Furthering art thro’ saleability

By Dilshan BOANGE

‘Art for art’s sake’ is a romantic ideal that disregards the

‘marketability’ of the work, possibly to the extent that ‘price tagging’

is denounced as ungainly and to be frowned upon. But how far has that

taken the artist in surviving in this present day system is a question

that lies at the heart of the message conveyed through the artistic

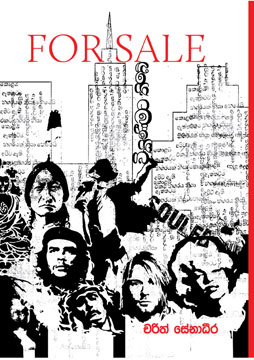

endeavour unveiled by Charith Senadheera on August 25 and 26 when his

book of Sinhala ‘poetry’ FOR SALE was launched followed by the opening

of his exhibition of visual art that also bore the same title.

The endeavour by Charith merits discussion with focus on his

conceptualisation of the book, which in my opinion cannot be simply

labelled a book of poetry since the contents are of a nature whose very

unconventionality states defiance of genre classifications, as well as

the ideas of this creative expressionist whose concept of ‘Visual

poetry’ was intended to be spotlighted in the exhibition. The endeavour by Charith merits discussion with focus on his

conceptualisation of the book, which in my opinion cannot be simply

labelled a book of poetry since the contents are of a nature whose very

unconventionality states defiance of genre classifications, as well as

the ideas of this creative expressionist whose concept of ‘Visual

poetry’ was intended to be spotlighted in the exhibition.

FOR SALE is Charith’s first artistic project done on a public scale

but his talents have reached audiences, although perhaps understated.

A product of Ananda College, Colombo he was the lyricist who wrote

the song Ananthayata yana para dige which became a popular hit among

young music lovers and became quite veritably the launching pad for

vocalists such as Kasun Kalhara and Indrachapa Liyanage. Charith is now

a designer at MAS having graduated with a degree in fashion designing

from the Moratuwa University and had been working on the publication FOR

SALE for nearly five years.

Initial impressions

One of my initial impressions about the exhibition on learning about

Charith’s professional and educational background was whether the

visuals were based on perhaps some designs he did while in university or

had some link or basis to what he would create for his place of

employment. The simple answer was a polite ‘No’.

“When graduates from any field of aesthetic studies go to work what

happens is they find their artistic passions can’t be pursued any

longer. Their artistic essence, their skills their knowledge, go into

serving the industry.” Thus the FOR SALE project was in certain ways

Charith’s way of breaking out of that matrix into which creative young

people become enmeshed. Perhaps it was a benign rebellion of sorts in a

way to show that a person with creative passions to create works of art

must not let their sparks for passionate expression become dulled along

the path to succeed professionally.

A point that becomes rather contentious perhaps when discussing on

the lines of what art should be in its purpose to serve the artist and

also society is how Charith views and projected as the central idea of

his project, that ‘saleability’ of art matters, and matters

significantly for the survival of both the artist and his art. He

positions this argument very specifically looking at the present state

of how Sinhala medium literature especially ‘poetry’ stands in a market

context to insufficiently remunerate the artist and the parties that

undertake to finance an artistic project.

Suffering

“An artist needn’t necessarily be a sufferer. And his life shouldn’t

be a tragedy. But people tend to think the inheritance of an artist is

suffering and poverty. “An artist needn’t necessarily be a sufferer. And his life shouldn’t

be a tragedy. But people tend to think the inheritance of an artist is

suffering and poverty.

That shouldn’t be so. He should be financially stable and have the

means to continue his work as an artist, by earning through his art.

Sadly that isn’t possible here in our country.” The project FOR SALE was

in that sense a spark of rebelliousness in trying to bring in objectives

of ‘market reach’ and give the ‘shape’ of a Sinhala medium book of verse

a newer positioning.

The ‘social politics’ of the venue have in this regard played a

significant role to help Charith in his objectives. The place was a

warehouse of the Park Street Mews set up where an upper market segment

of society can be reached.

It had created an opportunity to open the artistic endeavour of an

essentially Sinhala medium expressionist to audiences that included

foreigners who although may not be literate in Sinhala would possibly

appreciate the calligraphic elements that are centrally at play in his

art. The fact that some events of the Colombo International Music

Festival coincided with FOR SALE at the same premises had also worked to

Charith’s advantage.

Dividends

“Park Street Mews has a certain upmarket culture” Charith noted “For

a Sinhala medium practitioner having your work unveiled at a place like

this helps reach a stratum that generally wouldn’t make an effort to go

looking for events like the launch of a Sinhala poetry book held in some

of the more familiar places where the crowd is essentially the usual

faces. Having it in a place like this helped create that cross-section

which I really hoped for. To me it’s about creating the opportunity for

a larger audience to see my work and hopefully appreciate it.”

Before going to a more detailed discussion about the book and its

elements a focus on the one of the key ingredients and approaches to

characterise Charith’s work must be better grasped. One of the

conceptual underpinnings of the art form that he presented through FOR

SALE the exhibition is that the nature of his use of Sinhala is not to

be thought of as serving literature or art in a traditional sense.

Language as calligraphy

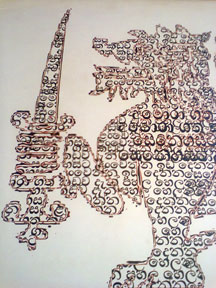

Language seen as words which can be deconstructed to alphabetical

characters can be seen as evincing, when looking at the manner in which

they have been employed, how Charith perceives words for their

calligraphic quality. Perhaps the artist also viewed them as having

aesthetic facets in terms of their curvature and appearance. It is

likely that such a quality is what is meant to reach out to attract a

person who cannot read Sinhala. But that does not mean the words don’t

construct meanings. Far from it; the ‘politics’ that are painted onto

the art are only too obvious when one takes a look at some of the pieces

that have themes of gender politics to nationalism inscribed

unapologetically. Language seen as words which can be deconstructed to alphabetical

characters can be seen as evincing, when looking at the manner in which

they have been employed, how Charith perceives words for their

calligraphic quality. Perhaps the artist also viewed them as having

aesthetic facets in terms of their curvature and appearance. It is

likely that such a quality is what is meant to reach out to attract a

person who cannot read Sinhala. But that does not mean the words don’t

construct meanings. Far from it; the ‘politics’ that are painted onto

the art are only too obvious when one takes a look at some of the pieces

that have themes of gender politics to nationalism inscribed

unapologetically.

One such piece is the one that has overlapping sentences that

translate as ‘sword brandishing’ ‘putting down’ and so on, forming the

image of the lion of our national flag. These pieces take the form of

what Charith classified as ‘Visual poetry’ which by his explication is

not a widely practised form of expression here although there have been

notable figures who had used it as a method.

In my own critical viewing which would take on an approach of looking

at the work for its resonance or conformation to what its classification

literally would translate or communicate, I feel the term ‘Visual

poetry’ must be ‘stretched’ in order to encompass Charith’s pieces,

since the words that form sentential meanings blending with images and

at times forming images and becoming patterns by itself do not fulfil an

element of poetry by virtue of the words alone.

William Blake was known to have fused verse with his paintings and

one may allude to such sources to find perhaps a more fuller sense of

the concept that seems to be the grounding for the term ‘Visual poetry’.

However, my own observations cannot make any declarations of absolutism

but merely provide food for thought.

Writing as readable images

“Seeing a picture with Sinhala words forming an image may be seen in

one way by a Sinhala reader and in a totally different way by a

foreigner when it is hung enlarged like any other picture on a wall.”

Arguably a facet of thinking working in the mind of Charith is his ideas

conceived as words taking the form of a modern Sinhala calligraphy.

He feels to ones who cannot read Sinhala the visual appeal in the

manner it has been assembled and patterned may spur curiosity to find

out what it means literally. That could in certain ways have a whole

other set of politics at work where perceptions are affected about a

visually appreciated piece to one that is then seen as ‘readable

material’. “I see many young people who have Chinese, Japanese words

tattooed on their arms and shoulders and such. Can they really read

those characters? When you ask them they tell you its meaning. That’s

something to think about. The visual attraction it has creates a

curiosity for us to learn what it means as ‘writing’.”

There is much truth in his argument that warrants contemplation on

what words and characters of a language we cannot read is worth to us?

Perhaps their ‘appearance’ their ‘form’ serves a purpose of

ornamentation.

The book FOR SALE

FOR SALE, the exhibition was also the launching pad of FOR SALE the

book which is something of a potpourri along the lines of Charith’s

conception of ‘Visual poetry’ as well as illustrations by his wife

Kithmini to enhance and complement the book’s visual qualities that come

by way of the verses that are arranged in figurative formations. As a

book, FOR SALE is rather problematic to simply label a book of poetry

since the idea of genre is not very well adhered to by the artist cum

poet. FOR SALE, the exhibition was also the launching pad of FOR SALE the

book which is something of a potpourri along the lines of Charith’s

conception of ‘Visual poetry’ as well as illustrations by his wife

Kithmini to enhance and complement the book’s visual qualities that come

by way of the verses that are arranged in figurative formations. As a

book, FOR SALE is rather problematic to simply label a book of poetry

since the idea of genre is not very well adhered to by the artist cum

poet.

“There are no more strict borders, as I feel, between genres of art.”

Said Charith whose idea of a genre defying endeavour is better depicted

through the book, than the exhibition of ‘visuals’. The foreword to the

book is by K. K Saman Kumara a name renowned in the spheres of

contemporary Sinhala writing. The principal review of the book at the

launch had been by him and a speech had also been made by Prof. Sarath

Wijesuriya the Sinhala don from Colombo varsity. And Charith said his

expectations of gaining a space for a wider cross-section of society was

achieved through having the book launch at his chosen venue.

“If people from the strata that frequent Park Street Mews come to

appreciate my poetry, I’m sure it may strengthen Sinhala writers who

generally don’t attempt to reach an audience like the people who you

would find in this kind of environment.”

When Charith expresses thus one is impelled to query how much of his

Sinhala poetry would be found ‘accessible’ from a point of language to

persons who may not be able to read Sinhala, the prime example being

foreigners who are regular patrons of the venue. Perhaps the exhibition

FOR SALE is the main focus for that segment whilst urban upper class

readers who would not generally mark on their schedule diary a Sinhala

poetry book launch would be the irregular additions to a hopeful

readership.

But the book as said of it earlier is not the general book of poetry

that one comes across. The poetry is entirely of the free verse form yet

its assortment of content renders it something of a book of drawings or

sketches as well. To Charith a book is not the inner contents on the

pages alone. “A book is the whole product. It’s not just the words. That

is why I made the jacket of the book the way it is. The design is

intended to be appealing and persuade a person to pick it up and turn

the pages inside.”

What lies inside?

And what lies in the pages held between the cover? The assortment is

as said before remarkably diverse. The free styled verses are easy going

and flow in a balance of expressions which capture a sense of the

literary and colloquy. There are sketches that are line drawings. And of

course a host of ‘Visual poetry’. The verses are of themes that range

from love and heartache to sensuality to war to solitary contemplations.

On page 30 is a single liner which would translate to English as –‘If I

only I could see myself through your eyes.’ Certainly in the more

classical and traditional sense such a composition may not count as a

fully developed ‘poem’ but the more modern contemporary expressionism

that is entering the Sinhala cannon would now provide room for free

flowing prosaic verse to be considered as poetry in the true sense of

the word. Another such single liner is on page 39 which translates to

English as ‘Mirror, at least now show me my own face.’ Touching on the

theme of voyeurism the poem on page 50 translates to English as

–‘Through the key hole of the locked door, paradise...?’

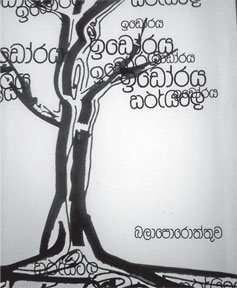

‘Visual poetry’ in FOR SALE is to be found in several types. One is

where words have been made part of sketched line drawings as what is

found on page 82 which shows something of a fatigued male figure

dragging his feet with wings shaped by rows of words that make up that

translate as –‘Weary wings’. And then on page 48 which is red in colour

is a swastika made of the Sinhala word for ‘Democracy’ in black print. ‘Visual poetry’ in FOR SALE is to be found in several types. One is

where words have been made part of sketched line drawings as what is

found on page 82 which shows something of a fatigued male figure

dragging his feet with wings shaped by rows of words that make up that

translate as –‘Weary wings’. And then on page 48 which is red in colour

is a swastika made of the Sinhala word for ‘Democracy’ in black print.

Ideological directions?

What is Charith’s approach meant to serve from a point of ideological

framework? The somewhat not very pleasant question was posed taking into

consideration how his outlooks and intentions conveyed through his

project spoke of the need to reach for markets, and at that the

inclusivity of the upper social strata. “That is a good question” was

what Charith began his response with when asked if his views expressed

through FOR SALE are of a ‘free market’ oriented rightwing politics. “I

don’t think today there is much of a difference between left and right

politics since its much of the same people who have been crossing from

one camp to the other, and back again. As I see it there is no

difference.”

Inference of lines being blurred between the leftism and the

rightwing in our present day context may be one way for Charith to

position a pragmatism to his project’s projected ideas rather than

giving it a ‘camp specific’ purpose. But surely there is a sense of

calling upon the artist to become more receptive to the opportunities of

a market oriented system, and thereby reap its benefits.

FOR SALE is a project of creativity that was of two components that

have at its core a message that Art being made as ‘saleable’ is not

vulgarism. Charith’s creativity through FOR SALE has been put up for

sale in two forms, as exhibits and as a book.

How ‘Visual poetry’ in the form of ornamentations or art pieces will

work to capture a market and how books of the nature of Charith’s

publication will capture readers to be a financially viable enterprise

can be seen only with the passage of time and the entry of more creative

artists of the likes of Charith who will offer more art intended for

sale.

There is no doubt that FOR SALE stands on a platform of innovative

thinking and conceptualisation and by understanding how creative

expressions can touch the pulse of audiences and the markets they form,

perhaps these novelties can become highly valued and prized in an ever

modernising world with its expanding opportunities.

|