Text as a fabric of signs

In the previous column on ‘Of Grammatology’, we concluded with an

observation by David Potts who said that ‘The closure’ (or bounds) of

the logocentric epoch lies in the recognition of this radical

incoherence: the concepts of being, truth, sense, logos, and so forth,

cannot be made good within the logocentric framework. In the previous column on ‘Of Grammatology’, we concluded with an

observation by David Potts who said that ‘The closure’ (or bounds) of

the logocentric epoch lies in the recognition of this radical

incoherence: the concepts of being, truth, sense, logos, and so forth,

cannot be made good within the logocentric framework.

It is the work of deconstruction to expose the tail-swallowing nature

of these concepts and thereby reveal the bankruptcy of logocentrism.

Deconstruction does not attack the concepts of the logocentric epoch

from the vantage point of a new epoch but from within the logocentric

epoch--the only place from which they can be conceived at all . ”

Derrida postulate the thesis that ‘there is no linguistic sign before

writing’; “The exteriority of the signifier is the exteriority of

writing in general, and I shall try to show later that there is no

linguistic sign before writing. Without that exteriority, the very idea

of the sign falls into decay. Since our entire world and language would

collapse with it, and since its evidence and its value keep, to a

certain point of derivation, an indestructible solidity, it would be

silly to conclude from its placement within an epoch that it is

necessary to “move on to something else,” to dispose of the sign, of the

term and the notion.

|

|

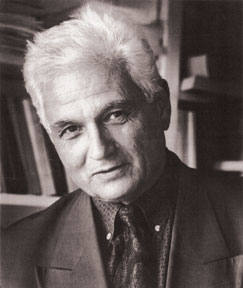

Jacques Derrida |

For a proper understanding of the gesture that we are sketching here,

one must understand the expressions “epoch,” “closure of an epoch,”

“historical genealogy” in a new way; and must first remove them from all

relativism.

Thus, within this epoch, reading and writing, the production or

interpretation of signs, the text in general as fabric of signs, allow

themselves to be confined within secondariness.

They are preceded by a truth, or a meaning already constituted by and

within the element of the logos. Even when the thing, the “referent,” is

not immediately related to the logos of a creator God where it began by

being the spoken/thought sense, the signified has at any rate an

immediate relationship with the logos in general (finite or infinite),

and a mediated one with the signifier, that is to say with the

exteriority of writing.

Metaphoric mediation

‘When it seems to go otherwise, it is because a metaphoric mediation

has insinuated itself into the relationship and has simulated immediacy;

the writing of truth in the soul, opposed by Phaedrus to bad writing

(writing in the “literal” and ordinary sense, “sensible” writing, “in

space” the book of Nature and God’s writing, especially in the Middle

Ages; all that functions as metaphor in these discourses confirms the

privilege of the logos and found the “literal” meaning then given to

writing: a sign signifying a signifier itself signifying an eternal

verity, eternally thought and spoken in the proximity of a present

logos.

The paradox to which attention must be paid is this: natural and

universal writing, intelligible and nontemporal writing, is thus named

by metaphor. A writing that is sensible, finite, and so on, is

designated as writing in the literal sense; it is thus thought on the

side of culture, technique, and artifice; a human procedure, the ruse of

a being accidentally incarnated or of a finite creature. Of course, this

metaphor remains enigmatic and refers to a “literal” meaning of writing

as the first metaphor.

This “literal” meaning is yet unthought by the adherents of this

discourse. It is not, therefore, a matter of inverting the literal

meaning and the figurative meaning but of determining the “literal”

meaning of writing as metaphoricity itself. “

Modification

Derrida argues that writing itself is metaphoricity; “ In “The

Symbolism of the Book,” that excellent chapter of European Literature

and the Latin Middle Ages, E. R. Curtius describes with great wealth of

examples the evolution that led from the Phaedrus to Calderon, until it

seemed to be “precisely the reverse” by the “newly attained position of

the book”. But it seems that this modification, however important in

fact it might be, conceals a fundamental continuity.

As was the case with the Platonic writing of the truth in the soul,

in the Middle Ages too it is a writing understood in the metaphoric

sense, that is to say a natural, eternal, and universal writing, the

system of signified truth, which is recognised in its dignity. As in the

Phaedrus, a certain fallen writing continues to be opposed to it.

There remains to be written a history of this metaphor, a metaphor

that systematically contrasts divine or natural writing and the human

and laborious, finite and artificial inscription.

It remains to articulate rigorously the stages of that history, as

marked by the quotations below, and to follow the theme of God’s book

(nature or law, indeed natural law) through all its modifications.”

In summerising the chapter, Potts says, “What is needed is a wholly

new conception of language which puts writing first. Rather than

signifying signifieds in a series terminating ultimately in a

transcendental signified, written signifiers according to the new

conception signify only other signifiers, not because of a failure of

the signifieds but because there is no need of them.

There is only a perpetual chain or circle of signifiers, an endless

“play of signifying references”, which is never anchored to anything.

“This, strictly speaking, amounts to destroying the concept of ‘sign’

and its entire logic”.

The key concept is differance (with an “a”), which implies both

difference and deferance. Every signifier is inherently different from

what it signifies, and we should uphold this difference, not seek to

erase it in a misguided quest for presence. By the same token every

signifier defers recognition of what it signifies, and we must embrace

this also.” |