The truth that got fictionalised

In Woolf’s ‘Village in the Jungle’:

by Isuri Kaviratne

‘No

jungle was more evil than the jungle which lay about the village of

Beddegama,’ writes Leonard Woolf in his epic opus ‘Village in the

Jungle’ juggling with the evil of the forest and the evil of the people.

Silindu, the protagonist of the story, fears the evil of the jungle and

overlooks the evil of the people, which Woolf successfully depict

throughout the story where Silindu ends up murdering two people;

Arachchi and Fernando. ‘No

jungle was more evil than the jungle which lay about the village of

Beddegama,’ writes Leonard Woolf in his epic opus ‘Village in the

Jungle’ juggling with the evil of the forest and the evil of the people.

Silindu, the protagonist of the story, fears the evil of the jungle and

overlooks the evil of the people, which Woolf successfully depict

throughout the story where Silindu ends up murdering two people;

Arachchi and Fernando.

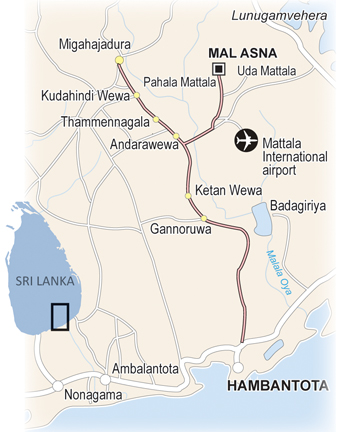

Being the AGA of Hambantota from

1908 – 1911, Leonard Woolf travelled to the farthest corners of

Hambantota, meeting Silindus, Arachchis, Punchi Menikas and Hinnihamis

and many others who inspired him to write his epic. Over a hundred years

later, we trace the footsteps of Woolf and unearth some of the true

stories of the villagers from the depth of the jungle along the

Meegahandura Road, which was the base of ‘The Village in the Jungle.’

Story 1:

The Story of Silindu

He is known as Mudiyanse. Old and enjoying retirement, he relates the

story of Silindu, his great grandfather, who lived in Mal Asna Gal Wewa,

a small village along the Lower Mattala Road. It is not known whether

Mudiyanse’s great grandfather had the ‘slightly mad’ and ‘lazy’

characteristic of Leonard Woolf’s Silindu, but he inspired Woolf to

weave a story around the incident where Silindu was convicted of two

murders.

As Mudiyanse recounts, ‘trouble’ began when a new ‘Opisara’ was

appointed for the Upper Mattala Village. The new ‘Opisara’ considered

the powers of the longstanding ‘Opisara’ in Lower Mattala and his

father, the Registrar, who maintained a high regard among the villagers,

a threat to his new position. He hired Silindu to ‘take care’ of the

two, and gave his gun with a promise to save Silindu if he got caught.

Similar to ‘The Village in the Jungle’, where ‘all the families (in the

village) are closely related by marriage’, Mudiyanse says his family

tree includes Silindu as well as the ‘Opisara’ and the Registrar who

were murdered.

As

narrated by Mudiyanse, Silindu lured the ‘Opisara’ of Lower Mattala out

of the house, pretending to get him to inspect his chena that was

destroyed by a herd of buffalos, and shot him en route in the thick

forest. On his way back, he stopped near ‘Opisara’s house, and shot the

Registrar, who was enjoying his morning tea, from afar and walked

straight to meet the ‘Opisara’ of Upper Mattala. As

narrated by Mudiyanse, Silindu lured the ‘Opisara’ of Lower Mattala out

of the house, pretending to get him to inspect his chena that was

destroyed by a herd of buffalos, and shot him en route in the thick

forest. On his way back, he stopped near ‘Opisara’s house, and shot the

Registrar, who was enjoying his morning tea, from afar and walked

straight to meet the ‘Opisara’ of Upper Mattala.

|

Remains of the gallows where criminals were hanged |

This story gets woven into ‘The Village in the Jungle’, where Silindu

murders Arachchi and Fernando in an attempt to protect his daughter,

Punchi Menika, and avenge the death of his other daughter, Hinnihami,

both of whom he was particularly attached to.

Mudiyanse says the tales he heard includes a side story where Silindu

meets the deceased Registrar’s brother on the way to Upper Mattala to

meet the new ‘Opisara’, but slips into the forest to avoid meeting him,

and even killing him, even though he had the chance.

The ‘Opisara’ of Upper Mattala had instructed Silindu to go to the

Hambantota Police station and surrender himself, and accordingly,

Silindu had walked approximately 40 kilometres to do so. Back then,

there had been a total of 12 police officers stationed at Hambantota

police and when Silindu walked in, only three had been present.

Mudiyanse’s family has a set of poems traditionally passed down in

the family, reminding the readers of Silundu’s sister and “the chants

peculiar to Karlinahami … who had learnt it from her mother.” They

believe that Silindu visited his wife, name unknown, before heading to

the police station and sang this to let her know of the poverty that

compelled him to commit ‘evil ‘deeds, demanding to know whether it

saddens her to see him going to prison.

“Silindu didn’t have any daughters. He had sons,” says Mudiyanse,

believing this to be the main difference between the fictional and real

Silindu.

The conversation between the police officers and Silindu, when he

confessed to the murders, is sung thus:

The police officers had initially been reluctant to accept Silindu’s

confession, and then assuming he had come to the police to kill them

too, had sent one officer to the Tangalle Police station asking for back

up. Mudiyanse recounts that the police has entertained Silindu to kill

time, agreeing with him on how hardships makes people vulnerable enough

to make wrong decisions, and had arrested him as soon as the backup

arrived from Tangalle.

Little

is known about Silindu’s trial, but he had never returned home. The

family believes he was expelled to the Andaman Islands. Little

is known about Silindu’s trial, but he had never returned home. The

family believes he was expelled to the Andaman Islands.

Story 2:

Mal Asna Gal Wewa and Meegahajandura

Gun shots were common in the area as many used to hunt for food, “so

when my maternal grandparents heard the gun shots, they thought it was

hunters in the forest,” says V.G. Somarathne Vidanagama, a resident of

Lower Mattala. His grandparents’ families were two of the five families

in the village back then.

Recalling the stories he has heard from his grandparents, Vidanagama

says the Tamarind tree under which the ‘Opisara’ and his father were

buried is still there, but no one really knows which one it is. Being

the dry zone, the forest has many Tamarind trees. However, the two

Palmyra trees that marked the boundaries of the age-old village of Mal

Asna Gal Wewa are still intact, one tree adjoining the Gal Wewa lake,

which the villagers, including Silindu and his family, used to frequent.

The village still has ‘the jungle surrounding it, overhanging it,

continually pressing in upon it’. Through the village lies a footpath

that is currently used by farmers as a shortcut to their paddy fields,

the same path along which Silindu lured the ‘Opisara’ and murdered him,

and returned to kill the Registrar.

|

The Tamarind tree under which ad hoc court sessions were

held by Leonard Woolf to solve minor disputes among

villages, from 1908 to 1911, as the AGA of Hambantota.

(Pictures by Susantha Wijegunasekara) |

S.A. Munasinghe, a retired principle in Meegahajandura owns the land

with the massive Tamarind tree winged across the front lawn, providing a

cosy shady area in the otherwise scorching surrounding, as it must have

done a hundred years ago, when Woolf conducted hearings under it. “The

‘Vidane Aarachchi’ back then was my late wife’s grandfather, Don Samuel

Nallaperuma, and we have heard many stories about the ‘sudu mahattaya’

coming to our village to solve disputes”. He admits that the only murder

case they’ve heard of in the area back then was the story of Silindu.

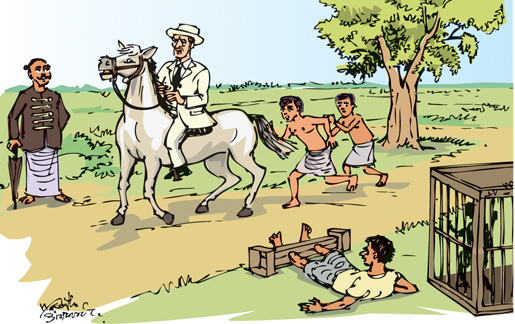

Leonard Woolf, Munasinghe has heard, used to come on a horse,

surrounded by village kids who tried to keep up with the horse.

Following the horse was a cart that carried Woolf’s necessities. They

would arrive at the Tamarind tree in their garden, where Woolf used to

listen to minor complaints and solve disputes. There had been a small

cage made of wood and a ‘Dandu Kanda’ for immediate punishments.

Most of the cases he heard under the tree had been about avoiding

taxes, marriage disputes, and gun permits. Many of them would be solved

the very same day. Others had been transferred to the Hambantota Court,

compelling the complainers and defendants to walk over 40 kilometres to

Hambantota town for the court hearings.

Story 3:

A hundred or so years later

‘The smell of hot air, of dust, and of dry powdered leaves and

sticks’ are still characteristics of the pockets of villages that

eventually became the inspiration of ‘The Village in the Jungle’. The

jungle that glided into Punchi Menika’s doorway has been cleared in

pockets; villagers have fought back the ‘evil’ jungle and burnt it to

clear lands for agriculture. Many of the villagers are encroachers and

had settled in the area recently. In the old families, the youth have

little knowledge of the ancient stories, and the elderly are too old to

remember the interesting facts.

The development in the area is indicated by the carpeted main road

from Hambantota to Meegahajandura, constructed recently as an addition

to Mattala Airport. But a peek inside the villages reveal small by-lanes

and footpaths that stretch for miles along the pockets of forests that

are yet to be cleared, resonating Woolf’s words ‘trees and bushes which

knit the whole jungle together into an impenetrable tangle of thorns’.

It is easy picture the image Woolf had when he wrote ‘If you walk all

day through the jungle…, you will probably see no living thing’.

Though

the main occupation of the villagers is paddy cultivation, Woolf wrote

‘they only cultivated rice about once in ten years’ due to lack of rain.

People are still struggling due to lack of water and manage a meagre

harvest in one season, and shift to chena cultivation for the rest of

the year. J.K. Channaka of Ketan Wewa village says drinking water is

being distributed by the Municipality Council. Though this is the

situation from Gonnoruwa to Meegahajandura, due to reconstruction of Mau

Ara canal in the late 1990s, paddy cultivation has improved in

Meegahajandura. Here, people have better houses, many own motorcycles or

three-wheelers, some even own a car, and the dryness that is visible

just two kilometres south from the village seems to have evaporated. Though

the main occupation of the villagers is paddy cultivation, Woolf wrote

‘they only cultivated rice about once in ten years’ due to lack of rain.

People are still struggling due to lack of water and manage a meagre

harvest in one season, and shift to chena cultivation for the rest of

the year. J.K. Channaka of Ketan Wewa village says drinking water is

being distributed by the Municipality Council. Though this is the

situation from Gonnoruwa to Meegahajandura, due to reconstruction of Mau

Ara canal in the late 1990s, paddy cultivation has improved in

Meegahajandura. Here, people have better houses, many own motorcycles or

three-wheelers, some even own a car, and the dryness that is visible

just two kilometres south from the village seems to have evaporated.

J.B. Dingihamy and K.G. Sedarahamy of Gonnoruwa say the only

transport available at the time they arrived in the area in 1970 was a

bullock cart to go to Hambantota. Currently, there is a bus service on

the main road, every 90 minutes. Though there are primary and secondary

schools every three to four kilometres along this stretch, people have

to travel 20-30 kilometres to the Hambantota hospital in cases of health

emergencies.

Sujith Prasanna¸ a resident of Lower Andarawewa says when he first

arrived in 1983; there were only bullock carts, and one van to transport

people. But “we have to carry a ‘keththa’ with us to clear the forest

for the van to move through.” His words draw uncanny similarities to

Woolf’s description of people carrying ‘keththas’ to clear the jungle

when travelling in carts.

Being a farmer, Prasanna says lack of rain has left him with no

occupation. “I’m willing to do any work that will get me some money for

my three kids,” he says, bringing to mind another reminder of Silindu’s

tale. |