|

Navam Full Moon Poya Day is on Tuesday:

Leading a life without greed, aversion and delusion

By Lionel Wijesiri

It appears as if our actions - what we do, say or think - simply

arise and then disappear without any trace except for their visible or

physical impact on other people and the environment. However, according

to the Buddha, all motivated actions, done knowingly or unknowingly,

create potential results that correspond to the moral quality of those

actions.

|

|

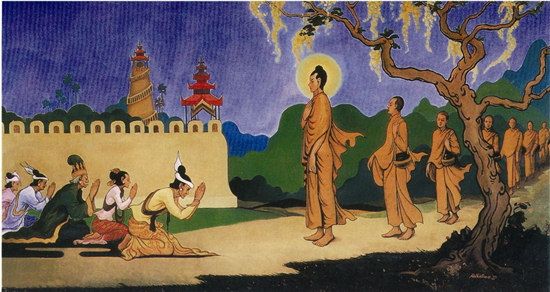

The Buddha visits Rajagaha

where King Bimbisara came to pay homage. (How an artist

visualised it) |

This potential of our deeds to produce morally appropriate results is

known as karma.

Karmic potentiality brings fruits, good and bad, corresponding to the

deeds previously done and one’s latent tendencies. Such fruits may occur

immediately after the act is done, that is, in this life itself, or in

the next life, or in some subsequent life, that is, as long as one

remains unawakened from the sleep of karmic life.

As long as we remain in samsara, our accumulated karma will be

capable of producing and reproducing fruits whenever the conditions are

right, and keep on transfiguring itself into more complicated karmic

forms.

In terms of moral quality, the Suttas - such as the Mula Sutta, [The

roots of moral actions] found in Anguttara Nikaya, distinguish karma

into two major categories: the unwholesome (akusala) and the wholesome (kusala).

Unwholesome karma is “action that is spiritually detrimental to the

agent, morally reprehensible, and potentially productive of an

unfortunate rebirth and painful results.”

Their unwholesomeness comes from their roots, from which arise

secondary defilements such as selfishness, gluttony, envy, anger, pride,

arrogance, laziness, prejudice, and forgetfulness, and from which more

defiled actions arise.

Mula Sutta

In the Mula Sutta, Buddha speaks about three roots of what is

unskillful. These three toots of evils are known in Pali as lobha, dosa,

moha.

Lobha is greed, desire, craving, attachment. The Visuddhimagga gives

the its definition as follows: Lobha has the characteristic of grasping

an object like “monkey lime”. Its function is sticking, like meat put in

a hot pan. It is manifested as not giving up, like the dye of

lamp-black.

Its proximate cause is seeing enjoyment in things that lead to

bondage. Swelling with the current of craving, it should be regarded as

taking (beings) with it to states of loss, as a swift-flowing river does

to the great ocean.

Lobha has the characteristic of grasping like monkey lime. Monkey

lime was used by hunters to catch monkeys. A hunter sets a trap of lime

for monkeys. Monkeys who are free from “folly and greed” do not get

trapped. But a greedy, foolish monkey comes up to the pitch and handles

it with one paw, and his paw sticks fast in it.

Then, thinking: I’ll free my paw, he seizes it with the other paw,

but that too sticks fast.

To free both paws he seizes them with one foot, and that too sticks

fast. To free both paws and the one foot, he lays hold of them with the

other foot, but that too sticks fast. To free both paws and both feet he

lays hold of them with his muzzle: but that too sticks fast. So that

monkey thus trapped in five ways lies down and howls, thus fallen on

misfortune.

Dosa means anger, hatred, ill will, aversion. In the Visuddhimagga.

dosa is defined as follows: It has flying into anger or churlishness as

characteristic, like a smitten snake; spreading of itself or writhing as

when poison takes effect, as function; or, burning that on which it

depends as function, like jungle-fire; offending or injuring as

manifestation, like a foe who has got his chance; having the grounds of

vexation as proximate cause, like urine mixed with poison.

In Theravada tradition, moha is considered to be synonymous with

avijja, but the terms are used in different contexts. Ignorance (avijja)

is actually identical in nature with the unwholesome root “delusion” (moha).

When the Buddha speaks in a psychological context about mental

factors, he generally means “delusion”; when he speaks about the causal

basis of samsara, he means “ignorance”. Thus, the term avijja is used

when identifying the first causal link in the twelve links of dependent

origination, and moha is used when discussing the mental factors.

Tanha

On a deeper psychological level, these unwholesome roots arise from

and are fed by the three kinds of desire, that is, the desire for

sense-pleasures (Kana tanha), for becoming this and that (bhava tanha),

or for getting rid of something (vibhava tanh?). The roots of each of

these desires are very deep and called latent tendencies (anusaya),

which are basically, lust (raga), ill will (vyapada), and ignorance (avijja).

When there is a strong desire for something we are deluded into

thinking that nothing else is important except that desirable object;

this is kama tanha, worked up by lust as the dominant latent tendency.

|

|

People who are easily

angered generally have what some psychologists call a low

tolerance for frustration |

As a result of this overpowering desire, we dislike thoughts or

objects that distract us from our quest; this is kama tanha working with

ill will. As a result of all this desiring and questing, we ignore

anything can really help us; this is the result of kama tanha rooted in

ignorance. Bhava tanha works in a similar way: when we want to become

something, be it making some money or attaining “eternal life,” the

latent tendencies of lust, ill will and ignorance work on our minds in

the same way; ignorance is the dominant latent tendency. So, too, in the

case of vibhava tanha, which arises when, for example, we think we have

failed in our quest for happiness; ill will is the dominant latent

tendency.

Removal

Today, in the 21st century, we see that the “intelligent” man, who

proudly believes himself to be a ‘free agent’ - the master of his life

and even of nature - is in his spiritually undeveloped state actually a

passive patient driven about by inner forces he does not recognise.

Pulled by his greed and pushed by his hatred, in his blindness he does

not see that the brakes for stopping these frantic movements are in his

reach, within his own heart.

One way of understanding the human mind is that its natural goodness

is often covered up by negative influences from outside and our

reactions to them, that is, the workings of lobha, dosa and moha tend to

prevent our natural tendency to do good.

The proper way to remove these unwholesome roots (at least

temporarily) is to carefully keep track of our mind. This mental

tracking is done in two ways that are mutually complementary: by calming

the mind and by insight.

By calming the mind, we clear away the unwholesome roots, and through

insight, we see directly into it, thus allowing their opposites,

generosity, loving kindness and wisdom, to arise.

For some, it is easier to cultivate insight first; for others,

calmness first. Either way, one helps to strengthen the other, so that

they work together like the two wings of a bird, lifting us above

unwholesome mental states.

In this way, we begin to have a right view of life, and are able to

understand and deal with suffering, so that we are in due course be

totally free from it. |