French Renaissance literature

The current series of columns on French literary movements has, until

now, primarily focused on Medieval literature. This study has included a

review of Arthurian legends and fables, farces and morality tales. Among

the texts examined are 'Roman de la Rose' (and related poetry), and 'La

Chatelaine de Vergy'. These, among other tales of French courtly love,

were important precursors to a number of French Renaissance texts, which

are the subject of this column. The current series of columns on French literary movements has, until

now, primarily focused on Medieval literature. This study has included a

review of Arthurian legends and fables, farces and morality tales. Among

the texts examined are 'Roman de la Rose' (and related poetry), and 'La

Chatelaine de Vergy'. These, among other tales of French courtly love,

were important precursors to a number of French Renaissance texts, which

are the subject of this column.

The late 15th and early 16th century saw the birth of the Renaissance

in France. The civil and religious strife of the later 16th century was

reflected clearly in the period. Under the stable and prosperous Bourbon

monarchy, Paris became the glittering cultural centre of Western

civilisation. Literature during the French Renaissance passed through

four fairly distinct phases. Each new generation of writers developed

its own set of ideas and styles. Many important works of this period are

difficult to place within specific genres, or literary forms. Writers

often created new forms by combining elements of various older

traditions.

The first generation included Clément Marot, Margaret of Navarre, and

François Rabelais. These writers borrowed the forms and customs of

medieval literature, but used them to express anti-medieval ideas and

beliefs. Marot's earliest poems are allegories in the tradition of the

Roman de la Rose (Romance of the Rose), a long French poem about courtly

love, which was studied in the 20th March - 'Fabliaux, Farces and

Morality Tales'.

Margaret of Navarre also wrote several plays similar in style and

form to medieval farces, but with a new emphasis on religious themes.

She also copied the short, humorous, and often obscene stories of the

Middle Ages in her Cent Nouvelles (One Hundred Stories). However, this

collection of tales also reflects the influence of Boccaccio's

Decameron, leading some scholars to call it the Heptameron. The work

represents the finest body of short stories from the French Renaissance.

|

|

Descartes |

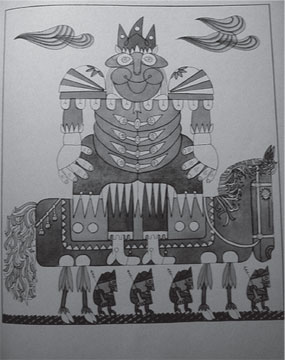

Rabelais is the possibly the most groundbreaking writer of this

generation. In his long narrative Pantagruel, he borrowed from the

tradition of the medieval epic, but at the same time moved far beyond

it. The result was an entirely new form of heroic fiction more in tune

with the author's humanist views. Combining humour with impressive

scholarship, Rabelais recounted the adventures of giant heroes who are

saved from a life of ignorance and brutality by a humanist education.

They eventually save the world from the flawed political, religious, and

scholarly ideas of the Middle Ages. In later sections, Rabelais broke

away from the epic tradition completely to explore the limits of human

knowledge and the idea of the abuse of power.

The Pléiade

In the mid-1500s, a group of poets known as the Pléiade (a name based

on Greek mythology) set out to make a clean break from the literary

traditions of the Middle Ages. They systematically rejected all forms

and customs of the French literary tradition and sought to return to

ancient Greek and Latin models. Their aim was to sweep away all traces

of the Middle Ages, which they saw as a period of ignorance, and raise

the French language and culture to the heights reached by ancient Greece

and Rome.

Joachim du Bellay expressed this ambitious goal in his Defense and

Illustration of the French Language. He saw this work as the most

important turning point in the history of French literature. Along with

the Defense, du Bellay published a collection of odes modeled on those

of Horace. Pierre de Ronsard, a close associate of du Bellay, published

a longer collection of poems that re-created the structure and style of

Pindar's odes. Étienne Jodelle, another member of the Pléiade, attempted

to revive the forms of classical drama with his tragedy Cleopatra in

Prison and his comedy Eugène.

The next generation of French writers found classical forms and

styles too limiting. They also saw the glory of the ancient world as an

unimportant idea in a country increasingly torn by religious wars. On

August 24, 1572, religious tensions in France burst out in a wave of

killings known as the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre. This tragedy

inspired a new generation of writers to create violent, intense, and

passionate works with a focus on the inner life of the mind. They began

combining different types of literary forms, creating works that do not

fall into familiar categories. Their works led in the Baroque period in

literature.

Michel de Montaigne was perhaps the most important writer of this

period. Although he admired the classical poems of du Bellay and

Ronsard, he chose to write in a manner that was decidedly anti-classical

in form, style, and purpose. His Essays are essentially exercises in

which he tests his own judgment on a variety of topics. Through these

tests, Montaigne revealed his own personality and his new vision of

reality as uncertain and ever changing. Another great writer of this

period was the poet Agrippa d'Aubigné. A student of classical

literature, he kept some of the lyric forms created by the Pléiade, but

he broke away from their style and filled his work with images of war,

martyrdom, and destruction.

The end of the Renaissance in France

In the first decades of the 1600s, French writers continued the

literary experiments of the previous generation, but in a different way.

They returned to familiar literary forms and created new ones to express

both the passions of the soul and the workings of the mind. Theatre

became the most popular form of literature during this period.

Playwrights mixed genres to produce new types of drama, such as

tragicomedy and the pastoral play.

The so-called libertine poets revived the poetic tradition with their

spirited verses about the pleasures of the tavern and the brothel, the

wretchedness of poverty, and the sources of poetic inspiration. They

used forms first invented by the Pléiade but also drew on the works of

earlier writers. When this generation of poets died out, lyric poetry

effectively ended in France for more than a century.

In the area of prose, autobiographies became popular. Perhaps the

greatest of these was Discourse on Method by the noted scientist and

philosopher René Descartes. The book traced the author's intellectual

development and described his method of inquiry in a style that

reflected the Essays of Montaigne. Montaigne's work also inspired author

Charles Sorel, who drew on a great variety of literary forms to create

the first authentic novel in French. In addition to Montaigne, his

sources included French nouvelles (short stories), libertine poetry, and

the Spanish picaresque novel (a story about the adventures of a rogue or

rascal).

In spite of the fact that the general view is that the French

Renaissance began in the 15th century, some scholars claim that the

French Renaissance really began in the late 1400s, when the Italian

writers Petrarch and Giovanni Boccaccio first began to have an influence

on French literature. In either case, France's Renaissance began much

later than Italy's, and as a result, it was shaped by very different

forces.

Humanism and Religious Wars

While the Italian Renaissance focused on reviving classical culture,

the French Renaissance began mainly as a religious movement. France was

a major center of theology and French thinkers had a stronger interest

in recovering the texts of early Christianity than in the pagan

literature of ancient Greece and Rome. Trends and ideas from northern

Europe played a major role in the French Renaissance.

The Dutch humanist Desiderius Erasmus, who tried to return the church

to its early Christian roots, inspired the first wave of French

Renaissance writers. Clément Marot translated several pieces by Erasmus

and composed allegorical poems about the rebirth of pure Christianity.

In addition, he translated nearly 50 psalms into French verse that

ordinary people could sing as they worked. Erasmus's literary techniques

also had a great influence on François Rabelais, who produced works of

biting satire attacking the Christianity of his day.

Religious reformer Martin Luther also had a strong influence on

French writers, especially Margaret of Navarre. Her poems, plays, and

other works combined elements of Luther's theology with the mysticism of

the late Middle Ages. Many of her pieces portrayed humble souls who were

saved by the mystery of God's grace.

|

|

Pantagruel by Rabelais |

Through Margaret, Luther's views influenced the circle of young

writers she supported and promoted, which included the young John

Calvin. The Protestant Reformation in France set off a bloody civil war

between Protestants and Catholics. Many writers took sides in the

religious conflict. The Catholic author Pierre de Ronsard attacked

Protestant beliefs and practices, while the Protestant Henri Estienne

mocked what he saw as the superstitions of the Catholic Church.

Classical literature and philosophy

By the time the French turned to the classics for inspiration, they

had access to a great number of ancient Greek and Roman works that had

not been available to earlier writers. New advances in printing made

these literary works easier to find and read than ever before. French

writers also had an advantage in trying to understand these works.

Italian scholars had made great advances in the study of Greek in the

previous 200 years, and many Greek scholars had moved to western Europe

in the 1400s, bringing their learning and libraries with them. By the

time of the French Renaissance, writers could study the Greek language

or read Greek works in Latin translation.

These advances in classical studies had a decided influence on French

writers. Rabelais, for example, knew enough Greek to lecture and write

commentaries on the works of the ancient physicians Galen and

Hippocrates. Poets of the mid-1500s, such as Ronsard and Joachim du

Bellay, studied the works of ancient Greek and Roman poets, such as

Virgil, Horace, Pindar, and Homer. Enthusiasm for these ancient writers

inspired them to compose their own poetry in French. Many writers also

admired the works of classical philosophers, such as Plato, Lucretius,

and Seneca.

Italian literature

French writers studied Italian literature to find new ways of writing

in the vernacular. French art and literary works of the late 1400s

already show distinct Italian influences. In the 1530s, a major phase of

Italian influence began in the city of Lyon, in southern France.

A large number of Italians lived in Lyon, and many Italian books were

published there. One of them, Petrarch's Canzoniere (Book of Songs),

became the model for a new kind of French poetry. Clément Marot

translated several poems from the Canzoniere and composed what may have

been the first original sonnet in French. Maurice Scève published the

first French "canzoniere" in direct imitation of Petrarch. The Italian

sonnet replaced all French lyric forms as the standard for love poetry.

French poets composed collections of sonnets devoted to a single lady,

just as Petrarch had done.

French writers also imitated other Italian works, such as the

Decameron by Giovanni Boccaccio and The Book of the Courtier by

Baldassare Castiglione. Orlando Furioso (Mad Roland), a long poem by

Ludovico Ariosto, inspired French writers in a less direct way. It

provided a stock of well-known characters, situations, and speeches that

appeared in all forms of literature.

Italian influences on French literature remained strong until the

late 1500s, when writers turned against the Italian style-largely

because of anti-Roman Catholic religious feelings.

It is beyond the scope of this one column to study each of the most

important works associated with French Renaissance Literature. As it is

a large topic, individual works will be reviewed in future columns.

|