Extreme inequality

The massive concentration of economic resources in the hands of a few

people presents a significant threat to democracy and well-being. Mark

Goldring, Chief Executive of Oxfam GB, calls for a more progressive

agenda for the redistribution of wealth.

|

|

Extreme wealth inequality

is not good for society |

In January 2014 Oxfam revealed that the richest 85 people in the

world had the same amount of wealth as the bottom half of the world's

population: over three billion people. This attracted global media

interest.

As usual, our claim was challenged, but not in the usual way. When

Forbes magazine updated the data just a few months later, they found

that we were wrong. It now took just the richest 69 people to equal the

wealth of the poorest half!

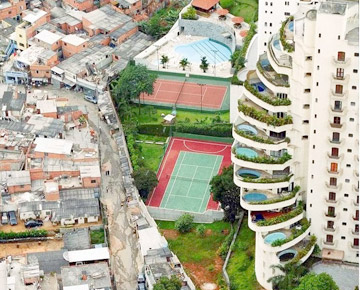

The disparities between the rich and the poor are increasing. Just a

few feet of wall in Rio separates the have-nots living in slums from the

have-it-alls in the penthouse apartments next door. In the UK, newspaper

articles on bankers' billions sit alongside those documenting the rising

number of people forced to rely on food banks.

Does this really matter? Some say that economic growth benefits and

creates opportunities for all and that this must involve some getting

richer than others; that attacking the very rich is an ideological

position that helps no one.

Oxfam's interest is not about the rights and wrongs of wealth per se.

It is about the fact that extreme inequality of wealth leads to extreme

inequalities in all forms of power, policy and well-being, so that poor

people do not benefit from improved health, education or opportunity,

even in an economy that seems to be growing.

Over the last year there has been widespread recognition that

increasing inequality of income and wealth cannot go on unabated.

President Obama promised in his State of the Union address to tackle

inequality of opportunity. Pope Francis tweeted to warn that inequality

is "the root of social evil".

Even the global institutions with orthodox economic outlooks -

including the IMF and the World Bank - have been warning of the dangers

of inequality, and, in the case of the IMF's Christine Lagarde, quoting

Oxfam.

Leaders and institutions are beginning to challenge inequality

head-on and people are paying attention to this debate. Not only was

Thomas Piketty's book Capital in the Twenty-first Century, about the

link between rising inequality and wealth, a massive publishing success,

but it also sparked a flood of soul-searching about the state of modern

capitalism. That an economics tome of graphs and data can top

best-seller lists on both sides of the Atlantic clearly demonstrates the

resonance of this issue.Why does this matter for development and

well-being?

Over the past two decades we have seen impressive reductions in

poverty and improvements in health, education and other key indicators

in many of the poorest countries around the world.

The rapid economic growth of emerging economies has seen many

countries improve their prospects dramatically. While this is hugely

encouraging, looking through the lens of simple averages masks the

unequal fate of those left behind.

A baby born into a rich family in prospering Nigeria will live a

longer life with far greater opportunities than a baby born into a poor

family. Gender inequalities will exacerbate these discrepancies even

further, with a boy likely to spend more than 10 years in school,

compared to the three years of schooling that a girl can expect.

These disparities are not just a phenomenon in developing countries.

Here in the UK a child born in leafy Richmond, South West London can

expect to live 15 years longer than one born in Tower Hamlets in the

east of the city. That is a year of extra life for every mile covered as

you travel across London.

- Third World

Network Features |