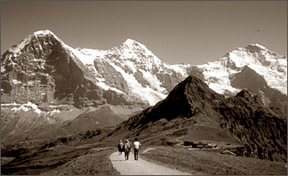

Only footprints here

Switzerland's efficient transport system can take a person virtually

every where ... except to one great mountain, says MAHESH VIJAPURKAR. Switzerland's efficient transport system can take a person virtually

every where ... except to one great mountain, says MAHESH VIJAPURKAR.

Walking back to the Alpine hut on the Matterhorn

SWITZERLAND is one of the world's favourite travel destinations. And

there are almost as many domestic tourists reaching every nook and

cranny of the country by a seamless transport system, its elements being

trains cogwheels, funiculars included cable cars, buses and trams.

It takes them to virtually every remote village, every mountain top

save one the Matterhorn, the snow-clad peak bordering France; the one

first climbed by Edward Whymper in 1865. It is a popular climb, even if

it means a three-day trudge guides cost a fortune and sometimes, the

climber, his life.

If there were to be a referendum, virtually every Swiss national

would vote against the very notion of a cable car "defiling the great

Matterhorn". So strong is the mountain's spell on them that at its foot,

the pride of place in Zermatt town has been assigned to the living icon

of mountaineering, 102-year-old Ulrich Inderbinen. If there were to be a referendum, virtually every Swiss national

would vote against the very notion of a cable car "defiling the great

Matterhorn". So strong is the mountain's spell on them that at its foot,

the pride of place in Zermatt town has been assigned to the living icon

of mountaineering, 102-year-old Ulrich Inderbinen.

Inderbinen has scaled the 4,478-metre high mountain several hundred

times as a guide, the last time being when he was 90. An image of the

man's face in relief is the town's way of paying tribute to him. The

town has also a large cemetery for young climbers who have lost their

lives.

It does not matter if there are only 2,000-odd beds in the smallish

Zermatt for the 1.7 million tourists who come for an overnight stay. It

does not matter if all of them go up in cable cars and rack railway up

the Gonergrat and other peaks to ski down the slopes. Nor does the fact

that a cable car route has been built to neighbouring Kleinmatterhorn.

During the season, there are as many as 300 people on the slopes of

Matterhorn, often courageous, enthusiastic and ill-equipped. This alpine

country has, by sheer use of technology, subdued every mountain.

The (humorous) selling line for travel companies worldwide who woo

visitors to Switzerland is: "we make mountaineering easy. We take you up

there in a cable car."

Train companies may skip Matterhorn but the system where if there is

90 per cent occupancy it is seen as overcrowding is continually

upgraded. Already, the system operated by 400 companies in remarkable

error-free co-ordination has made the country, albeit small, into a vast

metropolis.

The Swiss have undertaken a major project in magnetic levitation so

that trains, for instance, can run from Zurich to Geneva in one hour.

Work on a pilot line between Geneva and Lausanne has been conceptualised

and may become operational by 2020.

The idea is to have trains move at upto 500 kmph in partial vacuum,

the air being rarefied at 15,000 metres. These will carry passengers in

pressurised coaches. Once this Swissmetro project gets going, a new

revolution in train transport would have become a reality. To the Swiss,

"this is part of routine progress".

The Swiss may think the French may have made a mistake by replacing

trains with buses, because they worked on the trains, the buses, the

trams, the cable cars and even huge boats on the enormous lakes. For

instance, the time spent on a train is a delight, especially because it

is well run. Before it oiled the wheels of tourism, trains first

transported only freight.

Now, stations are served at the same minute every hour or half hour.

Trains and buses arrive shortly before, either the full or half hour,

and after establishing a vital link, depart. This makes for a shorter

travel time.

This has enabled Switzerland to be called the "railway country of

Europe" with 27,000 km of railway line (1,000 km is mountain railway.)

This enables a Swiss citizen to make 40 trips per year, the highest in

all Europe. And yet, he would prefer to trudge up the Matterhorn.

The system was developed way back in the 19th Century. Its advent

meant changes. Land growing cereals became grasslands, farming less-labour

intensive. But at the same time, the railways shaped the landscape and

tourism took hold.

The first rack railway was built in Rigi in 1873 and the one to

Jungfrau mountain in 1898. To another peak, Pilatus, it was to happen in

1889, dealing with a 480 per cent gradient, the steepest in the world.

Plush cabins came in as early as 1875.

But because most railways were built and operated by interests in

energy, the surplus electricity was used to electrify them because, even

after all buildings and squares were lit up, they still had more. The

country made a virtue of a necessity. |