 80,000 acres in 24 major systems. This

programme coincided with the spread of the Green Revolution technology

which was seen as a solution to the teething problems of food deficits

in the Asian region. The worsening food crisis and the depleting foreign

exchange situation added more impetus to the goals enunciated by the SPP

and the Prime Minister himself actively participated in reviewing and

monitoring its progress.

1. Within few years of initiating the SPP a rapid upsurge in the

paddy yields was recorded in major systems. But before long the

programme started showing signs of exhaustion and was unable to sustain

its initial momentum.

1. From the present state of knowledge, the following are two

important shortcomings seen in the implementation of the SPP.

a) The importance given to maximize the yield potential was far in

excess of the attention given to the need to sustain achievements which

could have been attained through active involvement and participation of

farmers in the development process.

b) Since adequate attention was not paid to the availability of a

reliable and predictable supply of water, the need for institution

building to develop a process for water management was overlooked.

Emphasis was however given to strengthen the hand of officials in the

management of the programme.

1. Indeed the SPP was an important milestone in the culmination of

thinking which attempted look beyond the mere confines of a settlement

programme with peasant welfare as its principal objective. It also

signalled the first step in the large scale transition of subsistence

agriculture to commercial farming in major schemes.

The integrated approach of this programme to increase production

featured new institutional devices and approaches to co-ordinate

agriculture development work in Districts. As a matter of act it was

also intended as a dress rehearsal to determine the development

strategies most suitable for the Mahaweli Development Programme which

was in the planning stage.

1. Following are some of the key lessons learnt from the SPP which

were to influence subsequent development in the sector.

a) The need for a holistic approach combining economic and social

development goals in project objectives leading to total development;

b) Acknowledgement of the need for a better co-ordinated effort at

the project level by formulating an action programme and obtaining

commitment from line agencies for implementation;

c) Recognizing inter-disciplinary team work in irrigated agriculture;

d) Combining lowlands and highlands for crop diversification;

e) Demonstrating the feasibility of cultivating subsidiary field

crops in the dry zone on commercial scale with high profitability;

f) Recognize the need for judicious planning to phase out excessive

official involvement and facilitate the sharing of management

responsibilities with farmers;

g) Acceptance of the need to introduce new management structures,

incentives and organizational patterns to meet new demands.

To be continued

Give back to life

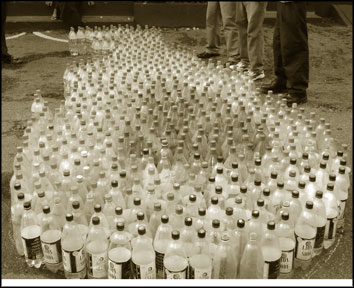

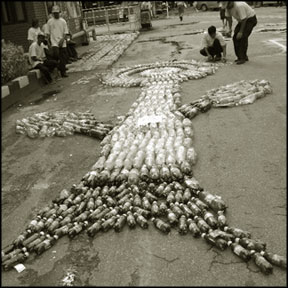

Commemorating the World Environment day on June, 5 Coca-Cola

Beverages Sri Lanka Limited completed three successful PET collection

drives among the employees of Coca-Cola, the residents and schools of

the Biyagama area, and the Manik Farm IDP Centre in Vavuniya.

The

main project marking this endeavor was conducted in collaboration with

residents of the Biyagama area. All the used PET bottles collected

during the programme went to the plant in Biyagama. Each employee was

rewarded depending on the number of bottles contributed. A total of

almost 4000 bottles were collected on PET collection day at the plant. The

main project marking this endeavor was conducted in collaboration with

residents of the Biyagama area. All the used PET bottles collected

during the programme went to the plant in Biyagama. Each employee was

rewarded depending on the number of bottles contributed. A total of

almost 4000 bottles were collected on PET collection day at the plant.

Residence of Biyagama also collected PET bottles, which were

collected by staffers. The project was a success, with a total of

approximately 913 kg (20,000 bottles) of PET being collected within a

timeframe of 3 hours.

The number of bottles exceeded the anticipated number as there was an

overwhelming contribution from the residents of the area following the

effective awareness campaign conducted prior to the date of collection.

Another segment of the Environment Day programme was collecting PET

from the Biyagama Primary School and the Biyagama Central School. This

initiative too was successful with both schools contributing over 850

PET bottles.

The students were rewarded for their conscious efforts towards

protecting the environment. The highest number of bottles from an

individual student was from Saubhagya Neerodhi of the Biyagama Central

School, who brought 70 bottles while the highest number of bottles from

a class was from the 5 A Class of the Biyagama Primary School, which was

207 bottles.

The

collection of PET bottles from the IDP centres in Vavuniya was the third

initiative by Coca-Cola to commemorate World Environment Day. This

project witnessed the collection of 450 kg of PET bottles from the Manik

Farm IDP Centre in Vavuniya. The bottles were collected and brought to

the Coca-Cola plant in Biyagama on the 5th of June in a symbolic gesture

in commemoration of the World Environment Day. The

collection of PET bottles from the IDP centres in Vavuniya was the third

initiative by Coca-Cola to commemorate World Environment Day. This

project witnessed the collection of 450 kg of PET bottles from the Manik

Farm IDP Centre in Vavuniya. The bottles were collected and brought to

the Coca-Cola plant in Biyagama on the 5th of June in a symbolic gesture

in commemoration of the World Environment Day.

“Our initiative on World Environment Day has heightened the awareness

among our employees as well as the residents of the area regarding PET

recycling.

We hope to sustain this momentum and continue our recycling efforts

among the employees as well as the residents of the area” said Patrick

Pech, Country Manager, Coca-Cola Beverages Sri Lanka Limited.

“The ‘Give Back Life’ project has come a long way since its inception

in July 2008” said Manish Chaturvedi, Country Manager, Sri Lanka and

Maldives, Coca-Cola Far-East Limited. An overwhelming collection of 1.3

tons of PET waste was made during this endeavor.

Near

extinct? Near

extinct?

Family - Arecaceae

Scientific Name - Calamus pachystemonus Thw.

Sinhalese Name - Kukulu Wel

Status - Critically Endangered, Endemic

Calamus pachystemonus belongs to Arecaceae family (palm family) that

includes more than thirty species and ten species are recorded only from

Sri Lanka. Genus Calamus consists of ten species among them C.

pachystemonus restricted to few lowland rain forests in Kalutara and

Galle. It is a most endangered palm species in Sri Lanka.

It is slender small, clustering climber (30-50 cm in height). The

stem of the climber is thin, about 1 cm in diameter with leaf sheath.

Leaves are small, pinnate (30-50 cm long, 20 cm wide) and dark green in

colour. Flowers are arranged as clusters. Identification features are,

pinnately arranged leaflets.

According to the 2007 Red List of Threatened Fauna and Flora of Sri

Lanka C. pachystemonus is a critically endangered species. This species

is under threat of extinction due to depletion of forests, especially

tea cultivation near forest areas, logging, habitat destruction, etc...

Pic source: Dassanayake & Clayton 2000

Reference

1. Dassanayake, M.D. and Clayton, W.D. (eds.) (2000) A revised

handbook to the flora of Ceylon. Oxford IBH, New Delhi.

3. De Zoysa, N. & Vivekanandan (1994) Rattans of Sri Lanka Forest

department, Sri Lanka.

2. IUCN Sri Lanka and the Ministry of Environment and Natural

Resources (2007). The 2007 Red List of Threatened Fauna and Flora of Sri

Lanka, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

By Dilup Chandranimal

IUCN (The International Union for Nature Conservation of Nature)

Sri Lanka-Country Office. |