Can good journalism outlive newspapers?

by Nalaka Gunawardene

|

|

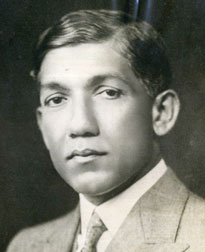

Media mogul D.R.

Wijewardene |

Adapted from the writer’s remarks made at the D. R. Wijewardene

commemorative event held on 26 February 2016 at the Lakshman Kadirgamar

Institute, Colombo

Can newspapers survive the challenge from digital and online media?

Plenty of printer’s ink has been spent reflecting on this question.

There are no easy answers, and perhaps we also need to rephrase the

question.

I begin by declaring a bias: I am rather partial to paper and ink. I

grew up reading newspapers from the age of five, and for several years

in my early career, I made a modest living working for an English

language newspaper.

Many like me, of a certain age and above, seem to have a nostalgic

attachment to newspapers. One key question for the print industry:

Beyond tapping such sentimental appeal (which diminishes over time), can

newspapers stay relevant and viable? How can they adapt and evolve to

keep serving the public interest?

History is not always a reliable guide, but in this instance, it may

well be.

|

|

The author and the

panellists at the D.R. Wijewardene Commemorative event |

The modern mass media in Sri Lanka has a history of just under two

centuries. If we don’t count the government gazette, which was started

by the British rulers in 1802, our newspaper history can be traced back

to Colombo Journal.

Old tensions

That biweekly newspaper first appeared in January 1832 – but folded

up at the end of the following year. It has been openly critical of the

colonial authorities in London, who ‘asked’ it to be shut down. (So the

tension between government and the press is as old as newspapers!).

But that void was soon filled by many and varied titles – including

The Observer and Commercial Advertiser, which started in 1834. It has

had many incarnations and continues today as the Sunday Observer.

Local language newspapers took a bit longer to appear, but eventually

claimed much larger market shares. The first Tamil newspaper Udaya

Tharakai was published from Jaffna in 1841, and the first Sinhala

newspaper Lankalokaya from Galle in 1860. Interestingly, our media

industry at the beginning was not as Colombo-centred as it is now.

From the outset, survival has always been a struggle for most of our

newspapers. According to the scholar monk Kalukondayawe Pannasekera’s

voluminous history of Lankan newspapers, we have had hundreds of

newspaper titles that never marked even their first birthday. Few lived

to reach a double digit age.

First Press baron

Those that survived did so because they combined good editorial

content with sound business management and were sustained by innovation.

Keeping up with the changing times – in terms of society, market and

politics – is the biggest challenge for any newspaper, then and now.

Indeed, these qualities contributed to the phenomenal success of D.

R. Wijewardene, our first Press Baron. About a century ago, he laid the

foundation for his publishing house (Associated Newspapers of Ceylon

Limited) by acquiring struggling titles – Dinamina (in 1914), and the

Ceylonese (relaunched as Ceylon Daily News in 1918). He added the Ceylon

Observer to his growing stable in 1923.

Wijewardene had more capital, imagination and tenacity than did the

original founders of those newspapers. He innovated at every stage of

newspaper production. It covered the reliable news and sound opinions,

bold use of images, clever advertising strategies and an efficient

distribution network.

H. A. J. Hulugalle’s biography, The Life and Times of D. R.

Wijewardene, offers a fascinating account of the man and his times. This

book, first published in 1960 and still in print, must become

recommended reading for every newspaper editor and manager concerned

with the future of their industry.

It is instructive to ask ourselves: What would D. R. Wijewardene do,

if he were alive today, to respond to a totally different world?

For this, we need to look at what drove the Cambridge-educated lawyer

to become a newspaper publisher.

According to Hulugalle, he was driven by a vision based on a simple

premise: The value of a well-informed public opinion for social and

political change.Wijewardene regarded 3 Ps – the Press, Parliament and

Platform – as the most important instruments of political action.

Even though he rarely wrote on his own and avoided getting involved

in active politics, he harnessed the power of the Fourth Estate to

advocate self-rule and liberal democracy.

And yes, he made good money in that process. So what? Despite their

public service remit, newspapers are not charities. Neither should they

be government agencies sustained on public funds.

The challenge is to make honest money while serving readers,

advertisers and society at large.

Those who lament the advertising ‘tail’ wagging the media ‘dog’

should study Wijewardene’s business practices. He was not beholden to

his advertisers. For example, Hulugalle recalls a disagreement between

Lake House and the then cinema monopoly over advertising rates. When the

cinema owners boycotted his newspapers, Wijewardene threatened to enter

the cinema business himself – and sent his trusted aide Hulugalle to

Bombay to negotiate terms with movie distributors. The idea was

abandoned only when the cinema ads were resumed.

Mass production

As an astute publisher, Wijewardene was not intimidated by new

technologies. He industrialised our newspapers which had remained

largely cottage industries until the 1920s. He invested in new printing

presses, as well as in improved productivity across the board.

Wijewardene transformed our newspaper industry from limited

circulation to mass production. At the time he started, the average

daily had a circulation of around 3,000 to 4,000 copies. By the time he

died in 1950, Dinamina was selling around 70,000 copies and Daily News,

55,000 copies according to his biography. The total population at the

time was 6.6 million (1946 Census).

In the absence of independently audited circulation figures, we

cannot be certain how well – or poorly – our newspapers are selling

today. But indications are not promising. I have been involved in a

state of the media study for the past year (due to be released in May),

and there is evidence that market survival is a big struggle for many

smaller publishers.

More and more Lankan newspapers are being kept alive not to make any

profit, but for influence peddling and political purposes. And in at

least one case, the co-operatively owned Ravaya, reader donations were

actively solicited recently to keep the paper alive.Worldwide, print

journalism’s established business models are crumbling, with decades-old

publications closing down or going entirely online (The Independent

newspaper in the UK is the latest to do the latter). Advertisers usually

follow where the eyeballs are moving.

So what would D. R. Wijewardene do if he confronted today’s realities

of gradually declining print advertising share and readers migrating to

online media consumption? How might he respond by going back to his

founding goals of political action and social change through the 3 Ps?

Credibility

My guess is that he would invest in radio and/or television, with a

strong digital integration. He might even find a viable income stream

from digital and online publishing without locking up public interest

content behind pay-walls. We can only speculate, of course. Perhaps the

more pertinent question to ask is: Where are the budding D. R.

Wijewardenes of the 21st Century? What are their start-ups and how are

their dreams unfolding? Are they trying to balance reasonable profits

with public interest journalism?

In my view, the biggest decider of success or failure – today, as it

was a century ago – is not the medium, but the message. To put it more

bluntly, it’s credibility, stupid!

In my own lifetime of five decades, I have seen two leading

publishing houses wither and die – the once venerable Times of Ceylon

(in 1985) and Independent Newspapers (Dawasa Niwasa, in 1990). The

reasons for their demise were complex, but they had only just invested

in modern offset printing. They failed not because of any technology

deficit, but due to losing credibility and societal relevance.

That lesson presents an imperative for ALL media, old and new: engage

your audiences and grow, or stray away from it and head to obsolescence.

Being large, loud and arrogant, is not a guarantee of survival (remember

the dinosaurs).

Being kept on ‘life support’ on public or private money can (and

must!) also has sane limits.

In the coming years, waves of technology, demographics and economics

will sweep away some relatively good media along with much of the

deadwood that deserves extinction (even plant-eating dinosaurs didn’t

make it). It is the adaptive and credible players who will be left to

write tomorrow’s first drafts of history.

I believe journalism will outlive newspapers in their current

industrial form. What matters more, in the long run, is serving the

public interest using whatever tools and forces that we can tap.

[Trained as a science writer, Nalaka Gunawardene has worked in print

and broadcast media but now spends most of his time blogging, tweeting

and researching on new media trends.

|