The secrets of the master forgers

Before anyone had heard of Michelangelo Buonarotti, the most valuable

sculptures on the Renaissance Italian art market were ancient Roman

marble statues. Several biographical accounts demonstrate that even an

artist as great as Michelangelo could be involved in wilful forgery,

setting out to create an ancient Roman marble of his own. It did nothing

to impede his reputation. Indeed, having successfully passed off his

work as a Roman marble helped add lustre to the start of a glistening

career, by showing Michelangelo had the technical skill and creative

genius to match his forebears.

| In his new book The Art

of Forgery, art historian Noah Charney explores how the best

forgers in the world managed to fool so many experts. Here,

he reveals how Michelangelo got away with it – and the

secrets of the garden shed forger. The ultimate master

forger? |

The first biography of Michelangelo, written by renowned historian

Paolo Giovio, describes the artist as having “great genius… in contrast

to a character so rude and savage as to make his private life one of

unbelievable pettiness”. Michelangelo carved the marble statue Sleeping

Eros in 1496, when he was only 21 and, according to Giovio, doctored it

in order to make it appear to be ancient.

The statue was passed off as such when it was sold to Cardinal

Raffaele Riario, grandnephew of Pope Sixtus IV and a great collector of

early Roman antiquities (who perhaps should have known better).

When Riario later found out that he had bought a forgery, he returned

the statue to the dealer from whom he had bought it, Baldassarre del

Milanese.

|

Credit Getty Images |

However, between Riario buying the work and realising he had been

duped, Michelangelo had gone from being an unknown 21-year-old to Rome’s

hottest commodity, thanks largely to the fame of his Pietà, which

proudly stood in the Basilica of Saint Peter’s in Rome. Del Milanese was

thus happy to take it back, and had no trouble selling it on, now under

the authorship of the suddenly famous Michelangelo.

Whether undertaken as a practical joke, to show that his work was as

good as that of the ancients or for reasons of more criminal intent,

Michelangelo’s deception does not seem to have angered the original

owner of the Sleeping Eros.

Cardinal Riario became Michelangelo’s first patron in Rome,

commissioning two other works in 1496 and 1497.

This is an early example of a recurring narrative: successfully

fooling those who consider themselves experts does not always cause rage

– it can also endear the forger to the expert.

That Riario bought the original Sleeping Eros believing it to be an

ancient Roman marble is not in question. But we cannot be sure of the

artist’s ultimate motivations, because various sixteenth-century

biographies shift the guilt of having concocted the deception between

Michelangelo and the slippery art dealer, Baldassarre del Milanese.

While Michelangelo’s possible complicity in a forgery scandal may be

surprising, the Sleeping Eros was not the only work he faked – far from

it.

The renowned biographer Giorgio Vasari noted that: “He also copied

drawings of the Old Masters so perfectly that his copies could not be

distinguished from the originals, since he smoked and tinted the paper

to give it an appearance of age. He was often able to keep the originals

and return his copies in their place.” Alas, no more is known of which

drawings were involved in this Renaissance bait-and-switch, but the

story provides insight into the mind of a great artist who was also, it

seems, a great forger and art thief, demonstrating how thin is the line

between artistic genius and criminality.

The garden shed forger

On 16 November 2007, the failed contemporary artist Shaun Greenhalgh

(born 1961) was convicted for a forgery scheme of unprecedented

diversity in the history of art crime. His octogenarian parents, Olive

and George, were likewise sentenced for their roles as frontmen in an

elaborate con to sell Shaun’s forged creations. The family produced more

than 120 fake artworks over 17 years, earning at least £825,000 and

fooling experts at such institutions as Christie’s, Sotheby’s and the

British Museum. Scotland Yard fears that more than 100 of their

forgeries are still out there, mislabelled as originals.

Most forgers specialise in creating works in the style of a single

artist or period. Greenhalgh produced everything from ‘ancient’ Egyptian

sculpture, an 18th-Century telescope and 19th-Century watercolours to a

mid-20th-Century Barbara Hepworth duck statue.

|

Clay tablet from Syria. Shaun Greenhalgh was caught after

misspelling words in cuneiform (Credit: The Art Archive/Alamy) |

The Greenhalghs were finally caught for a simple oversight: in

attempting to forge an ancient Assyrian relief sculpture, they

misspelled several words in cuneiform.

Shaun Greenhalgh was raised in an impoverished council estate in

Bolton in the UK.

Though he had no formal artistic training, his father George, a

technical drawing instructor, encouraged him in his desire to paint

professionally.

After galleries repeatedly rejected Shaun’s paintings, he developed a

grudge against the art world for failing to recognise his artistic

talents.

In order to allow Shaun to avenge himself against the art community –

and to supplement their meagre income – the Greenhalghs concocted a

plan.

They sold forgeries made by Shaun by way of a provenance trap. The

family would locate a slightly obscure catalogue from an old auction,

and select a lot that was described in vague terms, such as ‘antique

vase, possibly Roman’. Shaun would create a new artwork, artificially

aged, to match the existing provenance of the auction catalogue. Experts

would then be lured into ‘discovering’ the old provenance for the new

object before them.

The presence of the authentic provenance, and the enthusiasm of

having discovered the link, proved enough to convince experts of the

authenticity of Shaun’s fakes. It was the con that made the crime

successful, not Shaun’s artistic abilities. In Shaun’s own words, his

creations were simply “knocked up in the garden shed out back”.

The genius of the con lay in the performance of Shaun’s

wheelchair-bound father, George. In his guise as a loveable and charming

invalid, George would present the forged artwork to experts, claiming

that it had been in his family for generations.

George would never suggest what the object was, but he would leave a

hint as to where it came from – a clue that would lead the experts, hot

on the scent of a major discovery, to the real provenance.

The experts would be given space to reach their own conclusion: that

the object before them was the object referred to in the provenance,

which had until now been lost.

Family forger

The details of one of Shaun’s forgeries serve as example of the

family’s methods. A silver lanx, or decorative platter, dating back to

the ancient Roman occupation of Britain was found at Risley Park,

Derbyshire, in 1736. The ploughman who found the lanx had broken it up

and distributed the pieces as souvenirs among his fellow workers.

There has been no record of the Risley Park lanx since. In 1991 the

Greenhalghs offered a Roman silver lanx to the British Museum. They had

bought relatively inexpensive original Roman silver coins and smelted

them using a miniature furnace stored above their refrigerator. They

fused the lanx together, the solder lines visible, making it look as

though it was the complete reconstructed Risley Park lanx of William

Stuckeley’s description. The British Museum purchased it.

Other Greenhalgh forgeries included sculptures ‘by’ Constantin

Brancusi, Gauguin and Man Ray, busts of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson,

and paintings by Otto Dix, LS Lowry and Thomas Moran, whose work Shaun

boasted that he could ‘fire off in 30 minutes’.

His two most profitable creations were the Amarna Princess, a

20in-tall Egyptian calcite sculpture purported to be from 1350–1334 BC,

and Assyrian stone relief tablets (c. 700 BC). The Assyrian reliefs,

supposedly from Sennacherib’s palace in Mesopotamia, raised the first

suspicions about the family, leading to their eventual arrest.

|

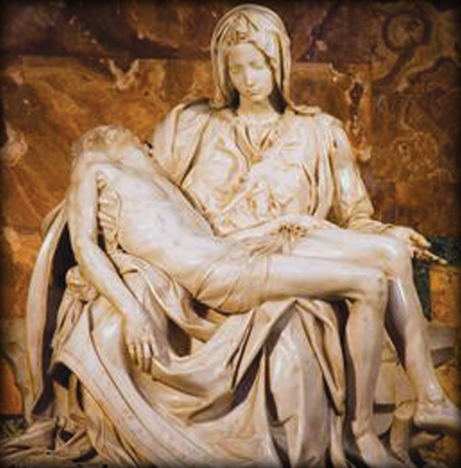

Michelangelo’s early forgeries were reassessed after he

created The Pietà between 1498 and 1499 (Credit: Peter

Barritt/Alamy) |

The misspelled words in cuneiform were noted by experts at the

British Museum, from whom the Greenhalghs had sought authentication.

The story of Shaun Greenhalgh and his family exemplifies the subject

of this chapter: forgers seek to fool the art community as revenge for

its having dismissed their own original creations.

As Detective Constable Ian Lawson of Scotland Yard said, “[Shaun]

thought he was having it over a lot of people that should have known

better.

It is more of a resentment of the art world, to prove that they could

do it.” Unlike so many forgers who seemed to enjoy their

post-incarceration celebrity, however, Shaun Greenhalgh refused to give

any interviews and avoided the spotlight after his release from prison

in 2011.

For those who feel alienated from the art world, Shaun is something

of a folk hero, showing up a community that many consider elitist and

undeserving of sympathy.

Profit was not the primary motivation for the family. Despite their

income, the Greenhalghs continued to live in relative poverty, rarely

spending any of their illicit earnings.

When asked by Vernon Rapley, the then-head of the Arts and Antiques

Unit, why they chose to live so modestly with so much money in the bank,

Shaun replied with candour, “I have five brand new pairs of socks in my

dresser.

What more could I want?” Shaun succeeded in showing the art world

that his skill, with the help of a provenance-trap con, surpassed their

connoisseurship.

(This is an extract

from Noah Charney’s recently published The Art of Forgery initially

featured in the BBC Magazine) |