|

A voyage of discovery :

Exploring the nexus between childhood and adulthood

By Ranga CHANDRARATHNE

Although

The Cat’s Table offers readers with rich textured prose and almost

photographic memoirs directly connected with the lives and evolution of

characters of its passengers, the line between the fiction and faction

is rather blurred. It seems that the author has exploited the literary

licence to the maximum in ‘colouring’ the texture with incidents from

the past as well as grotesque descriptions of the locations and times

such as St.Thomas’ in Mount Lavinia. According to the author, the

incidents and descriptions of the locations are purely fictional and do

not, therefore, reflect the milieu against which the story is set. Although

The Cat’s Table offers readers with rich textured prose and almost

photographic memoirs directly connected with the lives and evolution of

characters of its passengers, the line between the fiction and faction

is rather blurred. It seems that the author has exploited the literary

licence to the maximum in ‘colouring’ the texture with incidents from

the past as well as grotesque descriptions of the locations and times

such as St.Thomas’ in Mount Lavinia. According to the author, the

incidents and descriptions of the locations are purely fictional and do

not, therefore, reflect the milieu against which the story is set.

The Cat’s Table, the latest novel by Michael Ondaatje, recounts,

principally, the passage of an 11-year-old boy named Michael from

childhood to adulthood in the space of three-week’s journey from Colombo

to England via the Suez Canal in the cruise liner Oronsay.

Interestingly, the name and the time of the narrator Michael slightly

coincide with the author’s journey from Colombo to England. The Cat’s

table is the lowest rank of dining arrangements for contradictory and

dissimilar boys who seek school admission in England; “Mynah”, (the

narrator Michael), tough boy Cassius and weak and philosophical Ramadhin,

provide the readers with an important vantage point. From that vantage

point, the narrator could survey the entire liner across the class

distinctions and diverse dramatic personae, who people it during its

voyage.

The novel commences with the narrator, a -11-year-old boy named

Michael boarding the ship berthed at Colombo harbour for the first and

the last time in his life,: “ He was eleven years old that night when,

green as he could be about the world, he climbed aboard the first and

only ship of his life.

He went up to the gangplank, watching only the path of his

feet-nothing ahead of him existed –and continued till he faced the dark

harbour and sea. There were outlines of other ships futher out,

beginning to turn on lights.

He stood alone, smelling everything, and then came back through the

noise and the crow to the side that faced land. A yellow glow over the

city. Already it felt there was a wall between him and what took place

there. …”

It

is the entry of the narrator into an entirely new world, a sailing

castle on the vast sea which can easily be compared to the world with

its diverse social strata. However, from the very commencement of the

novel, it is clear that the very purpose of the novelist is not to do a

class analysis as in the Titanic although Oronsay is a luxury cruise

ship. The purported intent of the author seems to portray the evolution

of the narrator’s character. The maturity of the 11-year-old trio

achieve through the interaction with the adult’s world and some daring

acts they willingly engage during the course of the journey. From

initial encounter with the adults, the trio seems to be infected with

the curiosity around the strange goings –on in the liner. It

is the entry of the narrator into an entirely new world, a sailing

castle on the vast sea which can easily be compared to the world with

its diverse social strata. However, from the very commencement of the

novel, it is clear that the very purpose of the novelist is not to do a

class analysis as in the Titanic although Oronsay is a luxury cruise

ship. The purported intent of the author seems to portray the evolution

of the narrator’s character. The maturity of the 11-year-old trio

achieve through the interaction with the adult’s world and some daring

acts they willingly engage during the course of the journey. From

initial encounter with the adults, the trio seems to be infected with

the curiosity around the strange goings –on in the liner.

Assortments of characters

The ship is peopled by an assortments of characters "Emily, Mynah’s

cousin (Michael) on whom Michael depends at times of distress, Flavia

Prins, a first –class traveller whose husband know’s Michael’s uncle and

who has promised to keep an eye on him. Later she proves to be a gossip

monger.

The diverse characters have their own hobbies; Miss Lasqueti keeps a

cage of pigeon. Asuntha is isolated and in a green dress concealing a

terrible secret. Sri Lankan millionaire Sir Hector de Silva is in a

luxurious suit dying from a curse. The teacher Mr.Fonseka is armed with

books and burns a bit of hemp rope to recall the past, Mr.Danial has a

huge garden of medicinal as well as poisonous herbs and Max Mazappa or

Sunny Meadows is a jazz musician who befriends with Miss Lasqueti but

leaves the ship at Port Said. However, the most intriguing character is

the lonely prisoner who walks in the midnight on the deck under heavy

guard.

The primary purpose of the assortments of diverse characters is to

provide the readers with a rich texture with many treads and patterns.

At a different level, they serve the author to go back and forth in time

on the one hand to recall his memories of Ceylon and to bring out

diverse aspects of life on the other.

Prisoner

|

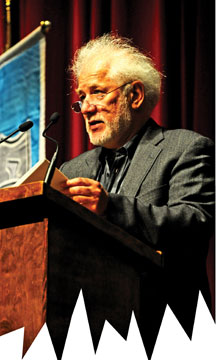

Michael Ondaatje |

The very appearance of the prisoner is intriguing and the prisoner,

among other elements such as Sir Hector de Silva’s curse, provides the

novel with an aura of mystery.

“It was before midnight. The deck shone because of a cloudless moon.

He appeared with the guards, one chained to him, one walking behind him

with a baton. We did not know what his crime was. We assumed it could

only have been a murder. The concept of anything more intricate, such as

crime of passion or a political betrayal, did not exist in us then. He

looked powerful, self-contained, and he was barefoot”

Nostalgia

The major thread of the novel is nostalgia. It is not only the

recollections and snap shots of personal history of the narrator but

also of different characters and the time they live in. On one instance,

the narrator reveals in a kind of soliloquy, his personal history and

how his parent’s divorce and about his formative years in Ceylon:

“When my parents abandoned their marriage, it was never really

admitted or explained but it was not hidden. If anything, it was present

as a mis-step, nor a car crash. So how much the curse of my parent’s

divorce fell upon me I am not sure. I do not recall the weight of it.

The boy goes out the door in the morning and will continue to be busy in

the evolving map of his world. But it was a precarious youth…what was I

in those days? I recall no outside imprint, therefore, no perception of

myself. If I had to invent one photograph of myself from childhood, it

would be of a barefoot boy in shorts and a cotton shirt, with a couple

of friends from the village, running along the mildewed wall that

separated the house and garden in Boralesgamuwa from the traffic on the

High Level Road…”

One of the potent objects of nostalgia is ‘a hemp rope’. The readers,

first, find the ‘hemp rope’ in the narrator’s recollection of his

childhood in Boralesgamuwa and later ‘ burning hemp rope’ has been aptly

used to bring about loads of recollections about the bygone life in

Ceylon when the narrator goes in search of the smell coming from a cabin

in Oronsay only to find Mr. Fonseka, the teacher.

“I always joined Narayan for this dawn meal after he awakened the

generator. Breakfast with him on High Level Road was not to be missed,

even though it meant I would have to consume another, more official

breakfast with the family an hour or two later. But it was almost heroic

to walk with Narayan in the dissolving dark, greeting the waking

merchants, watching him bend to light his beedi on a piece of hemp rope

by the cigarette stall…And then, one day, I smelled burning hemp on the

ship. For a moment I stood still, then moved towards a staircase where

it was stronger, hesitated about whether to go down or up, then climbed

the stairs. The smell was coming from a corridor on D level. I stopped

where it seemed strongest, got on my knees, and sniffed at the inch of

crack under the metal door…”

Emily

It is this burning of hemp that the narrator leads to discover Mr.

Fonseka, the teacher. The narrator meeting with Emily years after the

journey and now Emily leads a secluded life in a cottage in Canada.

“And so I continued to watch Emily, this person who had been for a

while some kind of despot of beauty in my youth. Though I knew her also

as quiet and cautious, even if she sometimes gave off the air of an

adventurer. But the stories of her married life, in their various

postings, and the affairs of the heart that had occurred, seemed a

familiar version of my cousin, as she had been on the Oronsay. Had she

become the adult she was because of what had happened on that journey? I

didn’t know. I would never know how much it had altered her. I simply

thought it over to myself at that moment in Emily’s spare cottage on one

of the Gulf Islands, where she appeared to be living alone, seeming to

hide herself away…Then, when her marriage finally ended, Emily decided

for some sad reason on a sort of exile on this quiet island on the West

coast of Canada…

It seemed a not quite real life compared with what she and I probably

imagined when we were young. I still had memories of us on bicycles

being slammed by a monsoon rain, or Emily sitting cross-legged on a bed

as she talked about that school in India, and her lean brown arms waving

to me during one of our dances. I thought of those moments as I walked

beside her now.”

Here nostalgia works not only as a conduit between the past childhood

memories and the present but also as filling the gaps in a long

narrative that took place in the post journey era. These snap shots of

nostalgia and soliloquies of the narrator lend authenticity in an

organic manner to the narrative and would make the journey

metaphorically longer than it had actually happened. At deeper level, it

makes much needed connectivity of the journey with the life journey of

Oronsay’s passengers.

The novel ends with a memorable passage describing the narrator

Michael meeting up with his mother in England.

“ … A few hours earlier I had unrolled and put on my first pair of

long trousers. I had put on socks that crowded my shoes. So I was

walking awkwardly as we all descended the wide ramp down to the quay. I

was trying to find who my mother was. There no longer remained any sure

memory of what she looked like. I had one photograph, but that was at

the bottom of my small suitcase…It must have been a hopeful or terrible

moment, full of possibilities.

How would he behave towards her? A courteous but private boy, or some

eager for affection. I see myself best, I suppose, through her eyes and

through her needs as she searched the crowd, as I did, for something

neither of us knew we were looking for, as if the other were as

accidental as a number plucked from a pail who would then be an intimate

partner for the next decade, even for the rest of our lives…”

Journey

The novel narrates a journey from childhood to adulthood as well as a

passage from homeland to another country. The sense of passing the

demarcation between the East and the West was strongly evoked when the

ship passes through the Suez Canal. They hang on the bow rail, "where we

could witness the fragmentary tableaux below us – a merchant with his

stall of food, engineers talking by a bonfire, the unloading of refuse,

all of them, all of this, we knew we would never see again. So we came

to understand that small and important thing, that our lives could be

large with interesting strangers who would pass us without any personal

involvement."

The memoirs of all what had taken place on board the Oronsay were

carried on in the memories of its passengers, how they shaped their

lives as never before.

Wafer thin line between fiction and faction

Although The Cat’s Table offers readers with rich textured prose and

almost photographic memoirs which directly connected with the lives and

evolution of characters of its passengers, the line between the fiction

and faction is rather blurred. As if to cast off any doubt about its

fiction, at the end of the novel the author states in no uncertain terms

that “Although the novel sometimes uses the colouring and locations of

memoir and autobiography, The Cat’s Table is fictional-from the captain

and crew and all its passengers on the boat down to the narrator…”

What is intriguing and ambiguous is the term ‘colouring’ and it is

not quite clear whether the locations such as Boralesgamuwa and High

Level Road are too purely fictional as well as the legend of Sir Hector

de Silva which may or may not have any association with a similar yarn.

Sir Hector de Silva’s legend is described as: “It had happened this way.

One morning Hector de Silva had been breakfasting on his balcony with

friends... At that moment, a venerable battaramulle- or holy

priest-walked past the house. Seeing the monk, Sir Hector punned off the

title by saying ‘Ah, there goes a muttaraballa’. Muttara means

‘urinating’, and balla means ‘dog’. Therefore, ‘There goes a urinating

dog’.

Remark

It was a quick-witted but inappropriate remark. Having overheard the

insult, the monk paused, pointed to Sir Hector, and said, ‘I’ll send you

a muttaraballa…’ ” . Cassius’s descriptions about St.Thomas’ in Mount

Lavinia are such an account which is highly doubtful and unconvincing.

The description is about the inferior quality toilets at the school.

“… He was especially celebrated after he managed to lock ‘Bamboo Stick’

Barnabus, our boarding-house master, in the junior school toilet for

several hours to protest the revolting lavatories at the school. (You

squatted over a hole of hell and washed yourself afterwards with water

from a rusty tin that once held Tate & Lyle golden syrup. ‘Out of the

strong came forth sweetness’, I would always remember.). ”

Although the description of locking up the boarding master may help

highlight the adventurous Cassius’s character, one would doubt whether

it is absolutely necessary to go into such gory details of toilet

facilities at the school.

It is doubtful whether the author is subscribing to the notion ‘East

is dirty and the West is exotic’. Throughout the novel in such grotesque

descriptions line between the fiction and faction is blurred and the

author can, always, argue that such descriptions have also been used for

‘colouring’ the narrative. After all, it is the literary licence of the

author. |