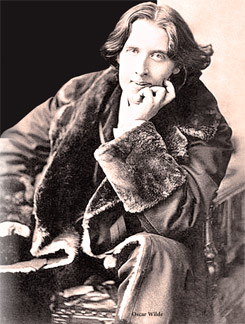

The importance of being Wilde

by L. Umagiliya

Oscar Wilde, had he been alive today would be 160 years old on

October 16. But, as ill luck would have it, Wilde died quite young at an

age when many begin life. He was a victim of the society which bore him,

worshipped him and then censured him.

|

Oscar Wilde |

Wilde talked brilliantly of the family (can we forget Mrs. Cheveley

in ‘An Ideal Husband?’ but he himself was no family person. Indeed he

and his wife knew it three years after their marriage. This is of course

not to say that he did not love his wife or family. He idolised children

(himself having two of

his own). He adored pretty women (Constance Wilde was exquisitely

pretty) but Wilde never loved women, at least, not in any physical

sense.

Charming

There lives a charming story of Wilde’s visit to a Dieppe brothel

soon after he was released from the confines of Reading gaol. Typical of

the man was the reply when asked of the experience. “It was the first in

these ten years, and it will be the last. It was like cold mutton”.

Wilde remained homosexual in his habits for the rest of his life.

Oscar Wilde was born in Ireland on October 16, 1854. His father,

William Wilde was in many ways the greatest of English – speaking ear

surgeons.

It has been said that Oscar Wilde’s mother, anxious to have a

daughter was so deeply depressed when a second son was born, that she

dressed Oscar as a girl long after the age when the clothes of male and

female children became distinctive.

And that, in some funny way known to psychology but obscure to

commonsense, this fashion gravely affected his sexual nature. Oscar’s

sister was born three years after him and presumably his mother’s desire

for a daughter was appeased before Oscar was of an impressionable

dressing age.

Gold medal

In October 1871, at 17 Wilde received a scholarship from Portora and

won an entrance scholarship to Trinity College, Dublin which he freely

acknowledged were the happiest years of his life ‘thus far’. Here he was

to win the Berkely gold medal for Greek. It proved to be his most useful

and expensive academic distinction, for he often pawned it when hard up.

Academic honours are normally won by grinding or a good memory, not by

genius and young Wilde was no different. He was a monstrously lazy

student who hated hard work but possessed a prodigious memory and could

not help remembering every word he read.

In October 1874, Wilde went to Oxford. His life there was

unimpressive apart from his winning in his field every conceivable prize

on offer. Occasionally working, he took a first class in Modern Classics

in the Honours school, and in 1878, a first in the Honours Finals, and

both were regarded by his examiners as the most brilliant of their

respective years.

His dislike for sports, in fact for anything outdoor cricket, rowing

– overrode his dislike for students. He took no part in physical

exercise, or could he work up the least interest in games, then or

thereafter. Never did Oxford University throw up a less typical Oxonian

than Oscar Wilde.

Prowess

Wilde was an enormous man – well over six feet and his hatred for

sports was more the pity, for well could he hold his own against almost

anybody.

There lives a story of Oscar’s prowess and strength which went round

Oxford like wildfire. Wilde was afraid of no man physically or

intellectually.

But even in those days at Oxford, there was something odd about this

young man’s formal appearance – his long, rich brown hair, big

colourless face, full thick sensuous lips, magnificent eyes and bold,

checked suits.

Though not effeminate, people found something distinctly strange

about Wilde. A further tale went something like this. The Junior Common

room of Magdalen decided one day that the time had come to beat up this

odd fellow – this insipid poseur.

An advance guard of four heroes burst into Wilde’s room. The first

intruder flew outside with the aid of Wilde’s boot, the second got a

punch that doubled him up, the third made his return journey through the

air and the fourth, a beefy fellow of Wilde’s height and weight was

carried by Wilde to his room (as a nurse carries a baby) and buried

beneath a pile of clothes. That was the first and last attempt to rag

Wilde. Wilde’s basic nature was to be generous. He was the kindest of

souls and he was generous to a fault. There were many friends who

sponged on him.

Any hard luck story would find him groping in his pocket and

generally not for loose change. He lived by his thoughts.

“Those who have much are always greedy, those who have little always

share”. His own impulse whether rich or poor (and often he was both) was

always to share. His natural kindness and his love for others made him

many friends at Oxford.

Young Wilde

Oxford life pleasant though it may have been for the young Wilde, we

must swiftly leave. And we return, to find Oscar, rehearsing another

kind of role. For Wilde always was the actor, playing the part of life

to its utmost.

The rules were his and no one else could convince him of any other.

Half of Wilde – the emotional half – never developed beyong adolescence,

while the other half – the intellectual half – was well developed.

Thus we shall always see him as an exceptionally brilliant

undergraduate, halfboy, half genius, the boy in Oscar showing his

constant need for showing off while the man in him was sometimes amused

and often bored.

And this we see well in “to get into the best society nowadays” he

was to say “one has either to feed people, amuse people or shock people

– That is all”, and once again - “to be in society is a bore, but to be

out of it is a tragedy.”

Wilde was never happy unless acting a part or dressing – up or

startling people by some form of attire or shocking behaviour. And

through the parts he played, his love of acting and masquerading, he

irritated the hypocritical moral turpitude of Victorian society to which

he had the distinct misfortune to be born into.

Court case

But perhaps what we mostly remember Wilde for is his sordid court

case (contrary to popular belief it was for procuring he was found

guilty, and was acquitted of the charge of debauching youth and

corrupting innocence) to one observer in court that day.

Intellectually speaking Wilde stood head and shoulders above the

judge who tried him and the counsel who prosecuted him. “While another

likened him” to a wounded lion being worried by a pack of nangrei dogs.

Every civilised being now agrees that the environment of the day made a

grave error in prosecuting Oscar Wilde at all.

It was a witch hunt and Victoria’s Government went after its pound of

flesh with a vengeance. For Wilde lived at a time when virtue and

hypocrisy walked the land. The Victorians knew better than any previous

age how to “Compound sins they were inclined to...” or “By damming those

they had no mind to...”

Pound of flesh

And so as the Victorians collected their pounds of flesh it was the

end of Oscar two years in prison had nearly finished him. He went into

obscurity to Paris and to the arms of the too few friends he now had. He

wrote nothing of worth, perhaps only the masterful ‘Ballad of Reading

Gaol’ relating his experiences in prison. It was moving and it was

profound as only Wilde could tell...

‘I walked with other souls in pain, within another ring’.

And was wondering if the man had done,’

A great or little thing, When a voice behind me whisperd low’

That fellow’s got to swing,’

Yet each man kills the thing he loves,’

By each let this be heard,’

Some with a flattering word the coward does it with a kiss,’

The brave man with a sword “For each man kills the thing he loves”.

Wilde died in Paris in 1900 in an obscure tardy little hotel sprawled

on a dirty little bed watched over by the innkeeper who had befriended

him in his final hour.

Oscar Wilde was born too early and too young for a society which saw

in this brilliant young man nothing but ridicule. |