|

Review

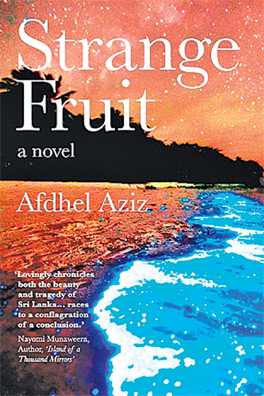

A fruitful strangeness

by Dilshan Boange

There is a certain sumptuousness in Strange Fruit by Afdhel Aziz,

which is not necessarily flavourful as bearing a sensuous vivacity upon

the reader’s palette.

What one finds is an assortment of many threads that weave together a

stream of emotions that deal with different states of mind and body, and

soul, in different settings of geography, and tonalities that speak of

textural richness in story structure with epigraphy from song and poetry

that add depth to better gauge characters that simply refuse to stay one

dimensional.

As one turns pages one sees how the principal characters crafted by

Aziz, realise that the worlds they inhabit, like them, do not stay

static. The strangeness encountered by the characters of Maya and Malick

in each other is an alluring and endearing one. As one turns pages one sees how the principal characters crafted by

Aziz, realise that the worlds they inhabit, like them, do not stay

static. The strangeness encountered by the characters of Maya and Malick

in each other is an alluring and endearing one.

Therefore, it is that very strangeness that turns fruitful for them.

There is sorrow and bitterness, romance and beguiling landscapes,

heartache and anxiety, hidden frustrations and lustful allure.

There are also silences, working as inertia of the hapless, and the

wordless quiet shared between lovers. Sri Lanka is a land of countless

emotions. We are a people in that sense who defy one dimensionality.

That plethoric variety is a symbolic sumptuousness.

Epic

Strange Fruit isn’t a sweeping epic of a romance saga, nor is it a

stringently ideologically pinned book that banks completely on the

separatist war episode and the 1983 July riots to be the sole driving

force to capture its readership.

What the author has designed, it appears, is to depict a story about

characters who aren’t as adults in the folds of the ‘average Sri

Lankan’, whose lives unfolded in a period that was inescapably affected

by the horrors of suicide bombers in Colombo, civil riots and also

jungle warfare.

The life of the character of ‘Soldier boy’ too happens in the same

country that the central characters Maya and Malick find their romance

blooms, but the urban lovers and the soldier of rural roots are worlds

apart.

But this is a story of our generation, and I feel the Sri Lankan

children of the next decade may find this past depicted in Strange Fruit

very much estranged from their world of experience.

With each passing generation the voices of the previous era get

entrenched more firmly in the firmament of advancing society’s

‘imagination’, and will be more readily read as ‘fiction’.

Perhaps that is the beauty of what literature is destined to be in

its relation to the past, as ‘stories’ with manifold facets.

Being a child of the 80s and 90s myself whose childhood wasn’t

‘wired’ to the ‘cyber age’, I couldn’t help but relate to the nostalgic

tones the book carries in relation to the Colombo centric urban

landscape before the 21st century arrived.

It is an era that marked a turning point in the pace and pulse of a

people. And one that children of this decade will never relate to.

Not in the city, not in the villages, because the era of internet and

cell phones, and its gamut of digital dynamism has pervaded from coast

to coast. The world Aziz unfolds in Strange Fruit is thus a world to be

found only in the memories of those who actually lived those times.

Perhaps in this sense Aziz sought to create a narrative that records an

era that shaped his days of boyhood, which of course sadly has faded

into the ‘past’. This is very much a novel that moves with the

generation whose ‘impressionable age’ was in the previous century.

July riots

Like Maya who migrated as a result of the July riots of ’83 who finds

her home estranged, perhaps the author Aziz now living in New York, may

be subconsciously dealing with the possibility of gradual strangeness

that will face him from his beloved homeland since with each passing day

Sri Lanka changes and any Sri Lankan living overseas on return is bound

to feel some sense of change that left him or her behind.

|

Afdhel Aziz |

And like Malick whose very being is bound to his lifestyle in Sri

Lanka, Aziz too possibly feels that his inner pulse speaks of being Sri

Lankan more than anything else.

Perhaps in this vein the characters of Malick and Maya carry facets

of the author himself. I couldn’t help but feel the subtext of the novel

may be woven with tones of those emotional concerns of the author

himself.

After all the story unfolds to be a labour of some considerable

emotional investment on the part of the author.

The texture of the novel has a notable element of music woven in it.

The epigraphy which adorns the beginning of each chapter says that

different tonalities have given shape to what the author feels

exemplifies the essences in the story as it progresses in segments.

The variety in the epigraphs is remarkable. As I was reaching the end

of the book I found playing in my head the track ‘Make it with you’ sung

by British pop band ‘Let Loose’, who sang it as a cover of the original

song by the band ‘Bread’.

Although the lyrics of that song were not in the text, my experience

of reading the book shows there is a strong element of music bound to

the bones of this story.

One must also take note of the fact that the novel’s title was also

inspired by the doleful song of the same by Billie Holiday. Music

defines Malick in many ways and so to give context about how he is also

perceived culturally may be pertinent to cite the following line–“His

love for Sri Lanka was bone-deep; where he was from was an inherent part

of who he was.”

Fusion

Like vignettes the life of Maya and Malick unfold with snapshot

discursive at times which perhaps symbolically may be seen as something

of a jazzy motif.

I will state for the record that I have no expertise in musicology

but the observations one can make in this regard is how the fusion of

moments may show a sense of weaving fragments together to create a

larger picture almost in the light of a collage.

Although one of the most demonstrative examples I can think of in

this regard would be Michael Ondaatje’s Coming Through Slaughter,

Strange Fruit while certainly being worlds apart from the aforementioned

novel of Ondaatje in both narrative structure and story theme, still has

an approach of in certain respects which appears to build on the ‘fusion

of moments’ to show a progression of the lives of the lovers Maya and

Malick.

In Chapter 4 through the vignette titled, ‘Between two worlds’, the

reader finds what is a counterpoint to the common belief ‘English is

empowerment’ in the context of language politics in Sri Lanka.

Identity

Maya who grapples with the unsettledness of a hybrid identity finds

an agonising truth which perhaps some foreign visitors to our country,

or a Sri Lankan who had lived overseas for a considerable time and

developed the noticeable ‘expat veneer’, is likely to encounter, which

is that in certain contexts not being proficient in Sinhala like the

average Sri Lankan can be critically disempowering.

At the heart of this novel is an introspective investigation through

the characters of Maya and Malick over what matters to a person to call

a place ‘home’. Even the character of ‘Soldier boy’ finds the ‘tour of

duty’ creates change in him to an extent that his familiar home environs

seem estranged to his psychology.

Maya and Malick find that in each other’s love they find a meaningful

‘home’ which transcends definitions of geography and national cultures.

If one takes on something of a more academically inclined critical

incision at the text of the novel related to how Sinhala words have been

incorporated to an English prose narrative, one will notice how Sinhala

words have been elucidated in the narrative itself through description.

To every Sri Lankan, words like kottu and kasippu are explanations by

themselves.

I certainly do not intend to make a complete list of the words from

the Sinhala language that have found their way into Strange Fruit to be

listed out in this review but I cannot help but raise the question as

which readership Aziz intends the book to ‘speak out to’ exactly?

While there are some marked elements in the novel that lend to make

Sri Lanka ‘exotic’ which are also I must say done tastefully to

tantalise the unacquainted with our tropical emerald isle, some of those

facets mentioned may lend to making the narrative voice seem somewhat

even distanced from the landscape it seeks to bring to life convincingly

to the reader.

Dialect

In this sense I wonder whether it is a distant overseas gazer’s pulse

that wove in a ‘distanced’ note or two to the tone of the narrative with

regard to the aspects aforementioned.

A glossary of terms can serve a reader unfamiliar with whatever words

of a local language or dialect that finds voice in a story set in a

setting not familiar to the reader. It is somewhat a noticeable practice

among novelists.

Prose that carry description of the irregularly occurring non-English

word either preceding or succeeding the placement of the non-English

word, in my opinion, tends to disrupt the tones of familiarity between

the text and the reader, if the reader is one who is of the culture that

is sought to be portrayed by the text.

If anyone cares to consider as food for thought, the intrigue sparks

in the reader unfamiliar with the non-English words will create a desire

to get better perspective of it through reference to a glossary in the

novel with lexical definitions and even descriptions with context of the

non English words and readers of that nature may even be persuaded

(depending on the prowess of the writer who crafted the narrative) to do

further research about what is represented by those non-English terms in

this day and age where Google can guide you to nearly anything explained

under the sun!

Investigating themes such as ‘homeland’ and ‘identity’ the question

of ‘patriotism’ is also raised in the novel, with something of a

resolution to that burning question found in Chapter 10.

If patriotism is epitomised through self sacrifice to what end should

the ultimate sacrifice of one’s life be made? Without giving way too

much for the benefit of those who have not yet read the book, let me

simply offer this excerpt: “He wasn’t a patriot in the sense that he

died for his country. But he died for something. Someone. Strangers,

actually.’ ‘Maybe that’s a better definition of a patriot,’ said Maya.

‘Someone who dies for strangers.’ ”

Maya as a returnee to her estranged ‘homeland’ is stung by the

question of ‘what is home’ much more sharply when she finds her love for

Malick compelling her to accept that unlike her, Malick’s conception of

home collides with hers.

“‘This is where you grew up. This is your home. But it’s not mine,”

says Maya to Malick at the point where it seems decisive that they must

pragmatically approach what future their relationship has in the wake of

choosing what kind of life together is or isn’t possible for them.

It is interesting to see how Aziz draws on that age-old saying ‘home

is where the heart is’ which has a simple yet indelible truth and

beauty, as he charts the direction of the story’s end. Every love story

has its share of laughter and tears. And every love story has its share

of partings.

But how exactly do these partings work for Malick and Maya? This

article is only a review, not a detailed synopsis, nor the story itself. |