|

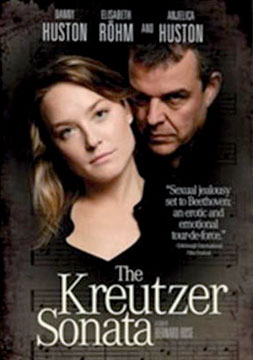

Leo Tolstoy’s KREUTZER SONATA-:

The resonance of paranoia

[Part one]

By Dr. Siri GALHENAGE

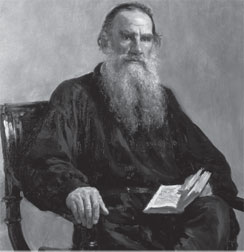

Last November, many events took place around the world to celebrate

the life and work of Leo Tolstoy, also known as Count Lev Nikolayevich

Tolstoy. Writing about this important event, the Moscow correspondent of

Daily Telegraph Andrew Osborn said that “Russia now is being accused of

abandoning its literary past in case of the outstanding Russian writer

Leo Tolstoy, because Russia ignores the 100-year anniversary of his

death.” This is a clear indication how literary works of even literary

giants are treated and interpreted over the years.

|

|

Part one |

Could universal judgements be passed on the work of writers such as

Tolstoy and Pasternak is a key question which merits our attention.

However, interpretations, and analysis of Tolstoy’s work, giving new

insights into the work of this literary genius will take place from

different cities of the world by different critics. The following is an

exclusive analysis of Leo Tolstoy's much discussed novella--Kreutzer

Sonata-- by Dr Siri Galhenage who has worked in UK and Australia as a

Consultant Psychiatrist. Could universal judgements be passed on the work of writers such as

Tolstoy and Pasternak is a key question which merits our attention.

However, interpretations, and analysis of Tolstoy’s work, giving new

insights into the work of this literary genius will take place from

different cities of the world by different critics. The following is an

exclusive analysis of Leo Tolstoy's much discussed novella--Kreutzer

Sonata-- by Dr Siri Galhenage who has worked in UK and Australia as a

Consultant Psychiatrist.

Reverence for Leo Tolstoy as a literary icon stems from his in-depth

understanding of the human condition expressed in novelistic fiction.

One such piece of literary art is his celebrated novella, the Kreutzer

Sonata [1889], narrated in direct and lucid style but laden with much

psychological material to ponder. Here, Tolstoy creates the character of

POZDNYSHEV, the protagonist, breathes life into him with a belief

system, and sends him off first on a mental mission which culminates in

the heinous act of killing his wife; and then on a journey of

self-revelation that provides a window to his psyche and the societal

attitudes of his era.

On a long train journey spanning several days Pozdnyshev reveals his

story to a fellow traveller who was ready to lend an ear to him, after

other passengers had either got down at their destinations or moved onto

other carriages. Pozdnyshev’s revelations were triggered by an earlier

discussion amongst fellow passengers about love, marriage, sensuality

and morality, which appeared to have had a cathartic effect for him by

unloading his own ‘baggage’.

Why did Pozdnyshev kill his wife? A beautiful woman with ‘curly hair

and a shapely figure’ whom he fell in love with after ‘an outing on a

boat on a moonlit night’, and whom he thought was ‘the acme of moral

perfection’, ‘worthy of being his wife’

In my reading of the novella, the answer to that question lies in

Pozdnyshev’s self-revelations. The purpose of this analysis is to track

and provide a review on the motivational path taken by him and to

reflect upon the psychological processes that may have driven him to

commit an act of murder.

Love, marriage, sensuality and morality

The initial conversation in the railway compartment was initiated by

a lawyer who makes the observation that divorce has become a common

topic of public discussion in Europe and that marital separations are

occurring more often even in Russia.

An old man, a tradesman, who was earlier bragging about his own

sexual misdemeanours, is drawn into the conversation arguing that

education was the cause of marital discord and that the female partner

of a marriage should take a subordinate role and her activities curbed

in order to preserve the marriage. “Don’t trust your horse in the field,

or your wife in the house!” he says, making exit on reaching his

destination.

Dismissing the old man’s views about women and marriage as

‘barbarous’, the woman companion of the lawyer joins in saying that

“marriage without love is not marriage” and that ‘love sanctifies

marriage’.

“Marriage without love lacks the element that makes it morally

binding”, adds the lawyer, corroborating her views. “Love is an

exclusive preference for one above everybody else”, she said, in

response to a request by Pozdnyshev for a definition of love.

She suggests that love should be based on “identity of ideals and

spiritual affinity” and not on ‘physical love’. Pozdnyshev, with a

cynical view of love and marriage, expresses his doubts as to the

existence of love other than sensual, saying that marriage is “nothing

but copulation” and that it is maintained through “deception or

coercion”: polygamous in behaviour but pretending to be monogamous. In

an animated expression of his views, Pozdnyshev asserts that, “husband

and wife begin to hate each other after a month [of marriage] ...wish to

part but still continue to live together, it leads to that horrible hell

which makes people take to drink, shoot themselves, or kill or poison

themselves or one another.”

After identifying himself as the man who reached that ‘critical

episode’ in married life and killed his wife [perhaps it was a well

publicised case at the time] Pozdnyshev begins confiding in the only

remaining [anonymous] passenger in the compartment who in turn relays

the story to the reader in the third person narrative style..

**************

Self-revelation

Pozdnyshev is a landowner, a graduate of the university and a marshal

of the gentry. He grew up in a society that expected men, in their

formative years, to engage in sexual activity without making any moral

commitment to women. Such misconduct was considered legitimate, “good

for health”, “something to be proud of”, often sanctioned by parents and

even by the State that regulated brothels to make them safe for boys.

Pozdnyshev has indulged in debauchery since the age of 16, but suffered

a deep sense of remorse for having “lost his innocence” thinking that he

has sullied his ability for intimacy with women. He could detect a

debauchee by the way the latter eyed a woman.

|

|

Leo Tolstoy |

“I weltered in a mire of debauchery and at the same time was on the

lookout for a girl pure enough to be worthy of me. I rejected many, just

because they were not pure enough to suit me, but at last I found one

whom I considered worthy”. In selecting a wife, he says, “one is

attracted to beauty and charm, ignoring the true-self of the individual,

and live together in marriage denying one’s own past profligacy.”

Continuing on the theme of denial and pretence Pozdnyshev explains

that men do not know [or do not wish to know] but women know very well,

that so called “poetic love” depends not on moral qualities but on

outward appearance. Women know very well, he says, that what a man needs

is not “high sentiments” or “elevated conversation” but her body, and

that the women acting accordingly have converted the upper classes into

a “shameless brothel”. Much of the energy gained through sumptuous

meals, in his opinion, was spent on sensuality.

Pozdnyshev believes that despite the humiliation suffered at the

hands of men by being considered the objects of sensuality, and legal

rights and privileges designed to favour men, women adopt a dominant

role. Women subdue and enslave men by acting on men’s sensuality.

Deprived of equal rights, women demand and maintain the luxuries of

life.

In fact, Pozdnyshev did not marry for money or connections, and was

resolved to be monogamous, and was proud of it, unlike most of his

acquaintances who continued to practice polygamy despite being married.

During his engagement, Pozdnyshev was soon to realise that love,

which according to him was a spiritual communion [not sensual], did not

find expression in words. For many, he argues, going to church was only

a special condition for gaining possession of a certain woman. “An

innocent girl is sold to a profligate and the sale is accompanied by

certain formalities”.

He describes his honeymoon experience as vile: “horrid, shameful and

dull”. His view is that “sex-passion” in people hindered the attainment

of union of souls through love – the purpose of human existence, and

argued a case for striving towards ‘continence’. When confronted by his

interlocutor that such a practice would lead to the demise of the human

race, his response was that according to the teachings of the church and

that of science, the end of the world is inevitable.

Honeymoon

The honeymoon had premonitions of an acrimonious relationship between

Pozdnyshev and his wife. Once amorousness was exhausted by the

satisfaction of physical needs, they were left confronting each other in

their true relationship. Frequent quarrels with the exchange of cruel

words were followed by periods of embraces, hugs and tears.

Love, in reality, he believes, is abominable, although in theory it

was something ‘ideal and exalted’. Human beings are created like

animals, he thought, so that physical love is followed by pregnancy and

then by suckling.

But unlike animals that follow the rules of nature, women demean

themselves by yielding to the sexual desires of men, even when they are

pregnant or are nursing. The only escape for women, he explains, is to

develop hysteria or nervous disorders as seen in upper social classes or

“be possessed by the devil” as seen amongst peasantry.

Despite raising the educational standard of women and giving them

equal rights, they continue to be regarded as “instruments of

enjoyment”. The women on their part, he believes, tended to perpetuate

that position, and not consider it degrading as it gives them the

opportunity to ‘bewitch’ men even when married. The only time such a

situation goes into temporary abeyance is when a woman has children or

nurses them herself.

Pozdnyshev was aggrieved by the doctor’s recommendation that his wife

refrain from nursing her first child due to her apparent ill health.

“And those doctors who cynically undressed her and felt her all over –

for which I had to thank them and pay them money – those dear doctors

considered that she must not nurse the child; and that first time she

was deprived of the only means which might have kept her from coquetry”.

By his own admission, rearing of children, for him and wife, is not a

joy but a torment. Concerns over children’s health and shifting rules

about bringing up and educating children, unsettled them. Children were

often the object of their discord and were drawn into taking sides. Yet

children were needed as justification for staying together in marriage.

The couple could not understand each other and “never tried to bring

any dispute to a conclusion”. Acrimonious words were exchanged regarding

matters of no importance. “Thus we lived in a perpetual fog not seeing

the condition we were in”.

They lived in denial of their misery by being occupied in business

affairs, household duties and social engagements.

Pozdnyshev admits that during the whole of his married life, he never

ceased to be tormented by jealousy. When his wife was free from

pregnancy and suckling, the “feminine coquetry that lay dormant within

her manifested with particular force” coinciding with an exacerbation of

his jealousy. She paid more and more attention to her appearance and

revived her interest in the piano.

He feared that in the same way that she “abandoned her moral

obligations as a mother” by not nursing her first child, at the

recommendation of the doctors, she may abandon him.

The “terrible abyss” between the couple continued alternating with

“intense animal passion”. “Her every word was venomous”, he says, “my

whole being is seized with fury”. She ran away from home at times

arousing fears that she may harm herself.

There were times that he dreamt of getting rid of his wife and

uniting with another woman. At other times he has contemplated suicide

and was aware that his wife repeatedly tried to poison herself.

(To be continued)

For feedback-

[email protected]

|