Immortalising the fate of the faceless

By Dilshan Boange

All art stems from some form of human experience. Deciphering the

experience embedded within the aesthetic creation could lead to

revelations that may be either highly individual or collective, but

nevertheless rendered as a personal interpretation. What of these lie in

the work of theatre titled Cafila that was staged as a performance of

the Colombo International Theatre Festival recently at the British

School in Colombo auditorium, began brewing as questions in my mind, as

I watched the students from the Flame School of Performing Arts in Pune

bring to life on the boards a story that spoke of fears and hates and

the desire for harmony amongst ordinary people set in a time that is now

settled in the annals of history in the Indian subcontinent as -the time

of the 'partition'. The play was directed by Prof. Vidyanidhee Vanarase

who is the current Dean of the Flame School.

|

|

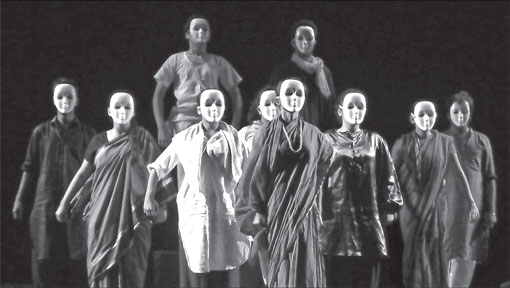

A scene from Cafila |

The utilisation of actors showed a pragmatic approach considering

this was a student performance brought from overseas to perform at a

festival in Colombo. Although characters such as the chief narrator were

designated to one actor and were present throughout the scene, certain

players who exited the stage re-entered as new characters. And the props

too were worked out with logistical concerns as it became shown as the

play progressed. But in all fairness to the people behind the Cafila

production it must be said that a barrenness did not pervade the stage

since the human element was well spread out to locate action that was

meant to be both inside and out the train carriage.

Identities and searches

Cafila is about identities and their politicisation. It is about the

power of ethno-religious affiliations for collective identities and how

it can spiral into madness. It is in reading this work of theatre in the

context of a story related to conflicts based on matters of ethnicity

and demarcating spaces for nationhood that I find Cafila a drama that

has much resonance to Sri Lankan audiences of today in this post war

scenario.

The opening is a two player scene where the story is of a Muslim

father caught in the chaos of ethnic violence in the time of partition.

It's a narrative fused with role play. The search is for Shaheena, the

daughter who is found in a hospital half dead but fortunately alive. The

opening scene in that sense was a prologue of sorts that was like a

stage setter for the story's background in terms of understanding the

mental traumas, agonies that people underwent. Sitting at the very

frontal edge of the stage the young man and young woman who played their

roles brought out a sense of the conversationalist as much as the

raconteur when functioning as narrators.

With the shifts in the incidents being described and tonally

indicated to the audience of how the situation was changing in its

emotive aspects I felt the scene was meant to be something of an

exercise to the audience to imagine in their heads the picture of

anguish described verbally based on the oral attributes of the

narrators' discourse.

The climax of that scene was when the man, whose attire clearly

showed his ethnicity to be Muslim, jumped off the stage and ran into the

aisles between the seating blocks in the audience space, bringing to

life the frantic father who is relentlessly in search of his daughter.

In this regard I feel the young actor Nikhil Gadgil must be

congratulated for pulling off a compelling shift in his mode as a

performer whose presence depicted several facets of narration.

The precursor performed, the theatre gave way to the gentle darkness

to allow the stage to dawn what was the bulk of the play. The train

journey between border, as Pakistan was being carved out of British

India as a separate nation, and mass exodus between the would be

national border was taking place. The stage came to light with a group

of actors sitting on a wooden box like prop which presumably meant to

depict a booth in a train carriage. And though the ones who would talk

and be the drivers of the narrative bore faces to the audience there

were sets of people wearing a uniformly moulded plain white mask

reminiscent of the countenance of the phantom of the opera.

The faceless masses

It was a symbolic depiction of facelessness. The position of the

masses. Another element which is not visual but acoustically connects

with this message of facelessness is the monotonous way in which at a

certain point in the scene, the passengers intone the word 'Waiting', in

somewhat of a flow mimicking the chugging of a train. They were people

made to feel as though in a perpetual wait. The monotony denoted their

haplessness as well as denied them of any individual tones and accents

at that moment. In their choral intonation they became a collective of

people whose acoustic expression made them (metaphorically) faceless.

Facelessness is possibly one of the surest inheritances of the

masses. In India only gods and celebrities have faces. Anyone else is

just a speck in the vastness of the landscape. It is this reality of

India with its increasing populace that is depicted with the symbolism

of 'defacing' the actor with a mask that establishes the erosion of

individuality. I make these observations as a Sri Lankan whose

commentary can certainly be looked at as a cultural comparison. My

sentiments may perhaps be alien to an Indian reader's perceptions, while

possibly being fully acceptable to the Sri Lankan mindset. And for the

record I make no sweeping statements.

The Hindi limitation

A work of art when discussed analytically can seldom be completely

devoid of the commentators own subjective outlook. It is in this sense

that this review must be read as written by a Sri Lankan critiquing an

Indian play that contained parts of Hindi dialogue which was admittedly

outside my scope of lingual comprehension. Therefore I cannot purport to

have understood every word in the dialogues. And the reader is hereby

forewarned that my observations have limitations due to the language

barrier that existed between the work and me.

On the aspect of acting it must be noted that the manner in which the

players who symbolised the train commuting masses at the windows,

holding up to their masked faces wooden window frames, and becoming part

of the motionless stage set, showed their training and discipline as

practitioners of theatre. Their training that made them become perfect

props dissolved of human motion. Perhaps that was how some people back

then during the actual crises that erupted at the time of the Partition

survived those horrendously turbulent times in British India -by

becoming part of the landscape and shedding their human voices to escape

the wrath of any who sought to wreak carnage upon whoever was

undesirable to their vision of shaping human habitations. Human

habitations called nations based on a demographic vision of territory.

The assumption of roles by the players sitting together as the

central narrator -the grandmotherly looking Muslim lady with her sari

covering her head like a shawl, addressed as Amma by her fellow

travellers - describes the personae on board the train may be read as

how this play is about setting the story back in time, which is quite

different to the India of today and the present generation who didn't

actually live through the partition. In this sense this work of theatre

can be thought of as reliving the times, re-entering the skins of those

who faced the turmoil of the partition, from a place in present time.

Thereby the players may have depicted in their performance a narrative

mode of journeying between generations in telling the tale called

Cafila.

Demographics and power

Cafila is about demographic specifics and politics of demography in

the strictness of ethno-religious issues within the framework of

territories designated as politically demarcated. One of the main

indications of how demography works in this context of conflict where

the actors are located in a space that is said to be motional is how the

character of the 'Patan' is played out in the story. Being a Sri Lankan

when I heard the word Patan my mental references related to the

ethnography in Afghanistan.

I recalled what I remembered of watching the movie The Kite Runner. I

took the Patan to be of an ethnicity akin to some of the warlike Afghan

communities. The role of the Patan was intriguing to read in the context

of the politics of demography in the play. He is not opposed by anyone

and pretty much gets his way throwing his weight about wielding a staff

that he uses as a tool of aggression. The way the Patan assaults a

person trying to clamber on board the train with their belongings shows

that civic mindedness and empathy for others had been eroded, and how

none dared to intervene against the Patan showed how 'survival of the

fittest' was gaining ground as the valid principle.

The babu's indignation

The only opposition that comes in the way of the Patan is by the

lowly 'babu' who is initially taunted and demeaned by the aggressive

pole wielding turban wearer. The character of the babu is what works

with the character of the Patan to drive home the message about the

conflict being one that has its fluxes based on demography. The babu

when designated by the chief narrator at the outset of the scene shows

that it was a role which was clearly the least popular. The unhidden

dislike in the face of the player when fated to play the babu indicated

that his is a status that is not privileged. The demeanour of the babu

suggested that he was possibly of an oppressed community. Until the

train arrives in Amritsar the Patan's reign of bullying is unchallenged.

It is when the train's stop at Amritsar the babu gains an instant boost

of courage on the knowledge that perhaps his identity holds sway over

there. The fellow travellers intervene to make the babu desist from

avenging the indignities he was subjected to by the Patan. And finally

the aggressive man leaves the carriage to board another where all

passengers are of his own Patan ethnicity and thereby more to his

liking. Demographic realties at work, in certain ways, one may say.

It is interesting how it is the one whose demeanour suggested he was

the lowliest who rose up with resistance against the oppressor, which in

a way reinforced that Shakespearean wisdom from Henry VI Part 3-"The

smallest worm will turn being trodden on".

One of the striking questions spoken to the audience, reflective of

what may have been the more communally concerned matter for the Muslims

on board is said by the old Muslim lady. Will Mohammed Ali Jinnah move

to Pakistan or remain in Delhi? A very potent and pertinent question one

may observe given the fact that it was the late Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad

Ali Jinnah who founded Pakistan although initially the struggle for

Indian independence was fought together by leaders of all Indian

communities. It is possible thereby to read from this aspect of the

story that it was their respective community's leader that each Indian

in the struggle for independence followed and placed faith in. And so in

that context perhaps the average Indian caught in the chaos of the

Partition was wondering where their respective leader was leading them

to? And where would that leader in fact place himself territorially,

since it is after all a matter to do with territory and who lives where?

'Grandma Swati'

On the matter of the portrayal of the central narrator, Swati Simha

who brought to life the Amma was superb in delivering her role;

commanding the spotlight through her tone and facial expressions. She

was a compelling and convincing grandmotherly storyteller. She sounded

very much Hindustani and was (South Eastern) Asiatic in a manner

relatable to Sri Lankan sensibilities being very much an old talkative

granny whose endearing demeanour had dramatic expressiveness that keeps

listeners focused on every word and gesture. The India seen today is not

what the British acquired to their empire and celebrated as the 'Jewel

in the Crown'. It was a much larger landmass. A landmass which was

carved into separate states, to address issues that were bequeathed to

the people of the subcontinent once the white man left. The Partition

was possibly a political phenomenon that the people of India are yet to

fully get over. It created Pakistan which possibly made the ultimate

statement on an impossibility to realise a lasting post independence

harmony between Hindus and Muslims who shared the subcontinent prior to

the arrival of the British. Pakistan was possibly the inevitable

statement about territorialisation of lands in terms of ethno political

classifications.

What can the people of India or Pakistan learn from Cafila for their

respective futures? As convenient as partition was as a political

manoeuvre for the power holders, reunion between Pakistan and India in a

common nationhood is now next to impossible. It shows that once

separated on lines of ethnic or religious difference, it is a finality;

and the restoration to a state of olden times is but a dream.

Perhaps there are still those who are now the fading sunset in India

and Pakistan who have memories of being one nation called Bharatha

deshaya, and who would rejoice beyond description at its restoration.

But what can Cafila teach the people of today in the subcontinent that

lays separated from Sri Lanka by the Palk Strait, which to some is just

a mere swimmable strip of seawater?

There are clamours in India for greater devolution of power. The

creation of Uttarakhand from Uttar Pradesh in November 2000, and the

agitations in Andhra Pradesh by the 'Telangana movement' for the

creation of a new separate state of Telangana show how administration

wise the need for divisional attention is required. Yet does that take a

dimension of ethnicity or religion as the basis? And thereby sow seeds

for separatism for a complete breakaway for autonomy from India's

central government? I don't think so. These divisions don't show a

disintegration of territorial cohesion in terms of the Indian

Nation-State. But it was quite a different case in the phenomenon called

'partition'.

Nationhood and separatism

The present day sense of nationhood and its intra divisional growth

of administrative territories in India is a process by which the

people's needs are addressed within the context of being Indian and

being part of India. Their larger sense of national identity is never

compromised and that is India's strength in showing its unshakable sense

of nationhood. That is India's awesomeness. A vibrant multiethnic

diversity, which rallies together under the common banner of Indian

nationality.

There is much that Cafila can speak to present day Sri Lanka which is

now looking at reconciliation and rebuilding cohesion between

communities in the context of the post separatist war against the LTTE.

What resulted in British India that is called Partition was not

retractable. That is one of the principal messages Cafila can deliver to

an audience. And that once the wheels of political demarcations of

territory spurred by prejudices based on religion and ethnicity are set

in place, the masses follow the discourse with hardly any critical

introspection.

The unrecorded sufferers

It was not Jinnah or Pundit Nehru who suffered in that train

carriage, but Indians whose fate was to merely move with the chugging

train. 'Waiting, waiting, waiting...' until their journey's end is told

to them. Told as a declaration of statesmanship like what is heard when

Pundit Nehru says those immortal words "when the world sleeps, India

will awake to life and freedom" thereby fulfilling their 'tryst with

destiny'. Words immortal, played over the sound system, in the very

voice of India's first premier that has been recorded for posterity mark

the end of the play, as the gentle darkness descends to enclose

all.Perhaps with no irreverence intended to their past, of their

struggle for freedom from British oppression, for which cause sacrifices

were made by Brahmin and coolie alike, Cafila raises questions as to how

much of the voice of the people caught in the horrors during the

Partition, that created mass exoduses across the line that would birth

new nations, was heard or recorded for posterity?

While the whole world probably heard the impassioned words of Pundit

Jawaharlal Nehru to declare India's new birth, how many cared to listen

to the wails and crying of the subaltern whose grief was tragically

consequential to India's and Pakistan's search for nationhood? Indeed

one may wonder, whether they who suffered unheard, even heard the words

of their own leaders at those hallowed hours when they declared their

respective nations to have been born (?). |