Endangered sharks return to Bahamas 'home'

Oceanic whitetip sharks return home to protected Bahamas waters,

surprising scientists.

|

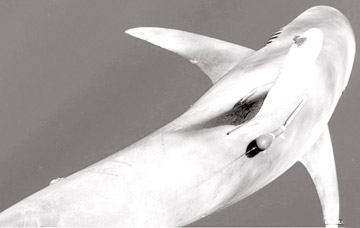

The Oceanic whitetip shark |

Previously thought to be wide-ranging animals, a tagging survey has

revealed that the sharks frequently revisit the same areas around the

island.

Conservationists have listed the sharks as Vulnerable globally and

Critically Endangered in parts of their range.

Experts suggest that the island nation's marine protected area is

assisting the species.

The findings are published in the online journal PloS One .

Oceanic whitetips are named for the distinctive white flashes at the

end of their fins.

They are opportunistic predators with powerful jaws and as such are

considered one of the more dangerous sharks to humans, although the

number of unprovoked attacks on people is small.

"Of all the sharks that live in the open ocean, they're the ones that

have really declined a lot in the last few decades," said Dr Demian

Chapman of Stony Brook University, New York, US, who led the study.

"They've gone from being one of the most abundant large vertebrates

on the planet to being considered quite endangered."

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature has listed the

sharks as Vulnerable due to over-fishing for their meat and leather, and

accidental by-catch.

"Oceanic whitetips frequently take bait meant for other species like

tuna and swordfish," said Dr Chapman, explaining that their fins are

prized for shark fin soup.

"Fisherman will take all of these sharks that were incidentally

hooked and they will take their fins, and that is fatal to the shark."

Banned shark fishing

In July 2011, the Bahamian government banned shark fishing in all

240,000 square miles of the country's waters.

According to the Pew Charitable Trusts which works to establish shark

sanctuaries, including the one in the Bahamas, the animals provided $78

million to the country's economy in tourism over 20 years.

"Tourism is a big part of the Bahamian economy, within that diving

and shark diving in particular is very valuable," said Liz Karan,

manager of Global Shark Conservation at Pew.

"I think there's interest in that particular area just because it's

one of the few places left in the world that have relatively healthy

shark populations."

"So without too much effort you can go and have an experience that's

really unique."

In May of the same year, advocates assembled to support the sanctuary

announcement.

Dr. Chapman joined forces with these dive tour operators,

recreational fishermen, scientists, engineers and conservationists in a

project aiming to understand more about oceanic whitetip sharks.

"We thought it was amazing that nobody was doing research on them in

the Bahamas because this is the only place in the Atlantic where you can

reliably find them," said Dr Chapman.

Previously, only one oceanic whitetip had ever been successfully

tagged, but the experienced team were able to follow 11 of the animals.

"They're very bold, they come right to the side of the boat... but

these sharks are really smart when it comes to baited hooks," said Dr.

Chapman.

He described the mature adult sharks as "cagey veterans" who had

likely survived encounters with hooks in the past and so were wary about

the researchers.

The sharks they were able to catch were fitted with satellite tags

near their dorsal fins which provided up to eight months of data,

covering temperature, light, depth and location.

Considerable amount of time

The team found that although the sharks travelled far and wide as

expected, they also spent a considerable amount of time in Bahamian

waters.

"I was not surprised that they went long distances, but I was

surprised that they turned right back around and returned to the

Bahamas," Dr Chapman told BBC Nature .

"We really think of these oceanic whitetips as ocean wanderers, we

didn't think we'd see such a strong pattern of return migration."

According to Dr Chapman, the results suggest that a ban on long-line

fishing in the 1990s, reinforced by the more recent sanctuary status of

the waters, combines to make the Bahamas a safe haven for the sharks.

"I think one of the key questions about sanctuaries is 'do they

work?' and this is a clear example that shows sharks benefiting from a

sanctuary designation," said Ms Karan.

"As the migration patterns show, they do leave the sanctuary area for

part of the year and during that time they are vulnerable to fishing

pressures and the dangers of being caught," she warned.

The team is travelling to Bangkok, Thailand next month to present

information on the species to the Convention on International Trade in

Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora conference where countries

will vote on the regulation of the trade in shark fins.

They are also working on a further tagging project, following the

movements of males and pregnant females to get more information on the

sharks' breeding habits and a full picture of how the population is

faring.

- BBC Nature

|