Fossil of great ape sheds light on evolution

Researchers who unearthed the fossil specimen of an ape skeleton in

Spain in 2002 assigned it a new genus and species, Pierolapithecus

catalaunicus...

They estimated that the ape lived about 11.9 million years ago,

arguing that it could be the last common ancestor of modern great apes:

chimpanzees, orangutans, bonobos, gorillas and humans.

|

|

A University of Missouri integrative

anatomy expert says the shape of the specimen’s pelvis

indicates that it lived near the beginning of the great ape

evolution, after the lesser apes had started to develop

separately but before the great ape species began to

diversify. |

Now, a University of Missouri integrative anatomy expert says the

shape of the specimen's pelvis indicates that it lived near the

beginning of the great ape evolution, after the lesser apes had started

to develop separately but before the great ape species began to

diversify.

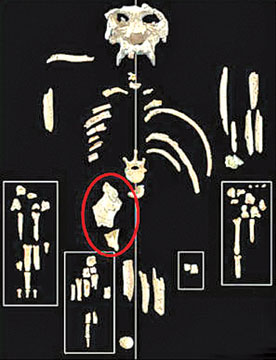

Ashley Hammond, a Life Sciences Fellow in the MU Department of

Pathology and Anatomical Sciences, is the first to examine the pelvis

fragments of the early hominid.

She used a tabletop laser scanner attached to a turntable to capture

detailed surface images of the fossil, which provided her with a 3-D

model to compare the Pierolapithecus pelvis anatomy to living species.

Hammond says the ilium, the largest bone in the pelvis, of the

Pierolapithecus catalaunicus is wider than that of Proconsul nyanzae, a

more primitive ape that lived approximately 18 million years ago.

The wider pelvis may be related to the ape's greater lateral balance

and stability while moving using its forelimbs.

However, the fingers of the Pierolapithecus catalaunicus are unlike

those of modern great apes, indicating that great apes may have evolved

differently than scientists originally hypothesised.

Pierolapithecus catalaunicus seemed to use a lot of upright behaviors

such as vertical climbing, but not the fully suspensory behaviour we see

in great apes alive today," Hammond said.

"Today, chimpanzees, orangutans, bonobos and gorillas use

forelimb-dominated behaviours to swing below branches, but

Pierolapithecus catalaunicus didn't have the long, curved finger bones

needed for suspension, so that behaviour evolved more recently."

Hammond suggests researchers continue searching for fossils to

further explain the evolution of the great apes in Africa. "Contrary to

popular belief, we're not looking for a missing link," Hammond said.

"We have different pieces of the evolutionary puzzle and big gaps

between points in time and fossil species.

We need to continue fieldwork to identify more fossils and determine

how the species are related and how they lived.

Ultimately, everything is connected." The study, "Middle Miocene

Pierolapithecus provides a first glimpse into early hominid pelvic

morphology," will be published in an upcoming issue of the Journal of

Human Evolution.

The co-authors included David Alba from the Autonomous University of

Barcelona in Spain and the University of Turin in Italy, Sergio Almécija

from Stony Brook University in New York, and Salvador Moyà-Solà from the

Miquel Crusafont Institute of Catalan Palaeontology at Autonomous

University of Barcelona.

- ScienceDaily

|