|

A pedagogic survey :

Changing facets of English in Sri Lanka

By Ranga CHANDRARATHNE

In the conclusion, Siromi Fernando states,

“There is inconsistency in the following rules in all the dialects.

There has also been sociological change in the description of the users

of the dialects. Apart from this, features of one dialect have begun to

occur in other dialects as well. Hence since there are some confused

patterns in the dialects at present, although the general

characteristics of each dialect can be described, it is difficult to

define clear rules. ” In the conclusion, Siromi Fernando states,

“There is inconsistency in the following rules in all the dialects.

There has also been sociological change in the description of the users

of the dialects. Apart from this, features of one dialect have begun to

occur in other dialects as well. Hence since there are some confused

patterns in the dialects at present, although the general

characteristics of each dialect can be described, it is difficult to

define clear rules. ”

Siromi Fernando’s contribution is noteworthy

given the fact that she has quite candidly explained the actual position

with regard to the existence of diverse varieties of Sri Lankan Standard

English and that a clear distinction can hardly be made among those

varieties.

The entire discourse on Sri Lankan English

or the homespun varieties of English raises pertinent issues such as for

whom these varieties of English developed, and how the distinct purpose

such varieties would serve particularly in the domain of international

relations and commerce. It is also highly polemical whether these

varieties of English are acceptable to the population at large and the

power wielders of the society. What is obvious is that such varieties of

English may contribute to the growing body of world Englishes and would

be of importance from pedagogic perspectives and perhaps, to maintain

English as a potent class indicator as stated by Thiru Kandiah.

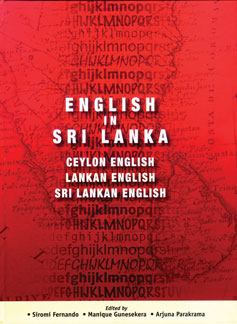

The academic publication English in Sri Lanka,: Ceylon English,

Lankan English, Sri Lankan English is one of the seminal publications to

emerge from Sri Lankan academia on the evolution of English in Sri Lanka

and its myriads usages in diverse domains such as governance, education

and in day-to-day life.

The book, consisting of 21 papers, is edited by Prof. Siromi

Fernando, Prof. Manique Gunasekera and Prof. Arjuna Parakrama, and is a

publication by SLELTA (Sri Lanka English Language Teachers’

Association).

The primary motive of the book as stated in the introduction is to

‘provide documentary evidence of the existence of systemic and

rule-governed varieties of English in Sri Lanka, as well as to record

that the recognition and study of these varieties has a distinguished

disciplinary study. ” .

The publication offers, among other things, rich reference materials

for teachers, academics and the readers to identify and study diverse

varieties in Sri Lanka and their functionalities in different domains.

The book is divided into five sections under the titles, 1. History

and Development of English in Sri Lanka, 2. English: Education &

Literature, 3. Sri Lankan English Phonology, Morphology & Vocabulary, 4.

Language Choices, Functions & Policies and 5. Standards & Dialects of

Sri Lankan English.

Evolution of English in Sri Lanka

Prof. Siromi Fernando |

Prof. Manique Gunasekera |

Prof. Arjuna Parakrama |

In the essay entitled ‘Ceylon English’, H. A. Passe observes a

home-grown variety of English in Sri Lanka which he describes as ‘Ceylon

English’. This is, perhaps, one of the earliest instances of the

recognition of a variety of English other than British English which was

bequeathed to Sri Lanka during the British occupation of the island for

over 200 years.

Passe states, “ There has grown up in Ceylon a form of English with a

distinct flavour of its own in regard to pronunciation and intonation,

and in the case of most people, idiom, grammar, and vocabulary as well.

The explanation of this form of English would include the

investigation (i) of social and educational background of those who

taught English to the Ceylonese; (ii) of the extent to which the sounds

of Sinhalese and Tamil have influenced the pronunciation of Ceylon

English; (iii) of the prevalence of ‘translation errors’, i.e idiom and

grammatical usages imported from Sinhalese and Tamil into Ceylonese

English; (iv) of the extent to which words from the indigenous

languages, and from Indian languages and Portuguese and Dutch, are

commonly used in this form of English. ”

However, Passe observes there is ‘a negligible minority who for

special reason can speak and write Standard English’.

He observes different users of English , who use ‘a very mixed and

impure form of English’. The variety of English that he recommends is

the one ‘used by English-educated Ceylonese’. “ But there is a kind of

English used by English-educated Ceylonese, chiefly those in whose

families English has been used as the only or the first language for

several generations (including Burghers, Sinhalese and Tamils), in which

the sounds vary but slightly from those of Standard English –no more

than a northern-born educated Englishman’s might, in which the melodies

or tunes are not markedly different from those of Standard English, and

from which local idiom and grammar are practically absent.

This form of English is thus unobjectionable and can be taught,

provided there is a carefully selection and training of teachers in

modern methods of teaching English as a foreign language.”

It is interesting to note some of the translation errors that Passe

has pointed out in his paper may be still relevant to the contemporary

users of English in Sri Lanka.

“Cookwoman (Kussi amma) , In Ceylon, ‘cook’ is usually refers to a

male (Kokiya), and a female cook is designated cookwoman or cookie.

At this moment the cookwoman returned from the boutique. Columnist

In England, ‘cook’ is used for a person of either sex, but more often

refers to a woman, a male cook being a ‘chef’.

Junction (Handiya): cross roads

Boutiques, markets and small shops are usually to be found at a

‘junction’ or a meeting place of roads, in Ceylon. It is a centre of

life and activity to which people go to meet friends, to gossip, to buy

and sell. Hence one often hears, ‘You can get this at the junction’, ‘ I

am going to the junction for a few minutes ( mama handiyata tikak

gohilla enava)…

Man (Miniha)

In C.E. man is used colloquially in a sense similar to English ‘ my

dear fellow’, ‘I can tell you ’, ‘old fellow’. With the C. E. use maybe

compared with Eng. ‘man’ as an impatient or lively vocative’ ‘Nonsense,

man!’, ‘ Hurry up, man!’, ‘ Man alive’. ”

In as early as 1979, Doric de Souza has clearly identified the

‘Targets and Standards’ that Sri Lankans should adaopt considering

English from a utilitarian point of view. He concludes his paper

entitled ‘Targets and Standards’ making a pertinent point; “I ignore,

also, though I am wrong in doing so, the fact that English is a status

symbol in Sri Lanka and that it serves as a social barrier. This is

unfortunate but true.

..Here we must distinguish between the standards of written English

(of a utilitarian character as defined above) and spoken English.

Standards of English in utilitarian written English are uniform and

universal- I ignore the small variants in orthography, grammar, syntax

and vocabulary that occur with American English, because generally

speaking, a formal letter or a work of academic exposition can be read

without difficulty by people in anywhere in the English speaking world.

We should enforce the standards of written English without permitting

any local variants, which do not in fact occur in the fields I have

referred to.

Spoken English is another matter. Our English speaking elite in Sri

Lanka have evolved their own pronunciation which differs on one side

from British or American and from local “sub-standard” English. ”

English as a tool of power and potent class indicator

In his paper entitled “ Kaduva” : Power and the English Language

Weapon in Sri Lanka”, Prof. Thiru Kandiah, among other things, describes

the dominant attitude towards English entertained particularly by

Sinhalese and Tamils with a low degree of proficiency in English. For

them, English is not merely a language but a potent class weapon and

class indicator. At a time English speaking natives were branded as

‘English speaking classes.

Kandiah observes that although English is thought to be a second

language, for the “English speaking class it is the first language and

the power that it accompanied allowed them to fill the top positions in

the administration which has been a virtual heirloom for them, “… As

would be expected, therefore, whatever concessions may have been made to

the native languages in the country at large, the position of English

was jealously guarded at these higher levels.

No doubt, there was an immediate practical reason for this: the

bilingual elite who manned those higher level positions had always

carried on their activities in English, and they now found that they

could not perform at all effectively at these levels but in that

language.

The main factor was, however, power. It was the English language that

had raised these people to their position of power, and it was the

English language that, by separating them as a social class from the

rest of the people of the country, ensured that they would remain in

these positions to the exclusion of the latter.

The point is that since English functioned as something very

different from a utilitarian secondary language at these levels, as in

fact, a badge of privilege, the ordinary people, to whom English could

at best be nothing more than just a utilitarian second language but

something of a social accomplishment too had access to these levels.

This ensured, incidentally, that it would be they who would provide,

in a self-perpetuating manner, the personnel to fill the positions at

these levels.”

Privilege of language

Arjuna Parakrama’s paper entitled ‘Some thoughts on the language of

Privilege & the Privilege of Language’ represents the current discourse

on standards and de-hegemonising standards of English in Sri Lankan

academia.

Citing the largely failed year 11 English text book English Every Day

and some letters and answer scripts by students, Parakrama seeks to

propose his thesis that teachers or standard bearers should reverse

their privileged role.

He states; “ Here we come full cycle, then, to the point at which our

aim- as teachers of the standard bearers of the torch etc.- is to

destabilize, broaden this standard towards the creation of a situation

where the Rules and Tools are, in fact and not fiction.

Theirs (our students, the subaltern majority, the marginal, third

worlder, woman, worker). To learn (or rather unlearn) to read persistent

errors as resistance with our without demonstrable intention, and to

respect its radical difference. Ours was the privilege, as linguists,

teachers, codifiers, standard bearers and so on to confer the privilege

of language on these other Calibans so that their profit on’t was to

curse us in it.

Diverse domains

Let the roles be revered: Let us learn their (version of) language to

earn the right to the privilege of ours. Otherwise, we are simply acting

out the words of Wittgenstein: a crack is showing in the system, and

we’re trying to stuff it with straw, but to quieten our consciousness

that we’re using only the best straw. ”

One of the principal domains in which English is extensively used is

in the sphere of Higher Education and at universities. In the paper

entitled ‘English in the University’, E.F.C. Ludowyk explains in no

uncertain terms that the standard of English, particularly, of English

graduates produced by the system of Universities is ‘For those who wish

to read English standard can be no other than that demanded of the

undergraduate in English in any English or European University’.

However, Ludowyk admits that the standards of English can vary or as

he terms, ‘drop in the standards inevitable’. He observes, “In the

meantime with a drop in standards inevitable- standards in the level of

English attained by the candidates at the Preliminary examination- the

University may have to undertake courses of a general kind in the

reading and understanding of English for the benefit of all those who

wish to follow university courses.

For those who wish to read English the standard can be no other than

that demanded of the undergraduate in English in any English or European

University.

For him too, as for the rest, there will be need to study how words

behave and how our attitudes are influenced by their behaviour. Not in

the hope of twenty or thirty years ago when semantics was the new

“science” which was going to save the world, but with the chastened

feeling that if the way the world has been going in the last twenty five

years has taught university faculties anything, it should have made

clear that there is much to be said for the kind of education which

encourages a skeptical distrust of mass appeal in the name of race,

religion or even humanity.”

In a paper entitled “Influence of English on Sinhalese Literature”,

Martin Wickramasinghe, explores the overarching influence of English

literature and language on Sinhalese literature in general and on the

evolution of Sinhalese novel in particular.

Quoting Ananda Coomaraswamy, Wickramasinghe points out those

Sinhalese writers should derive inspiration from world literature

readily available in English and in turn enriching contemporary

Sinhalese literature rather than becoming mere admirers of Western

literature.

“The danger is not that the future Sinhalese writers will fail,

because of their narrow nationalism, to assimilate Western culture

through the medium of English; but that they will become lavish admirers

and imitators of Western literature instead of trying to seek

inspiration from every source and developing their own independent

creative genius.

This requires not nationalism but critical ability or insight to

probe the genuine core of Eastern and Western cultures. Beneath seeming

differences there is a core of unity in all cultures. Unless we develop

our critical insight to understand this core we are in danger of

becoming either narrow nationalists or superficial cosmopolitans.

….Says Ananda Coomaraswamy, “We must beware; for there are two

possible, and very different, contingencies that can follow from

cultural contacts of East and West.

Language without metaphor

One can , like Jawaharlal Nehru, and his own words, ‘become a queer

mixture of East and West, out of place everywhere, at home nowhere,’ or

being still oneself ‘in place’ anywhere, and ‘at home’ everywhere..in

the profoundest sense, a citizen of the world.”

One of the interesting and though provoking paper is ‘A language

without metaphor: A note on the English Language in Ceylon’ by Godfrey

Gunatilleke. Gunatilleke points out, among other things, that English in

Ceylon has limitations when it comes to describing authentic native

experiences or cannot be used as an all purpose language due to a lack

of metaphor to describe Sri Lankan experiences. He points out that in

Sri Lanka; English is a language without metaphor.

“It would be difficult to imagine vernaculars in Ceylon becoming as

lifeless and as thin as the English spoken by our English-educated

middle-class. In fact, the Sinhalese spoken by our middle-class is with

few exceptions very little different from its English. In the few

Sinhalese dramas produced by certain members of the Ceylon University

Staff, such as Kapuwa Kapothi, or Pabhavati, where an intelligent

response was expected, it is significant that the middle-class

situations chosen were naturally comic ones…the difficulty would arise

only if one attempts to use a contemporary colloquial idiom….The best we

can hope for is the ready commerce and interaction of the English of the

English-educated community and the vernacular, through an intelligent

bilingual community; that is , a group which could think in English and

the vernacular alike and bring into the natural stream of the vernacular

the attitudes and ways of thinking of the English-educated till the

terms of reference form a part of normal discourse.

Then the English spoken here would in turn benefit from such as close

association.” Though it is sad, this scenario has not yet happened in

Sri Lanka despite the fact English has been in use for over 200 years.

Standard of language

One of the cardinal issues that the contributors deal with in the

publication is ‘standard languages’ or ‘language standards’ besides

hegemonising and de-hegemonising different variants of English that are

in contemporary use.

Although Manique Gunesekera and Arjuna Parakrama identify one or two

main dialects of Standard Sri Lankan English, Siromi Fernando has

identified four dialects of Standard Sri Lankan English and that there

is overlapping of the characteristics of diverse dialects among one

another to such a degree virtually obliterating the clear distinction

among them.

Citing Einar Haugen’s seminal paper “ Dialect, Language, Nation”,

Siromi Fernando explains at length the notion of a standard of language;

Haugen has stated in defining standards,“ …a standard language, if it is

not be dismissed as dead, must have a body of users. Acceptance of the

norm, even by a small but an influential group, is part of the life of

the language. Any learning requires the expenditure of time and effort,

and it must somehow contribute to the wellbeing of the learners if they

are not to shirk their lessons.

A standard language that is the instrument of authority, such as

government, can offer its users material rewards in the form of power

and position…The kind of significance attributed to language in this

context has little to do with its value as an instrument of thought or

persuasion. It is primarily symbolic, a matter of prestige ( or lack of

it) that attaches to specific forms or varieties of language by virtue

of identifying the social status of their users..Mastery of the standard

language will naturally have a higher value if it admits one to the

councils of mighty …in our industrialised and democratic age there are

obvious reasons for the rapid spread of standard languages and for their

importance in the school system of every nation.”

In the conclusion, Siromi Fernando states, “There is inconsistency in

the following rules in all the dialects. There has also been

sociological change in the description of the users of the dialects.

Apart from this, features of one dialect have begun to occur in other

dialects as well.

Hence since there are some confused patterns in the dialects at

present, although the general characteristics of each dialect can be

described, it is difficult to define clear rules. ”

Siromi Fernando’s contribution is noteworthy given the fact that she

has quite candidly explained the actual position with regard to the

existence of diverse varieties of Sri Lankan Standard English and that a

clear distinction can hardly be made among those varieties.

The entire discourse on Sri Lankan English or the homespun varieties

of English raises pertinent issues such as for whom these varieties of

English developed and the distinct purpose for such varieties would

serve, particularly in the domain of international relations and

commerce. It is also highly polemical whether these varieties of English

are acceptable to the population at large and the power wielders of the

society. What is obvious is that such varieties of English may

contribute to the growing body of world Englishes and would be of

importance from pedagogic perspectives and perhaps, to maintain English

as a potent class indicator as stated by Thiru Kandiah.

What is striking is whether the ‘standard’ Sri Lankan varieties of

Englishes have fulfilled the requirements according to the classic

definition of ‘a standard language’ apart from their indefinable nature.

There has been an attempt to compile a bibliography on Sri Lankan

English.

|