Looking before, after and abroad

Modern Sri Lankan Literature:

by Dr. Wilfrid JAYASURIYA

|

|

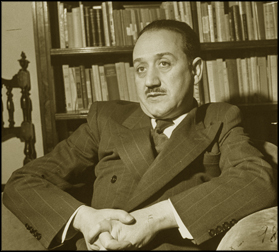

Ignazio Silone, the Italian author who

won the Nobel prize for literature |

The story of the return to a once beloved place or person is a common

theme, perhaps an archetypal theme, focusing on the validity of memory

and the concepts of space and time in our lives. One could abstract

oneself from the specifics of time, place and memory and think of these

stories as having a commonality about existence. Ignazio Silone, the

Italian Nobel prize winning author, who was very popular in Ceylon in

the early post independence decades, was well known for his story,

“Return To Fontamara”. Fonatmara is a village located in Southern Italy,

which was a poverty stricken agricultural area, in the post war period.

The protagonist in the story returns to his village and listens to a

story about a man who was sent to gaol for a long period, for a crime

which involved the death of the man’s girl friend.

Later, when the man came back from gaol, it appeared he had gone to

gaol to cover up for his girl friend’s reputation, though he was himself

innocent.

The theme of return is therefore tied up with the theme of

revelation.

The theme of return is developed in Chitra Fernando’s “Bird of

Paradise,” a short story about a Sri Lankan migrant . This theme was

developed as a full length novel but this story seems to encapsulate a

recurring theme in the return story: the loss of a loved one when the

returnee was absent from the scene. The death of the loved one enables

the writer to develop the theme of nostalgia for the past, as it existed

when the returnee lived there, and contrast it with the present, while

also developing a contrast between her feelings for her new “home” in

Australia and for her old “home” in Ceylon, as it is seen here and now.

Remembering how she had fled from Negombo, back to Sydney almost

twenty one years ago, she thought of Dominic Perera the immediate cause

of her departure...What would her life have been had she married Dominic

Perera? But it was Ray Maxwell she had married...She had been looking

for something: a being unconstrained by custom and tradition, a splendid

freedom. Yet she’s settled so easily for comfortable ordinariness, not

really different from her mother or Aunt Mary, from Srini. Her thoughts

drifted...The smell of jasmine was in her nostrils. She was sitting in a

latticed verandah with potted ferns lining the steps. Was it Aunty Mary

scolding Jose or simply a chatter of crows? And then out of the purple

blaze of the bougainvillea flew out the shining bird. “Its you-you I

always wanted,” she called out jumping up from her chair. But the bird

had vanished. She only saw the endless distances of the sky as she stood

alone in the verandah of the silent house. (Kaleidoscope 69)

In this last paragraph, from the story, Chitra Fernando displays her

truly gifted mastery of the narrative mode. Within the forty year period

from the 1950s to the 1990s, the consciousness of Sri Lankans, which was

limited in aspiration to the immediate environment of their newly

independent country had expanded to possibilities in other continents

and other roles, and literature reflected these changes.

Isankya Kodituwakku, in her collection “The Banana Tree Crisis”

includes a story titled “The House In Jaffna” which deals with the theme

of the longing for return to the homeland, this time from England to

Jaffna instead of from Australia to Negombo. In her story about Jaffna,

a Tamil family from London comes back with great optimism to Jaffna,

when the peace agreement or the ceasefire of 2000 is confirmed. They

find their house destroyed and occupied and their former servants and

neighbours are extremely unfriendly. They don’t see any future for

themselves and get back to London.

The impact of the story consists of the disparity between the

internal vision that Nadarajah has of his native land and family house

and childhood environment and the reality of the present. It is a simple

contrast between London and Jaffna but it is real. Its quality is what

Aristotle describes in one of his books as the “taste of the real.”

James Joyce, when theorising about literature in a passage from “The

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man”, touches on this quality as a

marker of high achievement, the sense of being out there, outside the

mind of the narrator, there in its own right. In Joyce’s translation of

that quality it is called the “whatness.” That is a quality, which Carl

Muller’s fiction does not share, marked as it is by the power of the

imaginative fantasy, communicating, as it does, the wonderfully shaded

vision of the creator himself. When Isankya talks of Nadarajah we know

that she is not talking of herself. She is talking of the “whatness” of

Jaffna. One has to read the whole story to appreciate the reality. I

shall quote the beginning and the end:

The House in Jaffna

When Nadarajah rode the train each evening from Waterloo Station to

his home in Teddington, he almost always had a bright peaceful look on

his face.

Most people who saw him probably thought he was a man with a happy

family life, who rode the train in anticipation of home. Although the

assumption about his family life was correct, they were wrong when they

thought it was a look of anticipation. Rather it was a look of memory.

Because the home he was thinking of was not his present home forty five

miles out of London but an old, white walled house in Jaffna. (from The

Banana Tree Crisis)

The reader is brought into a discussion, with the writer, about

correct and incorrect assumptions and so the story becomes a

participative event the reader has with the writer. The maintenance of

this tone of confidentiality is the special characteristic of Isankya’s

narrative. The various shocking and unlikely events that happen, when

the family moves to Jaffna, include the rude rebelliousness of the

family’s former servant’s son, who touts an AK47. But this scene is

given a wonderful twist when the old servant, Siva, turns up and drags

his LTTE son away by the neck, as he would have done when Nadarajah was

a child, in the good old days, when he was the little master of the

house. So a bizarre social situation is created and Nadarajah realizes

that everything is far from being on all fours with his dream of home. The reader is brought into a discussion, with the writer, about

correct and incorrect assumptions and so the story becomes a

participative event the reader has with the writer. The maintenance of

this tone of confidentiality is the special characteristic of Isankya’s

narrative. The various shocking and unlikely events that happen, when

the family moves to Jaffna, include the rude rebelliousness of the

family’s former servant’s son, who touts an AK47. But this scene is

given a wonderful twist when the old servant, Siva, turns up and drags

his LTTE son away by the neck, as he would have done when Nadarajah was

a child, in the good old days, when he was the little master of the

house. So a bizarre social situation is created and Nadarajah realizes

that everything is far from being on all fours with his dream of home.

Siva [the old retainer] walked out of the compound and Nadarajah

stared after the old servant for a few minutes before he turned to face

his mother, standing a few feet from him. When she caught his eye she

came over and patted his shoulder absently. “The fish that has a narrow

escape from the heron fears all that is white,” she said, her eyes

already drifting away in another direction.

The tension and confusion created in the mind of the returnees is

aptly conveyed in this pithy analogy. Who is the heron and who the fish?

But the incompatibility of the two is the essence of the Jaffna

situation where Nadarajah still remains “Mr Nadarajah.”

In other stories such as “Michelle de Kretser’s “The Hamilton Case”,

the writer who has left the colonized territory and resettled in another

country reverts back to her country of birth and sees it with a

distancing and satirical vision, implicitly measuring it against the

preferred new cultural home which she has adopted. Though there is a

certain nostalgia in the detailed memories of the past in another

country, where interesting things happened because you belonged to an

elite group whose activities were significant, yet those very activities

are now seen as both exciting and irrelevant to the writer’s own future.

One of the most interesting characters, if not the most interesting, is

the character of a Sinhalese landowner who moves around in the elite

Burgher circles but is at the same time the true symbol of the darkness,

which the European enlightenment had hoped to dispel, once and for all,

from the country and society which they had colonized. I often wondered

whether this Sinhalese landowner in the Burgher social network is a

figure for D. S. Senanayake, (also known as “Jungle John”)who appears to

have been a figure of fun, among sophisticated and westernized Ceylonese

groups. Diyonisius Sumanasekera in De Lanerolle’s play “Fifty Fifty”

appears to be a figure for “D.S.” too.

In Chandani Lokuge’s novel, “If The Moon Smiled”, a Sri Lankan

Sinhala woman, who has emigrated to Australia still feels a longing for

home expressed as a need for self fulfilment and an escape from

loneliness.

“As a young woman in Sri Lanka, Manthri marvels at the promise of

life and yearns for a future of fulfilled dreams. Years on, she finds

herself in a loveless marriage, in a foreign land, and estranged from

her two Australian children.

Torn between an idyllic past to which she cannot return and a present

that breaks her heart, she never loses touch with those dreams, nor

abandons her passionate enchantment with life.

“I go down to the river, unheeding my mother’s disapproval. I dip

into the lazily flowing water. Here, at least, nothing has changed. The

bath-cloth balloons around my body and I press it down. I loosen my hair

and let it spread where it will. I open my hands upwards on the water’s

surface, languidly remembering. All, all that is familiar. The promise.

The promise of life.”

However, when she revisits Lanka, in her search for a fulfilling

experience, that she has not found in Australia, she is set upon by

young men on the beach in the south of Sri Lanka, and that experience of

near rape, is a countervailing lesson depleting her desire for the past.

Thus in the works of Chitra Fernando, Michelle Kretser, Ishankya

Kodituwakku and Chandani Lokuge a variety of experiences pervade the

narrative of arrival and departure, the genre of literature which looks

before and after and also abroad.

We look before and after

And pine for what is not

Our sincerest laughter

With some pain is fraught

Our sweetest songs are those which sing of saddest thought

|