The Buddha through modern literary eyes

By Prof. Sunanda Sugunasiri writing from Toronto

British author, Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses was regarded as

blasphemous and raised ire in the Islamic world. A fatwa condemning the

author to death was issued by the Iranian spiritual leader in 1989.The

furore brings to mind the treatment of the Buddha in two works of

fiction, one originally written by a Swiss writer and translated into

English, and the other in Sinhala in Sri Lanka.

There are both parallels and differences between Herman Hesse’s

ever-so-popular novel, Siddhartha, and Rushdie’s work. There are both parallels and differences between Herman Hesse’s

ever-so-popular novel, Siddhartha, and Rushdie’s work.

Both were written in a Western language and published in the West,

although Hesse was not born into the faith the book deals with.

Renunciation

If Prophet Mohammed is thinly veiled under the name of Mahamed,

Siddhartha is the lay name of the Buddha before his renunciation. The

Buddha himself becomes a fictional character at the hands of Hesse.

Indeed, the cover of the first English translation of Siddhartha in 1951

shows a seated Buddha.

Hesse’s character, however, does not match the life of historical

Siddhartha in all its detail. Our protagonist, for example, ends up as a

ferryman and not a Buddha. But there is little doubt that Hesse had the

Buddha’s life in mind when he developed his character.

Born to a Kshatriya family (the Buddha was born a prince), Siddhartha

leaves home “to join the ascetics,” and goes from teacher to teacher.

Dissatisfied, he goes on a solitary search.

All this is the life of the Buddha. Even the ferryman is symbolic of

the Buddha, the one who found the way to help sentient beings across the

ocean of life.

Twist of history

In a clever twist of history, Hesse takes Siddhartha, and his

companion Govinda, to the Buddha as his last teacher. Leaving the

Buddha, Siddhartha goes on the solitary search, just like the historical

Siddhartha did, vowing “I’ll conquer myself.”

This search, however, takes him on a different course from the

historical Siddhartha: to a courtesan who he asks to be his “friend and

teacher.” But this again is clearly not created out of the blue by the

author, but drawn upon the character of courtesan Ambapali who goes on

to become an Arahant under the Buddha.

In the course of the psychological transformation from spiritual

seeker to prisoner of the senses, Hesse uses the same dream technique as

the one that has stirred up the Rushdie controversy:

During the night ... Siddhartha had a dream. He dreamt that Govinda

stood before him, in the yellow robe of an ascetic ... He embraced

Govinda ... and kissed him. He was no longer Govinda, but a woman, and

out of the woman’s gown emerged a full breast, and Siddhartha lay there

and drank; sweet and strong tasted the milk from her breast. It tasted

of woman and man ... (Siddhartha, 1951, p. 50).

According to the Abhidhamma analysis of a human being, there is both

a woman and a man (yes, listed in that order) in each of us. While

elements like the senses – eye, ear, nose, tongue and body, are the

universals, ‘femininity’ and ‘masculinity’ are particulars. While each

of us come to be of a dominance of one or the other of the latter at

conception, the one not opted for remains dormant within us

nevertheless. Indeed it may be reflective of this that in the Sinhala

Buddhist culture, the Buddha comes to be called both ‘mother’ (of

nectar) (amaa maeniyan) and ‘father’ (budu piyaanan). Formally speaking,

if the former refers to the affective, i.e., the feeling domain of the

right brain hemisphere, the latter refers to the cognitive, i.e., the

rational domain of the left hemisphere.

This scene, as well as the lengthy encounter with the courtesan

(covering a full quarter of the novel), who finds herself with child,

can be seen as drawing upon Prince Siddhartha’s own lay life of

twenty-nine years. He lived in a royal household, entertained by wine

and dancing women. He had a wife and a son.

Hesse’s portrayal of Siddhartha, no doubt, is an extension of

historical Siddhartha’s life up to renunciation, but incorporating

significant elements of life after renunciation.

And he is clearly exploring the human side of the pre-Buddha, through

thinly veiled fictional detours.

Just as clearly, all this is offensive to the sensibility of the

Buddhist who likes to think of only the Buddha, as the one beyond a

shadow of lust, and in complete control of the senses, with the

pre-Buddha, the very anti-thesis, and preferred to be kept far off from

memory.

Despite the liberties taken of the type that would raise the ire of

the devout, Hesse departs from Rushdie in one significant way. He does

not treat the Buddha irreverently. Indeed, the protagonist addresses the

Buddha as, “O Perfect One.”

Yet, Siddhartha challenges him:

You show the world as a complete, unbroken chain ... linked together

by cause and effect. ... But ... this unity and logical consequence of

all things is broken in one place. Through a small gap there streams

into the world of unity something strange, something ... that cannot be

demonstrated and proved; that is your doctrine of rising above the

world, of salvation (p. 35).

Siddhartha is challenging here one of the Buddha’s most fundamental

teachings: Nibbana. The entirety of his teachings thus comes tumbling

down. The Buddha is no longer the Perfect One!

Or the All-knowing One, as known to millions of followers. The Buddha

responds to the challenge with the words, “You have found a flaw.”

Now the Buddha admits to his fallibility!

The Buddha even wishes the departing young Siddhartha well in his

search.

Sensibility

Wouldn’t all this step on the Buddhist sensibility? A redeeming

factor for Hesse is that such a freedom is allowed by the Buddha

himself. In his Discourse to the Kalamas, the Buddha says: “... it is

proper that you have a doubt.” The Buddha cautions further not to accept

anything, even in the faith that “this is our teacher,” but only upon

personal experience.

Today, after over six decades, Siddhartha still adorns the shelves of

libraries and university course outlines in both the Western and the

Buddhist world. But what about when it first hit the bookstores?

As I recollect it, the publication hardly moved a feather in the

Buddhist world. Buddhist countries like Sri Lanka, Burma and Thailand

were just beginning to enjoy political freedom. The literary elite had

had their own education and training in the West, and were perhaps too

benumbed to the local culture. For the more sensitive, Siddhartha would

have been simply a twitch of the decadent West, and something to be

ignored!

Where Siddhartha found ready acceptance, of course, was among the

North Americans whose search for an alternative lifestyle ended in the

hippie culture.

A closer parallel to the Rushdie furore, however, is the Sinhala

novel written in the early seventies by Sri Lanka’s foremost writer of

the time, Martin Wickramasinghe. Bava taranaya (Crossing the Ocean of

Life) is the very story of the life of the Buddha.

While Wickramasinghe, born and raised a Buddhist, handles the Buddha

story fictionally with the same respect that Hesse does, his imagination

runs riot in one scene, which cuts to the very core of the Sinhala

Buddhist sensibility.

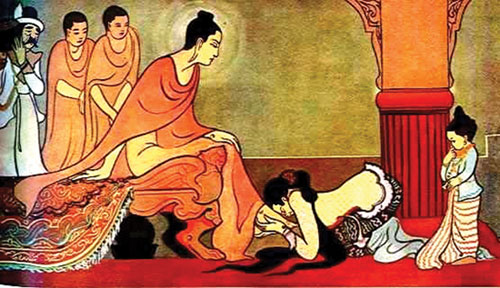

As in history, the Buddha in Wickramasingha’s novel (1973) returns to

his hometown. Here, he is venerated by his father, nursing mother and

the royal retinue with deep respect, but keeping their distance.

Now without waiting for Yasodhara, his former wife, to come to him,

the Buddha goes in search of her, and meets her in the bed chamber. And

here the reader is treated to the following moving scene:

Restraint

It was with the greatest restraint that Yasodhara held in check any

verbal expression of the surge of happiness that arose in her heart upon

seeing the Buddha. But the surge held in check was so overwhelming that

it knocked her right down. Soon up on her knees, she embraced the

Buddha’s feet, kissing them, as tears rolled down. As if in a stupor,

she then reached up the legs to just below the knees and started kissing

them. When King Suddhodana tried to remove her, the Buddha stopped him,

signalling with his right hand . Now Yasodhara gave vent to her love,

sorrow and happiness, turning them into a stream of tears. Seeing the

bed chamber and the contents therein that ushered in flashes of his lay

life from winning Yasodhara’s love through a skilful display of the

martial arts to the time of the birth of Rahula, the Buddha entered into

a Samadhi. Across his face spread an aura of Metta and Karuna. An

immediately sensing Yasodhara stopped kissing his legs and gazed at the

Buddha’s face. Even as her heart came to be overwhelmed with a happiness

at seeing the face in its lustre of spiritual happiness, she was given

to a fear (Bava taranaya, 13th printing 2008, p. 175,).

Clergy

If my memory serves me right, critics, journalists and the

intelligentsia, and most understandably the Buddhist clergy, were

outraged. And there were calls to ban the book, and pull it off the

racks of bookstores and university libraries. But luckily no effigy

burnings or death threats!

Luckily again Sri Lanka was no theocratic state. The multifaith

secular government let the matter lie where it should: in the hands of

the literary world.

Perhaps my literal translation does not capture all the nuances

intended by the author, but what does the literary world see in this

classic and powerful portrayal of conflict, denouement and resolution in

one single paragraph? I’d say a deft literary hand at work, inviting the

reader to at least six of the nine literary ‘tastes’ as in Bharata

Muni’s Natyasastra, depending on what the reader brings to it. First,

for the uninitiated and the immature reader, it is the srangaara rasa

(love), while for the conservative and traditional reader, it is raudra

(anger). There is also the karuna (compassion) for the helpless

Yasodhara, but also the compassion and the empathy of the Buddha himself

who, just prior to this scene, goes to where Yasodhara is, without

waiting for her to come to meet her. There is also the ‘apprehensive’

taste (bhaya) as Yasodhara ends given to a fear. But in the end, it is

the saanta rasa (peace), a Buddhism-inspired sensibility, that wins the

day, along with again karuna (compassion).

In the scene, the Buddha is portrayed as the Arahant with the kilesa

defilements jettisoned, and Yasodhara as the woman in samsara, in the

unsurprising vise grip of sentiment and feeling, and dukkha suffering.

Putting the book aside, the student of Buddhism is treated to a sixth

taste: heroic and energetic (utsaaha), reminiscing the story of the

Buddha leaving the household life, subjecting himself to self-torture to

the point of death and then experiencing the Awakening. And happily, it

is the same sentiment of energetic effort that comes to be associated

with Yasodhara who eventually becomes Arahant Bhaddhà Kaccànà, and

identified by the Buddha as being ‘foremost among those who quickly

attain direct knowledge’.

In the end, critical dialogue prevailed. Today, as then, I presume,

bava taranaya adorns the bookshelves and course lists of universities

and high schools.

Author Wickramasinghe, too, died the same way he lived – respected as

a provocative but mature novelist, a scholar of Buddhism and Sinhala

Buddhist culture, and, most importantly, a humanist. On a personal note,

as a budding literary buff, I was happy to have had the pleasure of

benefiting from all this, taking many a walk with him in the

neighbourhood of his Nawala, Rajagiriya home. And I still treasure on my

bookshelf the many books given to me, with his signature signature!

But why go to Switzerland or Sri Lanka to see how the Buddha has

taken kickings and beatings with a smile? A Zen master titles his work,

Dropping Ashes on the Buddha.

Closer to home, in a restaurant lobby in Toronto, a pot-belly

laughing Buddha invites you to a soup named after him!

The last time I tasted it, I thought Perfection had found a home in

the hands of the Chef!

Poet and short fiction writer, Prof. Sugunasiri is a Fulbright

Scholar in Linguistics at the University of Pennsylvania, USA, his

current research area is Buddhism. |