Storm in the Tea cup

Estates failing: exports lowest since 2002:

By Sunday Observer Economy Unit

A slump in demand which began with the global economic crisis in 2008

has been exacerbated by unrest in the Middle East and Russia which

consume 60% of Sri Lanka's tea exports.

|

|

(Pic: by Ranga S. Udugama) |

Last month, export volumes for tea declined to 21 million kilograms,

the lowest figure in 14 years and total tea production is likely to fall

under the 300 million ton mark in 2016 - back to levels seen around the

year 2000.

As production and exports have fallen, costs have risen with the

amount the plantations have to pay for labour, transport and fertilizer

having increased steeply over the past 5 years.

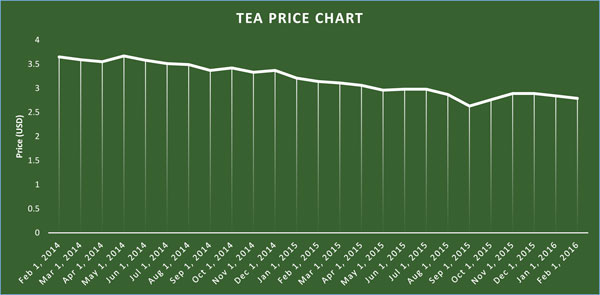

Since mid-2015 the price of tea on the Colombo tea auction has fallen

by over 20% - with a kilo of tea now trading between Rs 60-80 lower than

a year ago. In dollar terms the decline has been even steeper with the

past two years seeing prices fall by over 35%.

Across the sector tea plantations are reporting losses and reducing

production at a time when production in rival producers such as Kenya

and India has stabilized and begun to increase.

The present situation represents the most severe crisis in Sri

Lanka's plantation sector since privatization in 1992. The role of tea

plantations in our economy cannot be overstated. Tea generates over 1.8

billion dollars of revenue (the nation's second largest source of export

revenue) and the tea industry supports over 2 million people or near 10%

of the total population.

Given the vital importance of tea, the Sunday Observer spoke to a

range of stakeholders to ascertain a way forward for the industry,

particularly, the RPCs which dominate the industry but now find

themselves struggling to stay afloat.

What is an RPC?

The Regional Plantation Companies (RPC) were formed in 1992, the

result of efforts by Presidents JR Jayawardene and Ranasinghe Premadasa

who moved to privatize the vast majority of the estates the state had

nationalized in the 70s under the land reform program.

Driven by SLFP governments in the 70s all plantations greater than 50

acres in extent were taken over by the state - however, the state lacked

the capability to effectively manage the plantations and most estates

were severely mismanaged and loss-making following nationalization.

President Jayawardene reorganized the state's plantation holdings

into 22 Regional Plantation Companies with each company comprising

several estates. They were then sold to the private sector via a bidding

process and the RPCs listed on the Colombo Stock Exchange.

In many cases control of the RPCs passed to conglomerates, e.g.

Hayleys, Aitken Spence, Richard Pieris, John Keells all acquired

controlling stakes. Today, there are 20 privately held and 3 state

controlled RPCs.

The creation of private sector driven RPCs reversed a sharp decline

in estate productivity and the government no longer has to bear the cost

of loss making estates. As of 2016 the RPCs produce approximately 40% of

the country's tea (and rubber)and directly support 200, 000 workers with

a total of 1 million plantation residents - making RPCs a key part of

the plantation system and broader economy.

RPCs: A failed experiment?

Despite being an obvious success in terms of stemming state losses

and extricating the state from direct management of thousands of acres

of land, the privatized RPC system has long faced criticism from experts

and stakeholders.

It is alleged, in many cases, privatized estates failed to live up to

their potential as their new owners, while effecting an initial

turn-around, soon began draining profits from the RPCs as management

fees and failed to reinvest sufficiently in the estates.

As proof, critics point to low yields and productivity in many

plantations and a low rate of replanting.

"Two % of the extent of a plantation should be replanted every year,

but this never happened," said Lalin De Silva a former planter and

retired editor of the Plantation Society Bulletin. He added: "In many

estates tea bushes are nearly 100 years old and can't produce high

yields. They (RPCs) say they can't invest now because prices are bad.

But, what happened when prices were good, there were years when

production and prices were excellent - why didn't they make investments

in productivity?"

There have been allegations of outright asset stripping with the

management of some plantations accused of felling timber, selling

livestock and other assets to make profits.

"They under-invested", said Muthusivalingam, Head of the Ceylon

Workers' Congress Union (CWC) - the largest union of plantation workers.

"Living and social conditions in the plantations were neglected, they

can't just blame workers for lack of productivity when they didn't

invest sufficiently in roads, and facilities."

The case for RPCs

While there is criticism of RPCs - a number of plantation experts and

representatives of the plantation companies argue that the RPC system

has been a success and helped revive Sri Lanka's tea industry.

"Overall their performance has been fair,"said Romesh Dias

Bandaranayake, economist and former head of the Plantation Management

Monitoring Division. "Given the [loss-making] condition they were in, in

1992, we've seen the RPCs make a positive contribution to the economy

and government revenue."

Mr Dias explained that the RPCs have contributed Rs. 7 billion to the

government in terms of lease renewal payments alone, and further

contributed in terms of taxes, EPF payments dividends and re-investment.

"Contrast this to the remaining government run plantations - the

Janatha Estate Development Board, which consumes over a billion rupees

of state funds annually. Overall, the RPCs have increased production and

revenue - of course not all the estates have performed equally well but

the strategy of privatization via listing on the stock exchange has

proved successful and robust."

From1992 to 2002 there was a demonstrable increase in tea production

from 200 million to 300 million metric tons.

"We have reinvested far more into plantations than we have taken

out," said Roshan Rajadurai, Chairman, Planters' Association, which

represents the management of all RPCs. "Despite claims by critics, over

60% of the acreage in our tea plantations have been replanted ,

according to Plantation Ministry statistics, so that claims of

mismanagement are simply false."

Even critics of RPCs management agree that a return of the estates to

state control is not desirable. "The workers are worse off in the state

run plantations than the RPCs, so we are not in favour of a return to

state control," said Muthusivalingam CWC President.

A 150 year old model

But, there's no denying that yields on Sri Lanka's tea planttions are

low and avenues for value addition and mechanization have not been

sufficiently explored.

"If you look at the average yield of a Sri Lankan tea plantation it

is around 1,700 tons per hectare while in Kenya and better run estates

in India, the figure is well above 2,000 kilos per hectare- even though

we have good climatic and soil conditions. This is hard for plantation

companies to explain" said Janen Fernando of Verite Research.

The government has also accused the RPCs of mismanagement. Last year,

former Minister of Plantations Lakshman Kiriella insisted the RPCs raise

wages or face action from the government.

Sri Lanka's RPCs have also failed to diversify with the potential for

the production of spices, rearing livestock and dairy production, not

being sufficiently explored. Plantations remain reliant on a 150 year

old labour model where workers spend a lifetime plucking tea for low

wages. "The RPCs need to provide opportunities for the youth on the

plantations, they need avenues for advancement and training - it must be

possible for them to become managers and rise out of poverty," said

Harin Fernando Minister of Telecommunications and Digital Infrastructure

and long-time campaigner for plantation rights.

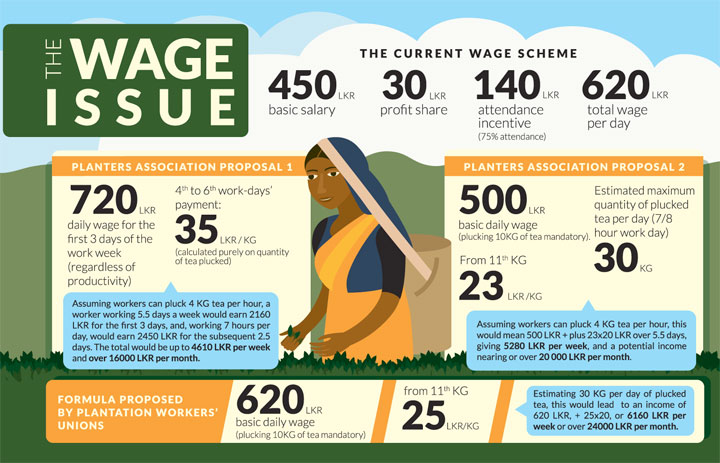

The wage issue

Sri Lanka's tea estates depend on the manual labour of hundreds of

thousands of low-wage workers.

As the cost of living has risen, unions are demanding an increase in

wages and a government directive stipulating a Rs 2,500 (per month)

salary increase for every worker has put pressure on the plantations to

increase salaries. However, given the diminished revenues, RPCs claim

they are in no position to raise salaries.

Since 1992, representatives of RPCs and trade unions have met

biannually to negotiate standard wages for plantation workers, known as

the Collective Agreement (CA) which fixes wages for a 48 month period. A

new CA is due to be negotiated this year.

The RPCs insist they are willing to consider an overall wage increase

in line with or even exceeding the government directive if productivity

and not simply attendance is made the basis for payment.

At present, the bulk of a plantation worker's wage is calculated on

the number of days he or she reports to work - not on the basis of work

done or the weight of tea plucked.

All stakeholders contacted by the Sunday Observer agreed that

productivity based pay is essential in terms of increasing yields and

securing the future of the estate sector.

They

point out that rival tea producers like Kenya and India have now adopted

productivity based wage formulas which reward workers for plucking more

tea. However, both sides failed to agree on how a new productivity based

wage formula would be structured. They

point out that rival tea producers like Kenya and India have now adopted

productivity based wage formulas which reward workers for plucking more

tea. However, both sides failed to agree on how a new productivity based

wage formula would be structured.

"We cannot just increase wages - we are struggling, in the past we

have increased wages by as much as 40%, but without in increased

productivity it threatens the whole industry," said Rajadurai.

Union officials on the other hand argue, estates must do more to

enable workers to be more productive.

"We are willing to accept a move to productivity based pay but it

must allow workers to earn a fair wage - which means at least Rs 2,500

or more a month, and RPCs must provide the conditions - maintenance,

sufficient workings days, etc.," said CWC Leader Muthusivalingam.

[Experts say]

The Sunday Observer spoke to stakeholders from across the

plantation industry - below are a summary of their suggestions for the

overall improvement of the RPCs and the broader tea plantation sector

Productivity-focused

The movement to productivity rather than attendance based wage is

critical in the long term survival of the industry. Emphasizing

productivity will boost yields, however, any new mechanism must allow

workers to earn a fair wage and must also take into account the work

they do on the plantation that isn't connected to plucking, e.g.

maintenance, weeding etc.

Checks and Balances

Given a history of serious mismanagement on government run

plantations direct government intervention across the sector is

undesirable, however, government oversight is needed as a check on

RPCs.The Plantation Management Monitoring Division of the Ministry of

Plantations was established to allow the state a mechanism for

regulating and monitoring the RPCs. The Division has been largely

inactive over the past decade but a revived PMMD constituting qualified

state officials and retired senior RPC managers could play a role in

ensuring RPCs fulfil their social and economic mandate.

A board with clear powers could devise an assessment methodology with

annual reviews and rankings of the RPCs and then take action against

those found under performing.

The RPCs must be allowed to function as businesses, albeit with a

social responsibility, while the primary role for caring for estate

populations must fall on the state. When plantations were established

more than a century ago they were entirely responsible for the

communities who lived within them. Health, education and services to

plantation villages were provided by the companies. Today, plantation

communities must be integrated with mainstream society. Clinics and

schools within the plantations are the responsibilities of the state but

the roles for both parties must be clearly delineated.

Training and opportunities for youth

Accessible colleges for technical training must be established

allowing youth on plantations options for progressing into managerial

roles within the tea industry and avenues to seek skilled jobs outside

the plantation sector. The government, RPCs, NGOs and the Private sector

must work together to establish training centres for plantation youth.

Stronger welfare

An expanded welfare scheme operated primarily by the government but

in concert with RPCs and unions is important for ensuring an adequate

quality of life for workers. Bolstered pension, welfare and insurance

support will keep workers from poverty. Today, the injured, sick and

elderly workers struggle to make ends meet.

Value addition

The vast majority of RPC income is derived from the sale of bulk tea

on Colombo's tea auction. RPC must encouraged to emphasize value

addition with companies packaging and directly exporting a greater

proportion of their tea. Tax and loan concessions can be given for the

import of packaging machinery accompanied by targets for value added

exports.

Gender equality

The disparity in pay between men and women where men currently earn

significantly more than women for a day's labour must be rectified as

women typically work longer hours than men and act as primary caregivers

spending the entirety of their income to support their families. |