A silent killer and its unknown cause

With an increasing demand for kidney transplants,

scientific uncertainty in what causes kidney diseases remains a serious

dilemma :

by Rhitu Chatterjee

A small crowd of villagers waits at a low-slung concrete school

building in Pedda Srirampuram, a village in the south Indian state of

Andhra Pradesh. The early morning air is crisp and the men and women are

dressed in light shawls and sweaters. Each holds two plastic bags-one

with their medical records, the other with a clear plastic container of

their urine. They line up to be seen by one of four young men at two

large wooden tables.

A researcher named Srinivas Rao sits at the first table. "What's your

name?" he asks a short, wiry man who is next in line. "D. Kesava Rao,"

the man replies, handing over his medical records. Rao, the researcher,

flips through the pages, noting down details. "His kidneys are not

functioning at all," Rao remarks. "Both his kidneys."

Kesava Rao, 45, has chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology (CKDu)

and depends on dialysis to survive. "Every week I undergo dialysis, four

weeks a month," Rao says. A soft-spoken man with a ready smile, Rao has

worked all his life on construction sites or coconut farms. He lived a

healthy life and hardly ever saw a doctor, he says, until a fever led to

an exam and his diagnosis. Rao didn't have diabetes or, until his

kidneys failed, hypertension, the two main causes of chronic kidney

disease worldwide. Nor do most of the other villagers who have gathered

here, all chronic kidney disease patients, waiting to get a free blood

test for creatinine, a metabolite and a proxy for kidney function, and

give samples of urine and blood for research.

Rural disease

This region in coastal Andhra Pradesh is at the heart of what local

doctors and media are calling a 'CKDu epidemic.' There is little

rigorous prevalence data, but unpublished studies by Gangadhar Taduri, a

nephrologist at the Nizam's Institute of Medical Sciences in Hyderabad,

in the neighbouring state of Telangana, suggest the disease affects 15%

to 18% of the population in this agricultural region, known for rice,

cashews, and coconuts.

Unlike the more common kind of CKD, seen mostly in the elderly in

urban areas, CKDu appears to be a rural disease, affecting farm workers,

the majority of them men between their 30s and 50s. "It is a problem of

disadvantaged populations," says Taduri, who is leading the team of

researchers in the village.

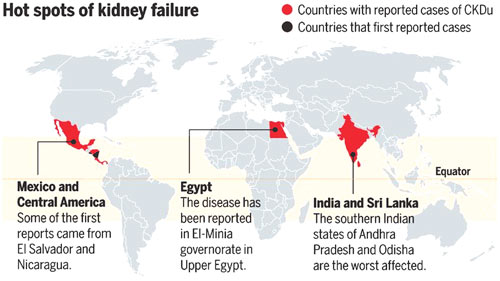

A rash of similar outbreaks in other countries has underscored that

it is a global problem. Some rice-growing regions of Sri Lanka have

their own epidemic, and the disease is rampant in sugar-producing

regions of Mexico and Central America. It has also been reported in

Egypt. Just about everywhere, prevalence numbers are scarce and

uncertain, but "there is a great deal of concern," says Virginia Weaver,

an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in

Baltimore, Maryland. "This is an illness that has substantial mortality.

People who would otherwise be working, raising families, are dying. It's

quite extraordinary."

Public health experts and researchers are alarmed and baffled. In

Central America, which has been hit the hardest, the leading hypothesis

is that this is an occupational disease, caused by chronic exposure to

heat and dehydration in the cane fields.

Here in Andhra Pradesh, Taduri and his colleagues think natural

toxins in the drinking water-lithium, for example-could contribute.

Using the blood and urine samples from Pedda Srirampuram, "we're going

to evaluate whether [trace elements] are really present in the body or

not," says C. Prabhakar Reddy, one of the researchers collecting the

samples.

But in India, as in Sri Lanka and Central America, researchers trying

to explain CKDu are pursuing a wide range of ideas, including excessive

use of over-the- counter painkillers and exposure to pesticides.

Nephrologist Ajay Singh of Harvard Medical School in Boston has found

high levels of silica, present in some pesticides, in the region's

drinking water, and thinks it could be responsible. "There's a smoking

gun," he says, though he concedes: "I don't know whether the smoking gun

is responsible."

As the global scale of the disease becomes clear, the search for

answers is accelerating. The beginnings of an international scientific

network to study CKDu are taking shape, and researchers are working on

simple, accurate diagnostics so that they can map incidence around the

globe-and try to correlate it with potential causes.

|

Two Indian kidney donors (Hindu) |

|

Like most places where CKDu is rampant, India doesn't have a good

idea how many people have the disease (also known as CKDnT, for

non-traditional causes). But the anecdotal evidence from Andhra Pradesh

is sobering. We have "almost 126 widows" of men who have died from CKD,

says Rajni Kumar Dolai, the chief of the village of Balliputtuga. The

total population of his village is 3270, which implies that almost 4% of

its inhabitants have died of the disease.

By screening village populations in a van equipped with an ultrasound

machine and other diagnostic equipment, Taduri and his colleagues came

up with their estimated incidence of 15% or more in this region. Most

people diagnosed with CKDu "didn't have any complaints that suggested a

kidney problem," Taduri says. "But ... their creatinine was high."

Ultrasound exams revealed that they had "shrunken" kidneys.

Shrunken kidneys

CKDu is so deadly in part because it is hard to detect. "It is a

silent killer," says A. K. Chakravarthy, a nephrologist in Nellore,

Andhra Pradesh. In the disease's early stages, people show no symptoms.

"By the time they find out, it is too late," he says. Their kidneys are

already beyond repair, leading to high blood pressure, weakness and

other symptoms. Access to dialysis here remains limited, even though the

state government of Andhra Pradesh has added facilities in recent years.

For many patients, death comes not long after their diagnosis.

Those lucky enough to get dialysis survive for several years, but are

unable to earn a living, pushing their families deeper into poverty. His

strength and endurance sapped by the disease and dialysis, Kesava Rao

can no longer provide for his family of five. His eldest son, now 20,

has had to step into his father's shoes. "He finished high school, and

then stopped studying," Rao says. "He's the primary breadwinner of the

family now."

In India, several research groups are on the trail of a cause. But

each team has used its own methods and tools, often in isolation, making

it hard to compare findings. Taduri and Singh, for example, have both

worked in Andhra Pradesh for years, and both have pursued the hypothesis

that the high levels of silica in drinking water could be responsible.

Silica dust is known to damage lungs and kidneys when inhaled, but no

one knows what it does when ingested.

Yet the two researchers had never met until recently. "I wasn't even

aware that this work was going on," Singh says about Taduri's work.

Whereas Singh thinks the silica comes from pesticides, Taduri believes

it leaches into the groundwater from bedrock. Singh admits the

researchers could have benefitted from a collaboration. "We need to

develop a coordinated approach."

Collaborative research

|

|

Credit for image: G.

Grullón/Science |

That is true beyond India. As scientists and public health experts

realize that CKDu is a global disease or set of diseases, they are

casting a wider net for possible causes. "We need to look at this from a

global perspective," Weaver says.

Some 30 Indian and international scientists, physicians, and public

health experts sit at a round table in a nondescript conference room at

The Energy and Resources Institute in New Delhi. The group is here for a

CKD workshop spearheaded by the La Isla Foundation, a non-profit group

that works with affected communities in Central America. The goal of the

January meeting: to create a global network of scientists studying the

disease.

The first task for the network is to determine prevalence, says Ben

Caplin, a nephrologist at University College London who works in

Nicaragua. "We need to know where are the hot spots of CKDnT," he says.

"Are there common environmental, occupational, and social factors shared

between CKDnT hot spots?"

But participants differ about how to define the disease. Caplin

proposes a working definition: "no alternative cause of CKD diagnosed by

medical professional, absence of diabetes, absence of hypertension." But

Singh says that the condition may well be a collection of diseases

caused by different factors in different places. By insisting on a

single definition, we are "already starting to have a bias on what the

causes may be."

Neil Pearce of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, the

only epidemiologist in the room, says screening for impaired kidney

function can be done without making assumptions about causes. "We're

trying to find populations with high prevalence and low prevalence. This

says nothing about the individual."

Getting a handle on prevalence will require a standard screening

test, however. Caplin, Pearce, and their colleagues are developing a

protocol that can be adapted for different populations: a blood test for

kidney function, a urine test, and a basic questionnaire recording the

participant's age, sex, occupation and income. The team is trying to

keep it simple and inexpensive, Caplin says. "We don't want to make it

too complicated and put people off."

The team hopes to publish the protocol in a peer-reviewed journal, so

that scientists in any country can use it to screen local or regional

populations with their own funds.

"I think that using a simple protocol that will be affordable in

different settings would really shed light on the extent and global

distribution of the disease," says Catharina Wesseling, an occupational

and environmental health expert at the Karolinska Institute in

Stockholm.

Silent killer

Wesseling studies CKDnT in Central America, where it takes an even

heavier toll than in India. "Just look at the mortality numbers," says

Jason Glaser of La Isla. In Chichigalpa, Nicaragua, for example, "46% of

all male deaths are due to CKD," he says. "Seventy-five percent of

deaths of men between 35 and 55 years are due to CKD." By some

estimates, the disease has already killed at least 20,000 people in the

region.

If the disease hitting India is identical, research in Central

America could narrow the search for a cause. Recent studies there have

bolstered the hypothesis that CKDu results from long hours of work in

the heat with too little drinking water, leading to chronic dehydration.

Last year, for example, a study by Wesseling and her colleagues

showed that the disease has existed in Costa Rica at least since the

1970s, but that the death rate in Guanacaste Province has shot up from

4.4 per 100,000 men between 1970 and 1972 to 38.5 in 2008 to 2012 with

the expansion of industrial-scale sugarcane farms.

In another study, the same group showed that the kidney function of

cane cutters in one Nicaraguan community declined through a single

harvest period. "These people have a very scary deterioration of kidney

function over the harvest time," Wesseling says.

A pilot study she and her colleagues did last year hinted at how

chronic dehydration does its damage. They found high levels of uric acid

crystals in cane cutters' urine, especially at the ends of their shifts.

Those crystals could be injuring the kidneys, the researchers proposed.

"This is an important mechanism we hadn't thought about," says Richard

Johnson, a nephrologist at the University of Colorado, Denver, and an

author on the study.

But the case is far from closed. "I absolutely don't think that heat

stress and dehydration are the only part of the story," Glaser says.

"You see different severity [of the disease] in different places." Like

him, most scientists are not yet ruling out other factors.

Even before scientists know for sure what causes the disease, Taduri

says communities can take steps to reduce the risks. Providing clean

surface water sources for drinking, urging people to drink more water at

work, and advising them to stay away from pain- killers will improve

their health anyway, he contends. In El Salvador, Glaser and his

colleagues are working to expand a pilot study called the Worker Health

and Efficiency program, which prescribes frequent rest and hydration for

workers.

Fears and frustrations

Meanwhile, in CKDu-affected communities in southern India, fear and

frustration are on the rise. Now, says Taduri, villagers in Andhra

Pradesh refuse to come for screening, fearing stigma. When a man is

diagnosed with the kidney condition, "his entire family will feel him as

a burden," explains Dolai, the village chief in Balliputtuga.

On a nearby farm, a group of men stand in a circle peeling coconuts.

Most are sweating in the midmorning sun. Each stands over a blade longer

than his forearm, its wooden handle planted firmly in the soil. They

pluck coconuts from a pile and swiftly pull each one over the blade,

peeling the thick husk away from the hard, brown inner shell.

The men talk as they work, and the conversation turns to their

creatinine levels. "Mine is 1.4," says a young man in his 30s. "Mine is

1.3," another says. "One point nine."

"Two." For half the men, the levels are either borderline or high.

All work long hours under the sun, with too little water to drink.

Their legs and backs often hurt when they return home in the

evenings, and they turn to painkillers or alcohol, even though they know

both are bad for their kidneys.

The men understand they are at risk of chronic kidney disease, but

believe they can do little to stop it from progressing. Rest is not an

option, one says. "We have the disease, but we still have to work to

earn a living."

- sciencemag.org |