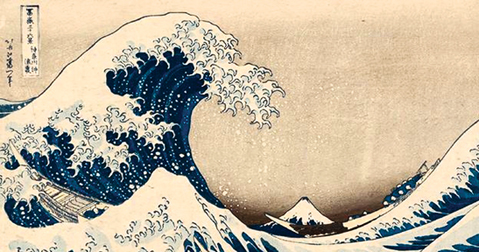

It all began with the wave

Hokusai's creation that swept the world :

Without the Japanese

printmaker Hokusai, Impressionism might never have happened. Jason

Farago examines the moment when European art started turning Japanese.

|

The wave (Credit: Katsushika Hokusai / Museum of Fine Arts,

Boston) |

In the beginning was the wave. The blue and white tsunami, ascending

from the left of the composition like a massive claw, descends

pitilessly on Mount Fuji - the most august mountain in Japan, turned in

Katsushika Hokusai's vision into a small and vulnerable hillock. Under

the Wave off Kanagawa, one of Hokusai's Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji,

has been an icon of Japan since the print was first struck in 1830-31,

yet it forms part of a complex global network of art, commerce, and

politics.

Its intense blue comes from Hokusai's pioneering use of

Prussian Blue ink - a foreign pigment, imported, probably via China,

from England or Germany. The wave, from the beginning, stretched beyond

Japan. Soon, it would crash over Europe.

Last month the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, home to the greatest

collection of Japanese art outside Japan, opened a giant retrospective

of the art of Hokusai, showcasing his indispensible woodblock prints of

the genre we call ukiyo-e, or 'images of the floating world'.

It was the second Hokusai retrospective in under a year; last autumn,

the wait to see the artist's two-part mega-show at the Grand Palais in

Paris stretched to two hours or more. American and French audiences

adore Hokusai - and have for centuries. He is, after all, not only one

of the great figures of Japanese art, but a father figure of much of

Western modernism. Without Hokusai, there might have been no

Impressionism - and the global art world we today take for granted might

look very different indeed.

Fine print

|

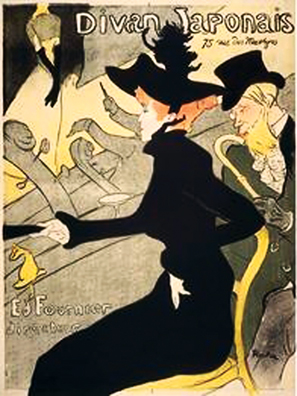

Toulouse-Lautrec embraced both Japanese art and printmaking,

as in his poster for the nightclub Le Divan

Japonais (Credit: Henri de Toulous |

Hokusai's prints didn't find their way to the West until after the

artist's death in 1849. During his lifetime Japan was still subject to

sakoku, the longstanding policy that forbade foreigners from entering

and Japanese from leaving, on penalty of death. But in the 1850s, with

the arrival of the 'black ships' of the American navy under Matthew

Perry, Japan gave up its isolationist policies - and officers and

diplomats, then artists and collectors, discovered Japanese woodblock

printing.

In Japan, Hokusai was seen as vulgar, beneath the consideration of

the imperial literati. In the West, his delineation of space with color

and line, rather than via one-point perspective, would have

revolutionary impact.

Both the style and the subject matter of ukiyo-e prints appealed to

young artists like Félix Bracquemond, one of the first French artists to

be seduced by Japan. Yet the Japanese prints traveling to the West in

the first years after Perry were contemporary artworks, rather than the

slightly earlier masterpieces of Hokusai, Hiroshige, and Utamaro.

Many of the prints that arrived were used as wrapping paper for

commercial goods. Everything changed on 1 April, 1867, when the

Exposition Universelle opened on the Champ de Mars, the massive Paris

marching grounds that now lies in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower. It

featured, for the first time, a Japanese pavilion - and its showcase of

ukiyo-e prints revealed the depth of Japanese printmaking to French

artists for the first time.

Claude Monet went, we know, and soon enough Monet had acquired 250

Japanese prints, including 23 by Hokusai, which covered the walls of his

house in Giverny in the north of France. Monet's series of grainstacks

and poplars, of Rouen Cathedral and Waterloo Bridge, owe a great deal to

Hokusai's earlier experiments of depicting a single subject over dozens

of images. The influence ran from Monet's art into his life. His wife

wore a kimono around the house.

His garden at Giverny is modelled directly after a Japanese print,

right down to the arcing bridge and bamboo.

|

The composition of Degas’ The Tub shows a heavy debt to

Japanese

printmaking (Credit: Edgar Degas/Musée d'Orsay, Paris) |

Other artists were influenced less by Hokusai's landscapes than by

his renderings of human forms. Edgar Degas, especially, found in

Hokusai's manga - his thousands of sketches of fish, sumo wrestlers,

geisha, and everyday city-dwellers - the inspiration for his drastic

depictions of women in fin-de-siècle Paris.

His dancers, backs curved and faces in profile, display some

characteristics of Japanese portraiture, but one sees the influence of

Hokusai especially in Degas's bathers: both artists were uncommonly

interested in women's private, rather than public, appearances.

Degas' pastel The Tub, from 1866 and now at the Musée d'Orsay, is a

proudly two-dimensional composition with heavy debts to ukiyo-e. And his

etching of Mary Cassatt at the Louvre quotes directly from Hokusai's

manga: Cassatt has shifted her weight to one leg, while the woman whose

pose she imitates is being dragged off by a wild horse.

That Degas etching reveals another influence of Hokusai and other

printmakers: they elevated the reputation of graphic arts in France, and

made printmaking into a more respectable medium for fine artists.

"Seriously, you must not miss it,"

Cassatt wrote to her fellow artist Berthe Morisot on the occasion of

a Japanese prints exhibition. "You

|

Hokusai’s Three Women Playing Instruments is a hanging

scroll, executed with ink on silk - (Credit: Katsushika

Hokusai / Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) |

who want to make colour prints, you couldn't imagine anything more

beautiful... You must see the Japanese - come as soon as you can." Her

modern printmaking coincided almost exactly with the arrival of Japanese

art in France, and no one embraced the two as passionately as Henri de

Toulouse-Lautrec. Though he started as a painter, Lautrec soon moved

almost exclusively to prints and posters.

His poster for the Divan Japonais, a Paris nightclub decorated with

bamboo and paper lanterns, shows the cancan dancer Jane Avril in severe,

Orientalised profile. Lautrec's fascination with ukiyo-e was social as

much as formal.

The large panels of solid colour that recur in Lautrec's prints and

posters derive from the example of Hokusai and other Japanese artists.

But just as much, ukiyo-e prints showed Lautrec that louche life -

teahouses, restaurants, brothels - could be the stuff of art.

Rising in the East

It's worth recalling that what brought Hokusai and other ukiyo-e

printmakers to the attention of Monet, Degas, Cassatt, and Lautrec were

trade deals, on uneven terms, between Japan and the West. France and

other industrial powers were thriving; Japan was in upheaval, as the

shogunate gave way to the Meiji Restoration.

So the exchange was uneven from the start, economically and

culturally as well. Japan, in the Japoniste imagination, was a country

preserved in amber - unchanged over its two-and-a-half centuries of

isolation. It was a place where daily life still had the beauty and the

purity that industrialisation had blasted from European society.

|

Monet drew inspiration from his Japanese garden at Giverny

for many of his famous late works (Credit: The Print

Collector/Getty Images)) |

Few western artists were interested in the full depth of Japanese art

- the monumental sculpture, the Chinese-influenced painting, the

Buddhist reliquaries. Their interest, rather, was more like that of the

American naval officer in Puccini's opera Madam Butterfly: in love with

a girl in Nagasaki, but never in doubt that he holds the power in their

unequal relationship.

By 1905, however, when the Imperial Army thumped to victory in the

Russo-Japanese War, that fantasy could no longer hold. The Japan of the

early 20th Century was a world power, a modern empire, and suddenly not

so easy to imagine as a fairy land of beautiful women in communion with

nature. Japan retained its aesthetic reputation for elegance, harmony,

and simplicity for Westerners of the early 20th Century - the architect

Frank Lloyd Wright, for one, was a huge Japanophile and a major ukiyo-e

collector.

But it is no coincidence that Picasso, Braque, Rousseau, and other

French artists who came of age after Japonisme turned to Africa (and to

a lesser extent Oceania) to fulfill their primitivist fantasies.

Breaking free of the rigours of Western representation, as the

Impressionists began to do and as the Cubists may indeed have required a

gaze onto worlds beyond Europe. But the one thing they could not stand

was when the people of those worlds gazed back.

-BBC Magazine

|