Nightmare at the Picasso Museum

The greatest museum of Picasso's works has been engulfed by scandal

and crisis. Closed for the past five years, it is finally ready to

reopen its doors to the public. But has the bitter struggle for

Picasso's legacy been resolved?

|

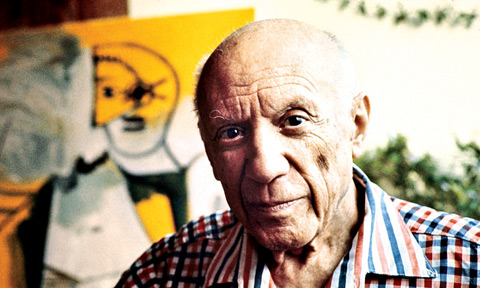

Pablo Picasso |

On June 30, 1972 Pablo Picasso created his last self-portrait. He had

depicted himself many times before, but never like this. His face looked

like a skull with stubble. Its colour was greenish-grey.

The mouth was a straight slit. Only the lines under his eyes proved

his features were flesh and not raw bone, which seems to protrude from

his head at the left of the picture, where it is set against red fire,

blood, or a setting sun.

From his youthful self-portraits to his bare-chested appearance, at

the age of 75, in Henri-Georges Clouzot's 1956 film The Mystery of

Picasso, the artist, so fit and long-lived, enjoyed showing off his

muscular body. But in his last images of himself, the shoulders that

were still so powerful when he displayed them in Clouzot's adoring film

had shrunk to the dried flatness of a mummy.

Pride of place

This was his 91st year. Picasso looked at himself without illusions,

underlining the true state of things with heavy black lines.

When friends came to visit he would show them the self-portrait of

June 30. It had pride of place on an easel apart from his routine

clutter. He wanted to know how others saw it.

Picasso habitually studied his own works in this meditative way: his

studio, and all his homes, were filled with his own artworks, going

right back to juvenilia from his teenage years in Spain.

He kept a bank vault in Paris, filled with paintings, prints,

sculptures, and even poetry. But his self-portrait as a death's head was

something else; he kept goading friends to interpret it, insisting they

gaze with him into its big terrifying eyes. This picture of a death

foreseen was, for Picasso, "a mirror", his friend and biographer John

Richardson told me.

Less than a year after making it, he died, at home in Mougins in the

south of France, on 8 April 1973.

Advertisement

He was buried at the foot of Mont Sainte-Victoire in Provence, in a

striking final homage to Cézanne - whose hesitant, searching paintings

of this mountain did so much to inspire Picasso's cubist revolution in

the early years of the 20th century.

He was survived by his second wife, Jacqueline, as well as his

"legitimate" son by his first marriage, Paulo, and Paulo's three

children, Pablito, Marina and Bernard.

Then there was his former lover Marie-Thérèse Walter and their

daughter Maya. And Françoise Gilot, the author of Life with Picasso, a

merciless picture of an ageing artist lording it over his much younger

lover, rich with embarrassing details of his habits and opinions - such

as his insistence that one cannot be a real woman without becoming a

mother.

After failing to prevent its publication in 1964, Picasso tried to

cut their children, Paloma and Claude, out of his life.

He also left 1,876 paintings, 1,335 sculptures, 7,089 standalone

drawings, 18,000 prints, 2,880 ceramic pieces and 149 notebooks of

drawings. It was the greatest collection of Picasso's art in either

private or public hands.

After his death, the vast personal collection that was discovered in

his various studios and homes befuddled even his closest friends and

most intimate students. No one had known the scale and substance of this

private dimension to Picasso's genius. It was not just the stupefying

quantity of works he kept, but how and why he kept them, which had no

equivalent in art.

Legacy

The collection that Picasso left came to about 70,000 items. But it

took nearly a decade to sort out his legacy. First, the rights of his

children and grandchildren had to be established - hardly a simple

matter.

Picasso loved fatherhood, as his portraits of his children

demonstrate, but he performed its duties inconsistently.

As the diverse and fragmented Picasso family tried to settle the

estate, they suffered a series of misfortunes that still offer the

darkest possible material to those who see the painter of Guernica as a

misogynist who ruined the lives of his wives, mistresses, children and

even grandchildren.

His grandson Pablito died from drinking bleach a few days after being

refused admittance to Picasso's funeral by his second wife, Jacqueline,

who kept out everyone but herself and his eldest son.

Pablito's father Paulo died in 1975, after a life wrecked by alcohol.

Marie-Thérèse Walter, the lover whose opulent body is the theme of some

of his wildest art, hanged herself in 1977. Nearly a decade later, in

1986, Jacqueline herself committed suicide.

Even in his lifetime, Picasso saw his private life become

unpleasantly public. It is sometimes implied his lovers were passive

victims of his demanding, even childish character but more than one of

them got her own back in print.

Fernande Olivier, the lover of Picasso's youthful days in Montmartre,

was first to publish in 1930. Gilot caused even more of a sensation with

her revelations.

In 2001, Marina Picasso, Paulo's daughter, published a book accusing

her grandfather of damaging her childhood, first by crushing her

father's character, and then by refusing adequate financial help to a

family he knew to be struggling.

Out of the infernal soap opera of the Picasso family in the 1970s,

Claude Picasso, the painter's only surviving son, emerged as the leader

of the family and took a highly influential role in shaping Picasso's

artistic legacy.

To be continued |