|

observer |

|

|

|

|

|

OTHER LINKS |

|

|

|

Rebuilding Sri Lanka one house at a time

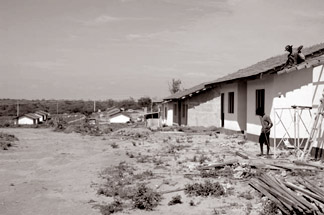

For days after the tsunami hit Asia, I stood in front of my television, transfixed by tales and images of children being swept from their parents' arms, of elderly men clinging to tree branches until their muscles burned and their fingers went raw, praying for the water to recede before their strength gave out. Half the world's charities were soliciting donations, but writing a cheque felt too remote. I wanted to help in a more tangible way, to feel, in some part, the impact of the destruction that I'd been experiencing in my living room via tidy, two-minute news packages. Apparently, I wasn't alone. Dozens of Westerners were flying to the disaster zones to offer themselves up as unpaid relief workers-and were being turned away. Unskilled workers were seen as more of a burden than an asset. When I learned that Baton Rouge-based tour company Global Crossroad had coordinated a working vacation that offered ordinary citizens a chance to build houses for displaced families in Sri Lanka, I was cautiously excited. My only construction experience at that point had been assembling an Ikea dresser, but the cheerful programme director assured me that there was plenty of work for unskilled labourers like me. I was also uneasy about the prospect of a for-profit company earning money from someone else's misfortune. Global Crossroad insisted that it was merely covering costs. Of the $1,100 programme fee, $400 went to construction materials, and most of the remainder was earmarked for food, lodging, and ground transportation. Two hundred dollars was applied to administrative expenses, primarily to pay the in-country coordinators. My doubts were somewhat assuaged when I learned that the cost estimate for Habitat for Humanity, a non-profit organisation doing a similar project in Sri Lanka, was about the same amount. Global Crossroad has coordinated volunteer vacations around the world for three years, though its projects, such as teaching disadvantaged children and feeding orphaned elephants, have traditionally been less urgent in nature. After the tsunami, however, the phone rang off the hook with calls from volunteers pleading to be sent to Sri Lanka. Two weeks later, the company launched a house-building project in the town of Galle, on the southwest coast. A hundred and fifty applicants signed up in the first three days. By the time I returned home late last March, the company had arranged reconstruction trips for 600 people. But wouldn't the $3,000 that you shell out for the flight and the programme fee buy a lot more relief than the one or two houses you could help complete in two weeks? In essence, wouldn't it be better just to write the cheque and skip the trip? Maybe. "Five dollars can buy so much over there, so it might make more sense to use the money you'd spend on airfare and hotel to help hundreds of people," said Michael Spencer, a public-affairs coordinator for the Red Cross. Different purposesBesides, volunteerism fulfils a different purpose than a cash donation. "If you invest time rather than money, you're being an ambassador," says David Minich, director of Habitat for Humanity's Global Village programme. "You're promoting the idea that we're all connected despite our huge cultural barriers." I arrived in Colombo, the Sri Lankan capital, 10 weeks after the tsunami. For many outsiders, the devastation had already begun to recede into memory. Along the coastal road that curves from Colombo to Galle, however, reminders of the destruction were rampant: houses that had been reduced to jagged fragments of wall or bleached wooden skeletons; staircases leading to nonexistent second floors; turquoise fishing boats snapped in half. For all the gutted buildings that lined the road, and all the money that had allegedly been pouring into Sri Lanka, I saw not a single new house going up until we reached the town of Hikkaduwa, two hours from Colombo. Even then, there were only a handful. Locals said it was a planning issue: With so much of the coastline destroyed, the overwhelmed government was busy trying to allocate funds and decide on building sites. Meanwhile, 500,000 people were living in tents, and monsoon season was six weeks away. Four hours after starting out, we pulled into Galle. At the bus depot, I recognized a statue of the Buddha sitting in the lotus position in a white concrete shrine. I had first seen it on a newscast, a serene orange-robed figure surrounded by rushing water, two young women clinging to one of its knees. Now, people scuttled past it without a glance. The next afternoon, the 16 members of our project team assembled at our guesthouse, a minty green replica of a Dutch colonial. We ranged in age from 23 to 67; we hailed from Canada, the US, the UK, and Australia; and among us were an accountant, a graphic designer, a songwriter, a flight attendant, and a retired business owner. We had all come with different levels of experience: There were a handful of unskilled but well-intentioned people like me, but thankfully, there were also Richard, a retiree from Austin, Tex., who had worked on 12 construction projects around the world; Debbie, from Kansas City, Mo., who ran a remodelling company with her husband; and her son-in-law Greg, a broad-shouldered, 27-year-old ironworker. Some people brought other valuable skills. Caitlin, an avid gardener from New York City, arrived with a suitcase full of organic seed packets, hoping to start a garden for the inhabitants of each new house. Reconstruction for neediestWith more than 20,000 people in the district of Galle displaced from their homes by the tsunami, Global Crossroad tries to ensure that its reconstruction efforts are focused on the neediest families. The company places an ad in the local paper, asking families to submit an application, and then interviews the family and inspects the damage to their home. Our project coordinator, Paul Ferreira, explained that we'd be building two houses: one for the family of a young man with cancer whose house had been destroyed by the tsunami, and another for the family of a fisherman who had lost not only his house, but also the boat that enabled him to earn a living. Our days were divided equally between work and relaxation. Every morning at 7 a.m., we were driven 20 minutes inland to our work site in Bataduwa, a languid village where kingfishers sailed over the rice fields and locals gathered at the village well to bathe. During our orientation, Paul had advised us to abandon our Western ethos of maximum speed and efficiency. Our supervisors would be Sri Lankan masons, and as their apprentices, we'd adapt to their building methods. That meant no shortcuts: no power tools, no cement mixers, no backhoes. Instead, we had Iron Age implements to dig the houses' three-foot-deep foundations-pickaxes, shovels, and a heavy tool that fell somewhere between a crowbar and a spear, meant to break up the rocky soil. It's a common philosophy on this kind of project, one that Habitat for Humanity employs as well. Despite the fact that you could knock out a lot more houses with some engine power, the thinking is that control over a reconstruction project should ultimately rest in the hands of the locals. There's a practical side, too: Replacement parts are scarce in Sri Lanka. The first day, we cleared brush and dug foundations-gruelling work that was exacerbated by the 98-degree heat and ferocious sun. It took about half an hour of chopping at roots with the dull edge of a hoe before we were drenched. The projectThroughout the two-week project, we were under the tutelage of head mason Lasanta, a lanky, sloe-eyed 26-year-old dressed like an Italian playboy in a pressed black dress shirt and fitted jeans. Lasanta spoke only a few tentative words of English ("yes," "no," "here," "there," and "cement"), and the Westerners knew even less Sinhala. But pantomime proved to be a fine communication method. On the few occasions when it did not, we relied on Ranjith, Lasanta's second-in-command, a sweet, perennially smiling man whose 18 words of English picked up where our two words of Sinhala left off. At noon, we were driven 20 stifling minutes away to a lovely beach. We'd tumble out of the van, peel off as many clothes as we dared, and run into the ocean. The water was warm and embracing, the surf powerful. Our lunches-spicy vegetables, thin rice noodles, and a piece of grilled fish marinated in tamarind and spices-were delivered to us as we sat beneath the palms. Because the afternoon heat was so intense, we worked for only a couple more hours after lunch before retreating to the guesthouse to shower and relax before dinner. One day, we returned to the site after lunch to find the family whose house we were building. The young couple and their two tiny daughters in matching pink dresses smiled shyly. W.A. Chandana, the man of the house, was 27 and had been diagnosed with leukaemia. He and his wife, Rasangika, had 2-year-old twins, and her belly was swollen with a third child. A labourer in a garment factory earning $3 a day, Chandana had lost his house and all of his possessions in the tsunami. He and his family were living under a piece of tarp stretched over stakes, with a thin mattress on the ground, perpetually damp from the humidity and torrential evening rains. Meeting Chandana's family lent urgency to the construction, and made every task feel worthwhile. We learned how to mix concrete - hauling bucket after bucket of it to the bricklayers - and we transferred dozens, maybe hundreds, of boulders from one pile to another, where the masons could access them. By the end of the first week, I'd learned how to puzzle boulders together in the foundation to build a retaining wall, how to lay cinder blocks, and how to make support columns out of rebar and wire. Our progress was slow, and there were definitely moments when our tasks felt Sisyphean - the afternoon we spent shovelling out a six-foot cesspit with half of a coconut shell, for example. Despite the heat, despite the occasional sense that I was paying for the opportunity to work in a gulag, I found that incredibly, surprisingly, I was having a great time. Our camaraderie helped sustain us, as did the constant stream of villagers who dropped by to kick-start us with cookies, bananas, and homemade caramels. One morning an old man and his granddaughter arrived bearing fronds of aloe. They must have seen half the work team glowing red with sunburn. A posse of school kids showed up one day, eager to help-frail boys of 9 or 10 carrying 20-pound rocks and buckets of concrete, staggering beneath the weight. Sri Lankans take tremendous pride in having guests in their homes, and invitations were extended to us by everyone we met, from tuk-tuk drivers to 8-year-old boys on the beach. One night Ranjith invited six of us over for dinner. It was a simple place, with concrete floors, cinder-block walls, and plastic patio chairs, but his wife cooked us our best meal in Sri Lanka. We began with a vegetable omelette, roti, and hoppers, a pancake-like dish usually eaten for breakfast. Then they ushered us into the dining room where they served us curried chicken, rice with cinnamon bark, fiery dal, and tuna baked in a clay oven. Sri Lankans don't eat with their guests - they wait until the visitors have gone home - so while we ploughed through 12 different dishes, Ranjith's wife and kids stayed in the kitchen, peering out occasionally to monitor our progress. By the end of two weeks in Galle, my team had dug foundations, built retaining walls, and laid bricks for two houses in Bataduwa. I was a little disappointed that we wouldn't have the satisfaction of seeing Chandana and his family move into their house, but I was consoled when I learned that we would witness the first handover of a Global Crossroad house, in a neighbourhood called Dadella. On the morning of the ceremony, my team was diverted to the Dadella site to help with the finishing touches. Thrilled to put her seeds to use, Caitlin designed a semicircular garden in front of the house, and planted it with cosmos, zinnias, sunflowers, and marigolds. The rest of us spent the morning clearing debris. As we heaped the garbage into a pile, my shovel scraped across a rolling pin, a tattered pillowcase, a tiny pair of blue pants. At 4 p.m., the family gathered in front of their new house, a simple cinder-block structure which had been painted a buttery yellow. A monk lit a tall brass oil lamp and chanted a blessing, and we were invited inside to admire the polished concrete floors and jackfruit-wood doors. It was the first of 100 houses that Global Crossroad planned to complete by the end of 2005; but only 26 have been built to date, and the company says it'll continue as long as there's interest from volunteers. Across the street from our celebration was a sea of bright blue refugee tents, a potent reminder of how much work remained. Before leaving Galle to travel to the north, I stopped by the Bataduwa worksite with a friend from my project team to say goodbye to the masons. A new brigade of volunteers was there, chopping at the soil with pickaxes and those ineffectual iron rods, guzzling water. Watching them work called up memories of my first day-the exhaustion, the feelings of ineptitude, the staggering heat. I lingered, repressing the urge to blurt out know-it-all tips. "I'm so glad I'm not them," I said to my friend as we climbed into a tuk-tuk, glancing over my shoulder one last time. We both knew it was a lie. |