Shockingly sinister

The all time favourites nursery rhymes may appear

innocuous, but their back stories are disturbingly dark writes Clemency

Burton-Hill:

Plague, medieval taxes, religious persecution, prostitution: these

are not exactly the topics that you expect to be immersed in as a new

parent. But probably right at this moment, mothers of small children

around the world are mindlessly singing along to seemingly innocuous

nursery rhymes that, if you dig a little deeper, reveal shockingly

sinister backstories. Babies falling from trees? Heads being chopped off

in central London? Animals being cooked alive? Since when were these

topics deemed appropriate to peddle to toddlers?

Since the 14th Century, actually. That’s when the earliest nursery

rhymes seem to date from, although the ‘golden age’ came later, in the

18th Century, when the canon of classics that we still hear today

emerged and flourished. The first nursery rhyme collection to be printed

was ‘Tommy Thumb’s Song Book’, around 1744; a century later Edward

Rimbault published a nursery rhymes collection, which was the first one

printed to include notated music –although a minor-key version of ‘Three

Blind Mice’ can be found in Thomas Ravenscroft’s folk-song compilation

Deuteromelia, dating from 1609.

|

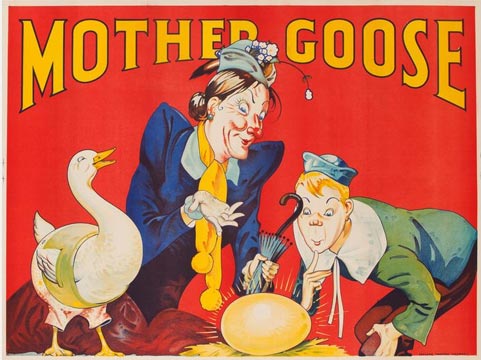

Many nursery rhymes appear in books attributed to the

fictional ‘Mother Goose’, who was first mentioned in a fairy

tale book published by Charles Perrault in 1695 (Credit:

Corbis) |

The roots probably go back even further. There is no human culture

that has not invented some form of rhyming ditties for its children. The

distinctive sing-song metre, tonality and rhythm that characterises

‘motherese’ has a proven evolutionary value and is reflected in the very

nature of nursery rhymes. According to child development experts Sue

Palmer and Ros Bayley, nursery rhymes with music significantly aid a

child’s mental development and spatial reasoning. Seth Lerer, dean of

arts and humanities at the University California – San Diego, has also

emphasised the ability of nursery rhymes to foster emotional connections

and cultivate language.

“It is a way of completing the world through rhyme,” he said in an

interview on the website of NBC’s Today show last year. “When we sing

[them], we’re participating in something that bonds parent and child.”

Vintage nursery

So when modern parents expose their kids to vintage nursery rhymes

they’re engaging with a centuries-old tradition that, on the surface at

least, is not only harmless, but potentially beneficial.

But what about those twisted lyrics and dark back stories? To unpick

the meanings behind the rhymes is to be thrust into a world not of sweet

princesses and cute animals but of messy clerical politics, religious

violence, sex, illness, murder, spies, traitors and the supernatural.

A random sample of 10 popular nursery rhymes shows this.

‘Baa Baa Black Sheep’ is about the medieval wool tax, imposed in the

13th Century by King Edward I. Under the new rules, a third of the cost

of a sack of wool went to him, another went to the church and the last

to the farmer. (In the original version, nothing was therefore left for

the little shepherd boy who lives down the lane). Black sheep were also

considered bad luck because their fleeces, unable to be dyed, were less

lucrative for the farmer.

The stuff of nightmares

‘Ring a Ring o Roses’, or ‘Ring Around the Rosie’, may be about the

1665 Great Plague of London: the ‘rosie’ being the malodorous rash that

developed on the skin of bubonic plague sufferers, the stench of which

then needed concealing with a ‘pocket full of posies’. The bubonic

plague killed 15% of Britain’s population, hence ‘atishoo, atishoo, we

all fall down (dead)’.

‘Rock-a-bye Baby’ refers to events preceding the Glorious Revolution.

The baby in question is supposed to be the son of King James II of

England, but was widely believed to be another man’s child, smuggled

into the birthing room to ensure a Roman Catholic heir. The rhyme is

laced with connotation: the ‘wind’ may be the Protestant forces blowing

in from the Netherlands; the doomed ‘cradle’ the royal House of Stuart.

The earliest recorded version of the words in print contained the

ominous footnote: “This may serve as a warning to the Proud and

Ambitious, who climb so high that they generally fall at last”.

‘Mary, Mary Quite Contrary’ may be about Bloody Mary, daughter of

King Henry VIII and concerns the torture and murder of Protestants.

Queen Mary was a staunch Catholic and her ‘garden’ here is an allusion

to the graveyards which were filling with Protestant martyrs. The

‘silver bells’ were thumbscrews; while ‘cockleshells’ are believed to be

instruments of torture which were attached to male genitals.

‘Goosey Goosey Gander’ is another tale of religious persecution but

from the other side: it reflects a time when Catholic priests would have

to say their forbidden Latin-based prayers in secret – even in the

privacy of their own home.

‘Ladybird, Ladybird’ is also about 16th Century Catholics in

Protestant England and the priests who were burned at the stake for

their beliefs.

‘Lucy Locket’ is about a famous spat between two legendary 18th

Century prostitutes.

‘Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush’ originated, according to

historian RS Duncan, at Wakefield Prison in England, where female

inmates had to exercise around a mulberry tree in the prison yard.

Not safe for children?

‘Oranges and Lemons’ follows a condemned man en route to his

execution – “Here comes a chopper / To chop off your head!” – past a

slew of famous London churches: St Clemens, St Martins, Old Bailey, Bow,

Stepney, and Shoreditch.

‘Pop Goes The Weasel’ is an apparently nonsensical rhyme that, upon

subsequent inspection, reveals itself to in fact be about poverty,

pawnbroking, the minimum wage – and hitting the Eagle Tavern on London’s

City Road.

In our own sanitised times, the idea of presenting these gritty

themes specifically to an infant audience seems bizarre. It outraged the

Victorians, too, who founded the British Society for Nursery Rhyme

Reform and took great pains to clean up the canon. According to Random

House’s Max Minckler, as late as 1941 the Society was condemning 100 of

the most common nursery rhymes, including ‘Humpty Dumpty’ and ‘Three

Blind Mice’, for “harbouring unsavoury elements”.

The long list of sins, he notes, included “referencing poverty,

scorning prayer, and ridiculing the blind… It also included: 21 cases of

death (notably choking, decapitation, hanging, devouring, shrivelling

and squeezing); 12 cases of torment to animals; and 1 case each of

consuming human flesh, body snatching, and ‘the desire to have one’s own

limb severed’.”

Dark origin

“A lot of children’s literature has a very dark origin,” explained

Lerer to Today.com.

“Nursery rhymes are part of long-standing traditions of parody and a

popular political resistance to high culture and royalty.” Indeed, in a

time when to caricature royalty or politicians was punishable by death,

nursery rhymes proved a potent way to smuggle in coded or thinly veiled

messages in the guise of children’s entertainment.

In largely illiterate societies, the catchy sing-song melodies helped

people remember the stories and, crucially, pass them on to the next

generation. Whatever else they may be, nursery rhymes are a triumph of

the power of oral history. And the children merrily singing them to this

day remain oblivious to the meanings contained within.

“The innocent tunes do draw attention away from what’s going on in

the rhyme; for example the drowned cat in Ding dong bell, or the grisly

end of the frog and mouse in A frog he would a-wooing go”, music

historian Jeremy Barlow, a specialist in early English popular music,

tells me. “Some of the shorter rhymes, particularly those with nonsense

or repetitive words, attract small children even without the tunes. They

like the sound and rhythm of the words; of course the tune enhances that

attraction, so that the words and the tune then become inseparable.” He

adds, “The result can be more than the sum of the parts.”

(This story is a part of BBC Britain – a new series

focused on exploring the extraordinary island, one story at a time)

|