Sri Lankan cinema +66

By Kalakeerthi Edwin Ariyadasa

"The violent effort, which the Sinhala film-producers thought it

necessary to make, in order to hang a handful of characters on some

trivial peg of a plot, has given us a film-fare, strongly reminiscent of

the bioscopic and silent beginnings of the cinema.

|

|

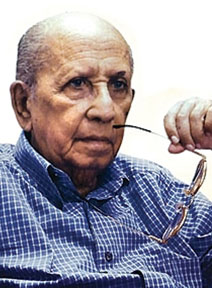

Dr. Lester James Peries |

... If the Sinhala film were to develop at the expense of Sinhala

drama - as it has done hitherto, the people to whom art and culture

matter will not find it too happy a prospect... But, it is quite

essential that the Sinhala film-makers who have discarded the stage for

the screen, should remember that the film requires a technique of

handling different from the state..."

Edwin Ariyadasa

(From an article titled "The Sinhalese Film - A wife and Five

Puppets" contributed to the Observer Pictorial - 1950).

The 66th anniversary of Sinhala cinema dawned, illumined by the

ethereal glow of the long-awaited Sinhala film-epic "Sri Siddhartha

Gautama" - the cinematic narration of the sacred life of Siddhartha

Gautama. This exquisite film-event, holds an unprecedented promise for

the new era of Sri Lankan cinema.

In historical hindsight, we note that the first Sinhala film, that

ushered in the tradition of Sri Lankan cinema, was, strangely enough

"Broken Promise," released on January 21, 1947.

The processes that eventually led to the presentation of "Broken

Promise", as the first-ever Sinhala film, were determined not by

creative, artistic or cultural factors but solely by economic and

financial considerations.

Back then, the world was still in the throes of the aftermath of a

global war. In Sri Lanka (Ceylon then) near-universal employment and

war-time inflation ensured a steady flow of cash, bringing in its wake a

euphoric sense of sudden affluence. The ever-present threat of death and

destruction, inevitable in times of war, though muted to an undertone,

unleashed a frenzied indulgence in sensual pleasures.

Entertainment

The most widespread form of entertainment available to the people,

was the legitimate theatre. In the new centres of human settlement,

called into existence, through the exigencies of the war-effort, the

itinerant theatrical companies, received an adoration that seemed to

verge on the religious. The Sinhala actors and actresses, who became

mass-idols of the day, could not cope adequately with the

ever-burgeoning demand for their plays.

In the nature of things, the live presence of a given actor or

actress could happen only at one place at one time. In such a context,

if the theatre companies were keen to rake in the available shekels in

larger quantities, they had to devise a method of multiplying the

appearance of these players, so that, they could perform simultaneously

at several centres.

The crucial question was, how could this 'miracle' be worked out?

Cinema, of course, held the key to the solution of this problem. The

proposition was simple: convert the stage-play into its photographed

version - and, you get a simultaneous island-wide audience for your

"play". This exactly was the thinking that resulted in the birth of

Sinhala cinema.

At the height of this preoccupation with the cinematographed stage

play-that is approximately during the latter half of 1946 - Sri Lanka

did not have even a war on while movie camera - not to say anything

about studios or other facilities for the product of films locally.

An artistic and economic pilgrimage had to be made to South India -

as that was the film-making location closest to us. And, that was how,

on January 21, 1947, "Broken Promise" (Director:B.A.W. Jayamanne) came

to be released as the first-ever Sinhala film. While maknig history that

way, it became the first, in a series of Sinhala films of South Indian

origin.

Technical facilities

The historical necessity that compelled the pioneering Sinhala

film-makers to seek South Indian technical facilities and directorial

talents, imparted a marked theatrical bias to the first Sinhala film.

Writing in the Observer Pictorial for 1950, under the title "The

Sinhala Film - A wife and five puppets" I made my observations of the

Sinhala cinema, which was only three years old then. (I must confess

though, that the title has a slight trace of cynicism). There I said the

following (among other things).

"Seeing the camera utilised merely as an instrument to record events

that take place in chronological order, would have been immensely

satisfying to the film-goers of the early days of cinema. But today

(1950) when cinema audiences get an opportunity of seeing the power the

film camera is capable of the only thing that compels one to see these

films, is the fact that they are in Sinhalese."

Formula films

It is to the credit of the Sinhala film-goers that he grew weary of

this kind of film-fare, within the first decade itself. The people

discovered before long, that what was offered to them was neither

Sinhala nor cinema, in the real sense.

The individual who endowed a new incarnation on the formula - ridden

Sinhala cinema, is of course, cinema-savant Lester James Peries. By

common consent LJP is the supreme hero of the 66 years of Sinhala film

history.

|

|

A scene from Kadawunu

Poronduwa |

At a celebration, organised by the National Film Corporation, great

Lester James Peries, was especially felicitated, as the personality of

the 66 years of Sinhala cinema.

Lester James Peries introduced a professional elegance to the

business of film-making in Sri Lanka, going counter to the "creative

shabbiness" that generally prevailed in that field, prior to the

appearance of his Rekawa (Line of Destiny, 1956).

Rekawa was shot almost entirely on location in Sri Lanka, at a time

when outdoor shooting was a rare phenomenon both in South India and Sri

Lanka. The effort to instil the 'Sinhala feel and the cinematic

discipline' into Sri Lankan cinema was initiated by LJP, when he based

his films firmly on themes deeply rooted in our native soil.

Enthusiasm

In the enthusiasm to shower praise on LJP, as a pioneer in the

indigenous tradition of film-making, many tend to overlook a yet another

profound contribution he made to Sri Lanka's cinema scenery.

In the off-quoted phrase - T.S. Eliot, revolutionary poet and

aesthetic guru - declared that the purpose of criticism, is the

"Elucidation of works of art, and the correction of taste."

Lester James Peries, waged a valiant battle - single-handedly at

first - to correct Lankan film-goers. LJP, weaned the Sri Lankan film

and engendered in them a taste for quality film-making, that probes the

deeper larger of human existence, utilising cinema-art with a telling

deptness.

Lester elevated Sri Lankan cinema to global heights. This resulted in

the pronouncing of Lester James Peries' name with the same hushed tones,

as those of Akira Kurasawa, Satyajith Ray and Ingmar Bergman.

Establishment

In the realm of Sri Lankan cinema, Lester James Peries is decidedly

the unassailed "Establishment". In any field, people respond to an

establishment in one of two ways.

They may resent it, revolt against it or denounce it. Or else they

would adore it, admire it, esteem it or emulate it.

Whatever may be the attitude adopted, a well-entrenched establishment

generates the dynamism that ensures progress. No worthwhile discourse on

cinema is possible, without Lester's name assuming centre - stage in

that kind of colloquy.

Lester James Peries' far reaching influence, began to be felt

especially after his Gamperaliya (The Changing Village).

Released in the mid-sixties this symbolised the climactic meeting so

far in the history of Sri Lankan cinema, between an exclusively Sinhala

theme and an essentially cinematic interpretation. Gamperaliya assumes a

special importance for several other reasons as well.

Award

In 1965, it was the "Golden Peacock" from India. This award was a

tremendous ego-boost for Sri Lanka's film-psyche. From then on, Sinhala

film began to acquire a prestige it did not enjoy earlier.

People no longer felt that they needed to be apologetic about the

Sinhala film, like an urban sophisticate about the coarse ways of his

country cousin.

Gamperaliya established Lester James Peries, with a distinct

"imprint" of his own. He could no longer fail but only fluctuate.

In his 57-year long film career his sustained effort has been to

build a cinematic conduit to one heart of Sri Lankan culture.

Many personalities associated with the 66 year-long Sri Lankan cinema

history, either as directors, actors, actress and technicians have

displayed widely recognised talents.

Progress

In the recent years however, the progress has been uneven both in

quality and quantity.

The present chairman is committed to wisher in a new era for Inhalant

cinema, privilising the construction of state-of-the-art cinema

theatres.

It is essential to build an indigenous cinema culture, that will

uphold our cinema works, giving them the same prestige as what we give

to our sacred edifices, our hydro-culture, our art now literature and

our gentle style of existence.

Building a cinema culture is not equivalent to the creation of

film-bufts and gossipy other about men and women of cinema.

It is a much more profound phenomenon, that will lead to the

emergence of generation possessing high-well-informed deference for the

indigenous film icons. This needs an extensive discourse.

Such a fruitful discourse should be initiated as an outcome of our

celebration of 66 years of Sinhala cinema. |