A myth-maker at work

Reviewed by Kalakeerthi Dr. Edwin Ariyadasa

“People don't go to the North Pole to fall off icebergs. They go to

offices, quarrel with their wives and eat cabbage soup.”

Anton Chekhov (1860-1904)

Human history is replete with a hefty plethora of myths, legends,

fairytales, fables and other creations of a lush creative imagination.

In the dim past, during the dawn of humanity, the early men and women

gave uninhibited rein to their thoughts to roam wherever they wished.

The outcome of this unrestricted flight of early human inventiveness

is the vast treasuretrove of Babylonian, Egyptian, Greek, Roman,

Chinese, Indian and other traditions of story-telling, that the modern

man has become the heir to.

The Babylonian epic poem - Gilgamesh of the third millennium BC. is

an outstanding product of the myth-making skills of the ancients. The Babylonian epic poem - Gilgamesh of the third millennium BC. is

an outstanding product of the myth-making skills of the ancients.

Masses adored the myths and legends imputing to them a sacred and

holy aura. Most of the stories had to do with gods and their divine

prowess. The alluring mystery they exuded appealed to the people.

But, with the passage of time, literacy tastes underwent a massive

transformation. Scientific thinking progressed in leaps and bounds.

Advanced technologies of communication made literature available to the

masses at large. The preoccupation with miracles, magic, mystery and

myth began to wane.

They needed realism. Literature, the masses felt, should celebrate

the matter-of-fact.

The staple idiom of the fiction of the modern era became the

conjugation of the routine affairs of life. If a touch of mystery was

added to this formula, it happened only very rarely indeed.

But, sensitive writers of the age of advanced technologies of

sophisticated communication, felt a yearning to seek the unexpected and

the mysterious, in a world propelled by computers that were mechanically

logical. The throbbing of the heart had to relieve the regular, precise

ticking of the digital.

In Sri Lanka, there was hardly any effort by creative men and women,

to try and leaven the troubling monotony of a routine – driven society.

Fiction

Our literary works, especially the field of fiction, seemed to lack a

pioneering spirit that would instil this enlivening dimension of

phantasy and the mysterious to the realm of creativity.

But currently, a person of exceptional creativity has appeared, armed

with an anthology of stones, in the urgently needed genre of fantasy.

And, what really matters is that the works in this collection do not

have even the least trace of the amateurish.

They display a highly skilled narrative expertise and an all-round

competence.

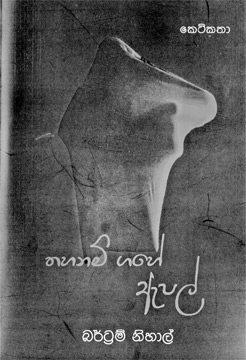

The anthology is titled Tahanamgahe Apple (Apples from the forbidden

tree). The myth-making author is Bertram Nihal. Without any attempt

whatsoever at overstatement, I can forthrightly aver, that the ten

stories in the publication represent a flawless instance of creative

story-telling. The language level, the measured tempo of the narrative

progress and the predominant style, cumulatively contribute to the

overall impact of the stories. The initial tale titled Vinodapala is

built on the character of an itinerant entertainer who arrives at a

remote village bearing a strange gift.

He has brought along a magic box. Clad in the motley of a jester, he

displays the visuals of sacred sites to the devoted, unsophisticated

rural folk. Soon the box gets transformed into an instrument of power

and eventually, the literate itinerant vendor of entertainment evolves

into a powerful leader. While underlining the irony of the emergence of

power, the story-line hints at a mystery which is surprisingly resolved

at the finale, adding a deeper dimension to the impact of the story.

The last in the series of ten stories in the work is an undoubted

classic in twisted humour and mind-boggling mystery.

The work titled Miniha Vehunu Yaka (The devil possessed by a man)

turns the usual phenomenon wittily on its head. What generally happens

in this kind of story is a “Devil possessing a man”. Here the process is

the other way about.

Nuances

The exceptionally ironical nuances of the story begin to come through

overwhelmingly when the man who possess the devil turns out to be a

politician.

The total series has been conceived with admirable care and

discipline.

The shock-effect of the stories is very cleverly manipulated by the

writer, leading the reader to an unexpectedly strange realm of literary

appreciation.

In the story titled Nasaraniya the cultural character is a young man

affected by a freak state of mind. The title implies “good-for-nothing.”

The efficacy of the writer's literary craftsmanship is vividly

exhibited by the hypnotic allure he imparts to each story. Once you make

your entry into his story-domain, you are helplessly caught up and you

go along with its flow, hardly aware that you are so absolutely

absorbed.

His Wavullu (The bats) is a work that grips the totality of the

reader's being by transporting him into a region that is inexplicably

beyond any logic. The vast horde of bats that taken over a human

settlement seems the central idiom of a modern parable.

The work is so clearly exceptional and the effort is so admirably

erudite that those who are really keen about a truly creative

contribution of a new chapter to the continuing chronicle of Sri Lankan

fiction, should make an in-depth study of this really innovative

anthology of fiction.

Two elucidatory introductions enhance the value of this collection.

These are by the author Bertram Nihal and by literary critic M. Edwin

Pieris.

At this stage, while felicitating the author for an intellectually

satisfying creative banquet, I earnestly request the alert students of

modern Sinhala fiction to examine this work at seminar level.

The cover-art is an aesthetically advanced creative effort. The

resounding outcome of all this is that Bertram Nihal is making an

impressive debut as a pathfinder in modern Sinhala fiction. |