|

Strategy to disarm the virus: New hope for a universal dengue

vaccine

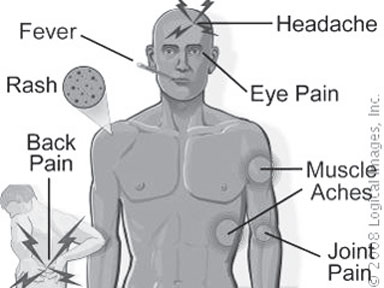

A new strategy that cripples the ability of the dengue virus to

escape the host immune system has been discovered by A STAR's Singapore

Immunology Network (SIgN). This breakthrough strategy opens a door of

hope to what may become the world's first universal dengue vaccine

candidate that can give full protection from all four serotypes of the

dreadful virus.

Early studies have shown that a sufficiently weakened virus that is

still strong enough to generate protective immune response offers the

best hope for an effective vaccine. However, over the years of vaccine

development, scientists have learnt that the path to finding a virus of

appropriate strength is fraught with challenges. This hurdle is

compounded by the complexity of the dengue virus. Even though there are

only four different serotypes, the fairly high rates of mutation means

the virus evolve constantly, and this contributes to the great diversity

of the dengue viruses circulating globally. Early studies have shown that a sufficiently weakened virus that is

still strong enough to generate protective immune response offers the

best hope for an effective vaccine. However, over the years of vaccine

development, scientists have learnt that the path to finding a virus of

appropriate strength is fraught with challenges. This hurdle is

compounded by the complexity of the dengue virus. Even though there are

only four different serotypes, the fairly high rates of mutation means

the virus evolve constantly, and this contributes to the great diversity

of the dengue viruses circulating globally.

In some cases, the immune response developed following infection by

one of the four dengue viruses appears to increase the risk of severe

dengue when the same individual is infected with any of the remaining

three viruses.

With nearly half the world's population at risk of dengue infection

and an estimated 400 million people getting infected each year[2], the

need for a safe and long-lasting vaccine has never been greater.

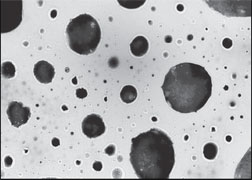

The new strategy uncovered in this study overcomes the prevailing

challenges of vaccine development by tackling the virus’ ability to

‘hide’ from the host immune system. Dengue virus requires the enzyme

called Mtase (also known as 2'-O-methyltransferase) to chemically modify

its genetic material to escape detection. In this study, the researchers

discovered that by introducing a genetic mutation to deactivate the

MTase enzyme of the virus, initial cells infected by the weakened MTase

mutant virus is immediately recognised as foreign. As a result, the

desired outcome of a strong protective immune response is triggered yet

at the same time the mutant virus hardly has a chance to spread in the

host.

Animal models immunised with the weakened MTase mutant virus were

fully protected from a challenge with the normal dengue virus. The

researchers went on to demonstrate that the MTase mutant dengue virus

cannot infect Aedes mosquitoes. This means that the mutated virus is

unable to replicate in the mosquito, and will not be able to spread

through mosquitoes into our natural environment. Taken together, the

results confirmed that Mtase mutant dengue virus is potentially a safe

vaccine approach for developing a universal dengue vaccine that protects

from all four serotypes.

The team leader, Dr Katja Fink from SIgN said, “There is still no

clinically approved vaccine or specific treatment available for dengue,

so we are very encouraged by the positive results with this novel

vaccine strategy.

Our next step will be to work on a vaccine formulation that will

confer full protection from all four serotypes with a single injection.

If this proves to be safe in humans, it can be a major breakthrough for

the dengue vaccine field.”

Associate Prof Leo Yee Sin, who heads the Singapore STOP Dengue

Translational and Clinical Research (TCR) Program said, “We are into the

seventh decade of dengue vaccine development, this indeed is an exciting

breakthrough that brings us a step closer to an effective vaccine.”

Associate Professor Laurent Rénia said, “Dengue is a major public

health problem in many of the tropical countries. We are very delighted

that our collaborative efforts with colleagues in Singapore and China

have made a promising step towards a cost-effective and safe dengue

vaccine to combat the growing threat of dengue worldwide.”

The Singapore Immunology Network (SIgN), officially inaugurated on

January 15, 2008, is a research consortium under the Agency for Science,

Technology and Research (A*STAR)'s Biomedical Research Council.

The mandate of SIgN is to advance human immunology research and

participate in international efforts to combat major health problems.

Since its launch, SIgN has grown rapidly and currently includes 250

scientists from 26 different countries around the world working under 28

renowned principal investigators.

Through this, SIgN aims at building a strong platform in basic human

immunology research for better translation of research findings into

clinical applications.

SIgN also sets out to establish productive links with local and

international institutions, and encourage the exchange of ideas and

expertise between academic, industrial and clinical partners and thus

contribute to a vibrant research environment in Singapore.

MNT

A well-connected core brain network helps humans to adapt

One thing that sets humans apart from other animals is our ability to

intelligently and rapidly adapt to a wide variety of new challenges -

using skills learned in much different contexts to inform and guide the

handling of any new task at hand.

Now, research from Washington University in St. Louis offers new and

compelling evidence that a well-connected core brain network based in

the lateral prefrontal cortex and the posterior parietal cortex - parts

of the brain most changed evolutionarily since our common ancestor with

chimpanzees - contains “flexible hubs” that coordinate the brain's

responses to novel cognitive challenges.

Acting as a central switching station for cognitive processing, this

fronto-parietal brain network funnels incoming task instructions to

those brain regions most adept at handling the cognitive task at hand,

coordinating the transfer of information among processing brain regions

to facilitate the rapid learning of new skills, the study finds. Acting as a central switching station for cognitive processing, this

fronto-parietal brain network funnels incoming task instructions to

those brain regions most adept at handling the cognitive task at hand,

coordinating the transfer of information among processing brain regions

to facilitate the rapid learning of new skills, the study finds.

“Flexible hubs are brain regions that coordinate activity throughout

the brain to implement tasks - like a large Internet traffic router,”

suggests Michael Cole, lead author of the study.

“Like an Internet router, flexible hubs shift which networks they

communicate with based on instructions for the task at hand and can do

so even for tasks never performed before,” he adds.

Decades of brain research has built a consensus understanding of the

brain as an interconnected network of as many as 300 distinct regional

brain structures, each with its own specialised cognitive functions.

Binding these processing areas together is a web of about a dozen

major networks, each serving as the brain's means for implementing

distinct task functions - i.e. auditory, visual, tactile, memory,

attention and motor processes. It was already known that fronto-parietal

brain regions form a network that is most active during novel or

non-routine tasks, but it was unknown how this network's activity might

help implement tasks.

This study proposes and provides strong evidence for a “flexible hub”

theory of brain function in which the fronto-parietal network is

composed of flexible hubs that help to organise and coordinate

processing among the other specialised networks.

This study provides strong support for the flexible hub theory in two

key areas.

First, the study yielded new evidence that when novel tasks are

processed flexible hubs within the fronto-parietal network make

multiple, rapidly shifting connections with specialised processing areas

scattered throughout the brain.

Second, by closely analysing activity patterns as the flexible hubs

connect with various brain regions during the processing of specific

tasks, researchers determined that these connection patterns include

telltale characteristics that can be decoded and used to identify which

specific task is being implemented by the brain.

These unique patterns of connection - like the distinct strand

patterns of a spider web - appear to be the brain's mechanism for the

coding and transfer of specific processing skills, the study suggests.

By tracking where and when these unique connection patterns occur in

the brain, researchers were able to document flexible hubs’ role in

shifting previously learned and practised problem-solving skills and

protocols to novel task performance. Known as compositional coding, the

process allows skills learned in one context to be re-packaged and

re-used in other applications, thus shortening the learning curve for

novel tasks.

What's more, by tracking the testing performance of individual study

participants, the team demonstrated that the transfer of these

processing skills helped participants speed their mastery of novel

tasks, essentially using previously practised processing tricks to get

up to speed much more quickly for similar challenges in a novel setting.

“The flexible hub theory suggests this is possible because flexible hubs

build up a repertoire of task component connectivity patterns that are

highly practiced and can be reused in novel combinations in situations

requiring high adaptivity,” Cole explains.

“It's as if a conductor practised short sound sequences with each

section of an orchestra separately, then on the day of the performance

began gesturing to some sections to play back what they learned,

creating a new song that has never been played or heard before.”

By improving our understanding of cognitive processes behind the

brain's handling of novel situations, the flexible hub theory may one

day help us improve the way we respond to the challenges of everyday

life, such as when learning to use new technology, Cole suggests.

“Additionally, there is evidence building that flexible hubs in the

fronto-parietal network are compromised for individuals suffering from a

variety of mental disorders, reducing the ability to effectively

self-regulate and thereforeexacerbating symptoms,” he says.

Future research may provide the means to enhance flexible hubs in

ways that would allow people to increase self-regulation and reduce

symptoms in a variety of mental disorders, such as depression,

schizophrenia and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

- MNT

Cancer cells change while moving throughout body

For the majority of cancer patients, it's not the primary tumour;

that is deadly, but the spread or “metastasis” of cancer cells from the

primary tumour to secondary locations throughout the body that is the

problem. That's why a major focus of contemporary cancer research is how

to stop or fight metastasis.

Previous lab studies suggest that metastasising cancer cells undergo

a major molecular change when they leave the primary tumour - a process

called epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). As the cells travel

from one site to another, they pick up new characteristics. More

importantly, they develop a resistance to chemotherapy that is effective

on the primary tumour. But confirmation of the EMT process has only

taken place in test tubes or in animals.

In a study, in the Journal of Ovarian Research, Georgia Tech

scientists have direct evidence that EMT takes place in humans, at least

in ovarian cancer patients. The findings suggest that doctors should

treat patients with a combination of drugs: those that kill cancer cells

in primary tumours and drugs that target the unique characteristics of

cancer cells spreading through the body. In a study, in the Journal of Ovarian Research, Georgia Tech

scientists have direct evidence that EMT takes place in humans, at least

in ovarian cancer patients. The findings suggest that doctors should

treat patients with a combination of drugs: those that kill cancer cells

in primary tumours and drugs that target the unique characteristics of

cancer cells spreading through the body.

The researchers looked at matching ovarian and abdominal cancerous

tissues in seven patients. Pathologically, the cells looked exactly the

same, implying that they simply fell off the primary tumour and spread

to the secondary site with no changes. But on the molecular level, the

cells were very different. Those in the metastatic site displayed

genetic signatures consistent with EMT. The scientists didn't see the

process take place, but they know it happened.

“It's like noticing that a piece of cake has gone missing from your

kitchen and you turn to see your daughter with chocolate on her face,”

said John McDonald, lead investigator on the project. “You didn't see

her eat the cake, but the evidence is overwhelming. The gene expression

patterns of the metastatic cancers displayed gene expression profiles

that unambiguously identified them as having gone through EMT.”

The EMT process is an essential component of embryonic development

and allows for reduced cell adhesiveness and increased cell movement.

According to Benedict Benigno, director of gynaecological oncology at

Atlanta's Northside Hospital, “These results clearly indicate that

metastasising ovarian cancer cells are very different from those

comprising the primary tumour and will likely require new types of

chemotherapy if we are going to improve the outcome of these patients.”

Ovarian cancer is the most malignant of all gynaecological cancers

and responsible for more than 14,000 deaths annually in the United

States alone. It often reveals no early symptoms and isn't typically

diagnosed until after it spreads.

“Our team is hopeful that, because of the new findings, the

substantial body of knowledge that has already been acquired on how to

block EMT and reduce metastasis in experimental models may now begin to

be applied to humans,” said Loukia Lili, co-author of the study.

- MNT

Seeking a clinical test for breast cancer

An international scientific collaborative led by the Harvard Stem

Cell Institute's Kornelia Polyak, MD, PhD, has discovered why women who

give birth in their early twenties are less likely to eventually develop

breast cancer than women who don't, triggering a search for a way to

confer this protective state on all women.

The researchers now are in the process of testing p27, a mammary

gland progenitor marker, in the tissue of thousands of women collected

over a 20-year period - women whose histories have been followed

extremely closely - to see if it is an accurate breast cancer predictor

in a large population of women. If the hypothesis is confirmed, likely

within a few months, Polyak says the commercial development of a

clinical test for breast cancer risk would follow. The researchers now are in the process of testing p27, a mammary

gland progenitor marker, in the tissue of thousands of women collected

over a 20-year period - women whose histories have been followed

extremely closely - to see if it is an accurate breast cancer predictor

in a large population of women. If the hypothesis is confirmed, likely

within a few months, Polyak says the commercial development of a

clinical test for breast cancer risk would follow.

In a paper in Cell Stem Cell, the researchers describe how a

full-term pregnancy in a woman's early twenties reduces the relative

number and proliferative capacity of mammary gland progenitors - cells

that have the ability to divide into milk-producing cells – making them

less likely to acquire mutations that lead to cancer.

By comparing numerous breast tissue samples, the scientists found

that women at high risk for breast cancer, such as those who inherit a

mutated BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene, have higher-than-average numbers of mammary

gland progenitors. In general, women who carried a child to full term

had the lowest populations of mammary gland progenitors, even when

compared to cancer-free women who had never been pregnant. In addition,

in woman who gave birth relatively early, but later still developed

breast cancer, the number of mammary gland progenitors were again

observed to be higher than average.

“The reason we are excited about this research is that we can use a

progenitor cell census to determine who's at particularly high risk for

breast cancer,” said Polyak, a Harvard Stem Cell Institute Principal

Faculty member and Harvard Medical School professor at the Dana-Farber

Cancer Institute. “We could use this strategy to decrease cancer risk

because we know what regulates the proliferation of these cells and we

could deplete them from the breast.”

Research shows that two trends are contributing to an increase in the

number of breast cancer diagnoses - a rise in obesity and the

ever-increasing number of women postponing child bearing. The

scientists’ long-range goal is to develop a protective treatment that

would mimic the protective effects of early child bearing. The research,

which took five years to complete, began with conversations between

Polyak and John Hopkins University School of Medicine Professor

Saraswati Sukumar.

The two scientists formed collaborations with clinicians at cancer

centres that see large numbers of high-risk women in order to obtain

breast tissue samples. They also worked with genomics experts and

bioinformaticians to analyse gene expression in different breast cell

types. At times, Polyak and Sukumar had trouble convincing others to

help with the study, which is unique in the breast cancer field for its

focus on risk prediction and prevention.

“In general people who study cancer always want to focus on treating

the cancer but in reality, preventing cancer can have the biggest impact

on cancer-associated morbidity and mortality,” Polyak said. “I think the

mentality has to change because breast cancer affects so many women, and

even though many of them are not dying of breast cancer, there's a

significant personal and societal burden.”

- MNT

Obese mothers' children ‘more likely to die young’

Children born to obese mothers are 35 percent more likely to die

before they reach 55, a study has found.

They also have a 29 percent increased chance of being admitted to

hospital for heart attacks, angina and stroke than those born to mothers

of a normal weight. Experts analysed data for 37,709 babies delivered

between 1950 and 1976 in Scotland. Their mother’s weight was recorded

during her first antenatal appointment in pregnancy.

The results showed that offspring were 35 percent more likely to have

suffered an early death by the age of 55 if their mother had been obese

in pregnancy (body mass index of 30 or over). This held true even after

other factors, including mother’s age, socio-economic status, sex of the

child and current weight, were taken into account. Writing in the

British Medical Journal , the experts concluded: “Maternal obesity is

associated with an increased risk of premature death in adult

offspring.” Among the 28,540 mothers, 21 percent (5,993) were overweight

and four percent (1,141) were obese.The researchers, from the

universities of Aberdeen and Edinburgh, said the results were a “major

public health concern”, especially seeing as only four percent of

mothers in the study were obese, “far smaller than current levels in the

US and UK”.

- The Independent

|