|

observer |

|

|

|

|

|

OTHER LINKS |

|

|

|

Art reviewsTHEATRE'FLUKE': A psychedelic boat trip down a sea of ambiguity"Fluke," which ran at Performance Space 122 in April, reopened yesterday and continues through Jan. 28 at Collapsable Hole, 146 Metropolitan Avenue, at Berry Street, Williamsburg, Brooklyn; (718) 388-2251. Following are excerpts from Jason Zinoman's review, which appeared in The New York Times on April 29; the full text is here. Listen closely at "Fluke," a collage of enigmatic riffs on "Moby-Dick" presented by the rambunctious experimental company Radiohole, and you'll hear the gurgling sound of the deep. There's even a collection of electric fish flapping their fins on the cluttered stage. It has always been easier to like a show by this Brooklyn troupe than to understand it. But while past pieces have featured elaborate minispectacles or brief flourishes of chaos, "Fluke" is a more modest and meditative work, although what is being pondered is anyone's guess. There are a few snippets of oddball dialogue ("I've the need of needs. I'm going to get the score of scores") and a screaming punk rock song delivered by the always intense Eric Dyer, whose bald head and crooked features make him look like an overgrown and slightly sinister baby. At his sides are the alluring divas of Radiohole: Maggie Hoffman, wearing a pompadour and a glamorously bored expression, and Erin Douglass, whose corset interrupts an otherwise normal ? relatively ? look. There are of course a few avant-garde clich,s, like shining a spotlight in the audience's faces. But as with every Radiohole show, there are also some vivid theatrical ideas. Early on, each performer paints an eyeball on an eyelid, and they spend much of the show with their eyes closed. (They put on sunglasses when they need to see.) It's a nicely creepy effect, making them appear like cartoon characters or dolls whose eyes have popped out of their sockets. And by performing most of the show with their eyes closed ? no mean feat ? The stars of Radiohole show how easy it is to stage an ocean: all you need to do is to close your eyes and imagine. NYTimes**** FILM'The Cherry Orchard': Echoes of grief and loss modulated by humor

The teddy bear seemed an unpromising portent. Coddled in a junior armchair and bathed in a cool spotlight, the raggedy little creature sat at the front of the stage, looking self-consciously forlorn, as audience members took their seats at the Huntington Theater for Nicholas Martin's new production of "The Cherry Orchard" here. But fears that Mr. Martin's approach to Anton Chekhov's comic masterpiece would be soggy with sentiment proved happily unfounded. While this production, starring a softly radiant Kate Burton as the mercurial Madame Ranevskaya, does place a subtle emphasis on the tragedy in her past ? the death of her young son some five years before the play begins ? the teddy bear was a bit of a red herring, as it were. Mr. Martin's "Cherry Orchard," presented in a clean new adaptation by the playwright Richard Nelson, is brisk, unfussily funny and steeped in just enough emotion to give it a gloss of tender feeling without drowning it in teardrops. Ms. Burton, most recently seen in New York in Theresa Rebeck's "Water's Edge" and in W. Somerset Maugham's "Constant Wife," has an impressive Chekhovian curriculum vitae. She appeared in London as Olga in "Three Sisters," directed by Michael Blakemore and opposite Kristin Scott Thomas. (She has played all three of Chekhov's Moscow-hungering sisters during her career.) Ms. Burton has also appeared in a film version of "Uncle Vanya" and played Anya opposite Colleen Dewhurst's Ranevskaya in an earlier production of "The Cherry Orchard." But her most recent classical role on Broadway was Hedda Gabler, in a production also directed by Mr. Martin and seen at the Huntington before moving to New York. An actress of easygoing warmth, natural earthiness and bright comic instincts, Ms. Burton seemed an uneasy fit for Ibsen's darkly thwarted antiheroine. Shaping the role to suit her strengths, she and Mr. Martin uncovered unexpected ? and in my view untoward ? humorous underpinnings in Ibsen's tormented and tormenting Hedda. By contrast, Ms. Burton's natural assets are ideally suited to Ranevskaya, the flighty but endearing Russian aristocrat who comes home to her beloved country estate after years of scattered living in Europe, just in time to bid it a tender goodbye and lay to rest a few lingering ghosts, living and dead. Despite Ranevskaya's frequent recourse to tears ? generally accompanied by smiles, in any case ? "The Cherry Orchard" was emphatically denoted a comedy by Chekhov, who famously bridled at Stanislavsky's mournful premiere production for the Moscow Art Theater in 1904. Since then, directors have had to negotiate the distance among perceptions of the play as a heart-rending chronicle of loss or an indictment of an idle class or a comedy about the painful necessity of change. Although Mr. Martin's production is in a strictly naturalistic mode that derives at least superficially from the Stanislavsky model (the beautiful sets in a soft palette are by Ralph Funicello), he keeps the play's texture light, bright and active. Mr. Nelson's felicitous translation is stage-worthy and natural, with just a few jarring contemporary notes: Ranevskaya describes her feckless lover in a pop-psychy way as "thinking only of himself and his needs." In a program note, Mr. Nelson writes in a similar tone that in the play "Chekhov is bringing us through the stages of the grieving process with Ranevskaya." On paper that may sound reductive ? Chekhov as an artistic progenitor of Elisabeth K?bler-Ross ? but in performance it isn't. The idea gives Ms. Burton and Mr. Martin a lucid emotional entry into the play, and a result is a performance of transparent feeling from Ms. Burton that is neither stagy nor overwrought. In the second act her casual placing of a small bouquet of flowers on a grave ? presumably her son's ? flits by unheralded, for instance. Ms. Burton has a smile that can radiate any number of conflicting emotions, from simple joy to steely courage to trembling love, and she uses it beautifully throughout; this easy smile is the coin of a prodigal heart with nothing in the purse to draw on. The more somber notes are poignant, but unforced, as when, hard upon her entrance, Ranevskaya's eye falls with a queasy jolt on that abandoned teddy bear, and her face goes slack with renewed grief. In the second act, Ms. Burton's open-spirited Ranevskaya turns anxious and carping, as if in steeling her heart against the loss of the cherry orchard and the estate, she has closed it off to the field of human feeling around her, too. It's an intelligent, defensible choice, but it results in a constriction of the play's psychological texture, and Ms. Burton barges through at least one speech, Ranevskaya's upbraiding of the callow idealist Trofimov (a fine and feisty Enver Gjokaj), with too much scorn and not enough silken sympathy. NYTimes.com**** MUSICLe Villi: A musical case of the original willisHeard the one about the spurned maiden who became a vengeful ghost? If you have, it's probably through dance: the most famous form of the legend of the Willis is Adolphe Adam's ballet "Giselle." And while Giacomo Puccini's version, "Le Villi," is remembered as his first opera, it was actually conceived as an opera-ballo. So the Dicapo Opera Theater's decision to choreograph the work makes perfect sense. The piece is more a story set to music, with two-dimensional characters, than a compelling drama; dance is a good way to mitigate its stasis. And the Dicapo production, which opened on Friday, went a step further by pairing "Le Villi" with another early Puccini work, the so-called "Messa di Gloria" (or "Messa a Quattro Voci") from 1880. The idea was good, and the dancing was strong. Nilas Martins of the New York City Ballet, Dicapo's director of dance, has evidently elevated the company's dance standards to a degree disproportionate to its other abilities. His troupe, the Nilas Martins Dance Company, gave striking performances of choreography by Stephen Pier ("Messa di Gloria") and Mr. Martins himself ("Le Villi"). Saturday evening's only problem was one that has plagued many other well-conceived Dicapo productions: The performance of the opera just wasn't very good. It may seem mean to pick on a small company that does a lot with limited resources. But the "Messa di Gloria" showed that Dicapo is capable of achieving a higher standard. Admittedly the orchestra was weak, but the chorus sang strongly. And Mr. Pier's choreography reflected the bright, busy (sometimes cheesy) music in interesting ways. When the low voices intoned, "Qui tollis peccata mundi," he sent the male dancers across the front of the stage in Graham-like poses that were later embellished with the female dancers on a repeat when the women's voices joined in. The vocal soloists, however, were not a highlight. Arthur Shen forced a sizable tenor into tautness by over-singing; Oziel Garza-Ornelas similarly focused on pumping out sound. Mr. Garza-Ornelas visibly and audibly relaxed when, as the father of the heroine in "Le Villi," he had a character to portray. DANCE A dance fling to salute the soul man

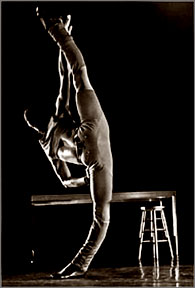

Dwight Rhoden's hip and slinky "Chapters" has Broadway dance musical written all over it. The balance of the program presented by the Complexions Contemporary Ballet on Tuesday night at the Joyce Theater was an up-and-down affair, with two of the most appealing dances coming from guest artists. But Mr. Rhoden, the company's chief choreographer and its founder with Desmond Richardson, has a promising thing going in "Chapters," which celebrates the music of Marvin Gaye. "Chapters" sets out to suggest the tightly intertwined lives and personalities of 15 friends, men and women in their 20s who have come to New York filled with dreams. Sounds familiar, but the story and the selection of nine songs are pretty much a pretext for an all-out dance fling that takes place in what looks like a bar. By the end, the recorded performances by Mr. Gaye start to feel unvaryingly loud and brash. The piece, seen here in a one-act form, needs more nuances and dynamic variation, both in the dance and in the choice of music, to become a full-evening work. The choreography could allude more to the song texts, particularly in Mr. Gaye's haunting antiwar "What's Going On." But the music's lazily insistent beat has the effect of a curl-relaxer on Mr. Rhoden's frizzy, hectic choreographic style. To watch these stretched, beautiful young bodies and sassy presences at easy play in the music is a great pleasure. And several of the fine dancers stand out from the crowd, among them Clifford Williams as a funny but lethal pal to all and Rubinald Pronk as a Village People motorcycle guy striding through on towering high heels. An expressive young powerhouse dancer named Bryan Arias is the runaway star of Mr. Rhoden's new "Hissy Fits," danced to Bach. The piece fully lives up to its name with a series of jousting duets for taut-bodied men and women with inexplicably snaking arms. An excerpt from Mr.Rhoden's 2005 "B. Sessions" gives Mr. Williams and Mr. Richardson a chance at more lyrical ballet-influenced movement, in a fine cast completed by Kimi Nikaidoh and Karah Abiog. "Loose Change," choreographed by the actor Taye Diggs, to music by David Ryan Harris, is a charmer. The solo gives the exquisite Mr.Richardson the chance to act and move simultaneously in an evocation of life's throwaway activities, useless but all-important. Matthew Prescott sets Juan Rodriguez and Yusha-Marie Sorzano to romantic spiraling about each other in "This Heart," a duet to music by Sinead O'Connor that adds a welcome tenderness to the evening. But Jodie Gates's new "Barely Silent" looks like outtakes from a Rhoden piece, with music by Alan Terricciano, performed live, and a murmured taped musing on a broken affair. NYTimes |